A Form Of Optimism: Australian Critic of the Year James Ley

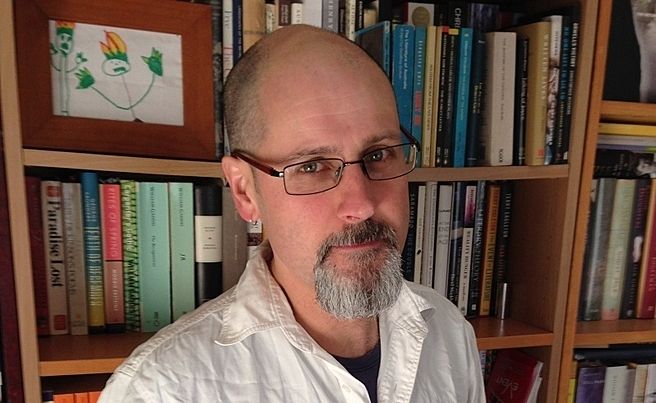

Critics were never quite adored, but they once commanded a certain respect. At the recent Melbourne Writers' Festival, Sydney Review of Books editor James Ley took Joe Nunweek through his history of half a dozen of the best, the public role of the critic, and how his publication is establishing itself in a midst of a rocky time for longform criticism.

Between 1779 and 1781, Samuel Johnson wrote a series of frank and unflinching biographies of 52 writers, Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets. It was probably the biggest critical project any individual had taken on up to that time, an undertaking that managed to be both authoritative and incisively human. Johnson's profiles made nuanced leaps in the philosophy of how we express ourselves with the written word while also addressing his subjects on a mortal, biographical level, all their frailties included.

It sealed his position as the most highly-regarded essayist of his century. Simultaneously, he was a joke - his ungainly appearance and nervous tics made him a figure of easy, cruel mockery. One contemporary poet invented a hulking, thinly-veiled figure called ‘Pomposo’. Later, William Blake would include the likeness of ‘Doctor Johnson’ in his menagerie of winged and twitching horrors. Even his future biographer, James Boswell, dwelt on his personal attributes in 1762: ‘a man of a most dreadful appearance’.

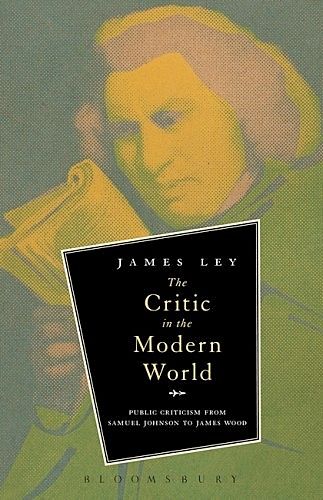

The lot of the critic: to be influential is not to get an easy ride. Even when you get a plaudit like Critic of the Year, which James Ley has twice. Sort of. In 2012, he was given Australia’s Pascall Prize for mere hours before contrite organisers mixed up their ‘Jameses’. This year, in the wake of his book, The Critic In The Modern World: Public Criticism from Samuel Johnson to James Wood, he was a shoe-in.

In person, Ley’s not as hardbitten as either of that collection’s bookends. He’s as measured and friendly to me as he will be a day later in front of several dozen Melbourne Writers Festival matinee-goers, some of which will ask harder questions than I. But in his writings as editor of the Sydney Review of Books, there’s a glint of steel. Picking up on a thread from Daniel Mendohlson recently about the etymology of idiot (“a true idiot, in other words, is ‘someone who acts in public as if they were still in private’”) he reflects on the way a proliferation of memoirs has become a proliferation of statuses and forum comments, the accumulation of collaged consumption that passes for a David Shields book. Casually, by-the-by, he says it: “We are living in an age of idiots, in the etymologically precise sense of the word.”

The Review, a website that publishes 6000 word comparative essays and won’t even grant its readers the indulgence of a Disqus plug-in at the end (“Letters to the editor are welcome”, however), feels like a bit of a last, proud bastion – the kind Australia’s poor cousin could benefit from. As Ley explains to me, the same crisis of space for literary criticism has been going on here in the lucky country, too.

“There was a sense that with the shrinkage of a lot of the traditional spaces for criticism – in particular, books pages were very constricted. There were a couple of quite bad months there where Australia lost the Australian Literary Review, which was a major supplement. Meanwhile, The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald and Canberra Times - all Fairfax titles – were essentially collapsing what were distinct books pages together. The number of voices was shrinking. That was the impetus.”

The ALR ended when Australia’s Group of Eight universities withdrew some $350,000 in annual support, so it’s ironic that the University of Western Sydney – impertinent at 25 years old, a scant 618th in the world rankings – has taken up the cudgel through their Writing and Society Research Centre while the more prestigious institutions were unfazed. “The idea is to actually allow critics to engage with the book at length and reconnect criticism to the art of the essay. To be able to write an essay-length review pays a greater respect to the work, gives the author a bit more of his or her due, and it allows critics to articulate certain things about that work that connect it to the wider culture. I think literature deserves that kind of indepth engagement.”

While Ley was thinking about what that sort of engagement has looked like and could look like – completing the PhD that would form the basis of The Critic in the Modern World and reading and writing hundreds of pages – he was trying to convey a sense of a book in hundreds of words. “A lot of the times I would have a book to review and you’d reading it and think ‘well, that’s a really interesting aspect, but I’ll never have a chance to address it. So that just gets left out. You have to cut to the chase.’ There is an art to that kind of concise reviewing, but it can be quite constraining and frustrating from a critical point of view.”

The Critic In The Modern World covers six writers and 250 years. Some of them, like Johnson, literally wrote dictionaries. Others, like T.S Eliot, often hastily adapted their lectures and talks into texts. But all went on at reasonable length, and it’s hard to think of anyone who habitually and comfortably writes to a broadsheet format about the arts and has been influential in the process since Christgau or Ebert’s heyday (and neither of them had to tackle books).

“I think there is something that’s happened recently that has something to do with the economics of it,” Ley argues. “Not just the economics of shrinking space in conventional outlets, but the kind of conflation of critical culture with commercial culture. There seems to be a kind of assumption, which I find a little bit troubling, that reviewing has something to do with selling. I think that has been blurred recently for a whole host of reasons.”

One, that I wrote about earlier this year, might be that both reviewer and publisher are pretty worried about having no role at all. Certain writers (probably you; definitely me) have gone into an assignment wondering about their precarious role at a publication with precarious ad sales, and considering a release by someone at a publisher or film distro or record label who also lies awake worrying about their job.

I’m glad to discover it’s something that the Sydney Review has taken a timely, vigilant stand on. UWS lecturer Ben Etherington has been penning a column called “Critic Watch” – last year, he clinically unpacked the logic of trade book publishing with respect to Hannah Kent’s bestselling Burial Rites: “In setting judgements of literary value against the enveloping background of contemporary marketing, I have sought to signal the importance of distinguishing the two. If good reviewers wish to ensure that this remains possible, diligence and faint praise may not be enough.”

“There’s nothing inherently evil about all this,” Ley continues, “but what it does is kind of blur that line between critical assessment and the promotion of the book. I think it’s something critics need to be very, very sensitive about. Perhaps more so now than any other time.”

But to read The Critic of the Modern World, every time is crucial. At either end, Samuel Johnson and James Wood are trying to construct a taxonomy of what’s working in literature and what isn’t in order to advance its cause: in between, William Hazlitt, Matthew Arnold, T.S Eliot, and Lionel Trilling are acutely aware of their context they write in. “Now” is threatened by authoritarians, anti-intellectuals, social disharmony – in Eliot’s case, by plebs who like sport on the train. It’s always of the essence.

What’s most engaging about many of the essays is the way Ley’s captured this, how in writing about the essayists he conjures up some of their nature – the matter-of-fact reading of Johnson’s strengths, contradictions and frailties emulates the subject's own poet essays, while the Arnold piece thrums with the tensions of the age that he thought an education in the best kinds of literature might reconcile.

It’s the Hazlitt chapter that stands out. Strident, iconoclastic and passionate, his essays brim with energy and a seething disappointment at the peers that let him down – Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey, who exchanged their febrile Romanticism for an establishment conservatism. “Deeply embroiled in the political and aesthetic debates of the day”, he also hustled like a modern-day freelancer.

“With his theatre criticism – he would go to the play, compose in his head what he going to say, and then write it out with the discipline of a journalist, overnight. That was necessary to get his copy in on time. But his prose was terrific.” One of his most famous pieces of writing, ‘The Fight’, may be the first long-form and descriptive pieces of sports journalism. Often, he seems more like a precursor to a good Grantland writer than a man of letters.

Today, Hazlitt is virtually out of print and out of the curriculum, but he shines through as Ley’s personal favourite. “Hazlitt was the first essay. I wrote that before there was the idea of the book, largely because Hazlitt was a favourite of mine. Then came the idea of building up the chronology, having critics from the past accumulate into different eras. A very selective overview, but an overview of that period of time.”

Apart from Hazlitt, Ley started with a list of 40 or 50 critics. “Once you have Hazlitt, Johnson seems a natural counterpart. They’re yin and yang, the last neo-classical and the great Romantic. And Wood is arguably the most famous literary critic of our time, so he’s a natural endpoint. When you look to the 19th century it has to be Arnold as the quintessential 19th century critic.

“Eliot was chosen because he was so influential in his day, but also because he was responding so directly to Arnold, co-opting his language along the way. That left that mid 20th-century spot, and Trilling was natural because he had written what’s considered the definitive biography of Arnold. So you get this pattern, this natural conversation between them as these later critics talk to and argue with that critics before them. So the structure basically informed itself.

Usefully, Ley’s book illustrates how the public role and responsibility of these critics waxes and wanes. Hazlitt may kick against the pricks until he dies forgotten at 52, but Arnold combined his zeal as an Inspector of Schools and an Oxford Professor of Poetry to shape modern Western curriculum, Eliot had audiences of nearly 14,000 turn out to hear him speak on ‘The Frontiers of Criticism’, and Trilling was a lynchpin in the New York Intellectual movement, seeking to locate his core interests within the history of “moral imagination”.

But now, the people who might have assumed these roles scrabble for academic toeholds and capsule review space. James Wood still has a soapbox, but to some commentators, it’s damningly limited, an abdication of the political dimensions of critique in favour of what William Deresiewicz has skewered as a “narrow aestheticism”. What to do?

“Wood writes about books without necessarily expanding that critique into some challenge or prescription for a broader social programme, unlike that school of New York intellectuals of whom Trilling was associated with,” Ley admits. “And there’s an interesting dynamic there. For someone like Trilling, writing mid-century, he could call on a certain authority by virtue of being a literary critic. It still had a kind of cache and intellectual heft to it. A lot of that came to be challenged in the latter decades of the 20th century, I think. We’re at the point where we can’t take it for granted that literature has some kind of special place. It’s one of many cultural expressions that can have claim on our attention, that can be complex and contain new ideas.

“The reason James Wood can’t and is so specifically a literary critic is that he has to build a kind of authority from the ground up again. To write about literature from within, he needs to write about to establish the mechanics about why it does, in fact matter – rather than assuming it does by dint of being literature. This is one of the reasons why Wood has been quite successful as a critic, but also one of the reasons why he’s been quite controversial.”

On top of his chosen confinements, Wood is also (yet another) white male, like the other five Ley chooses to survey. Elizabeth Hardwick, Virginia Woolf, and Susan Sontag all made his longlist, though his reasons for the final selection make sense. The day after our chat, MWF attendees will tenaciously make the same point a number of times – our critics have been and are homogenous, and in 2014, it’s impossible (not to mention gross) to picture a renaissance of criticism cast entirely in Wood’s image, or in the image of any of Ley’s subjects.

That’s doesn’t discount the book or his work, but it’s a fundamental challenge to 21st-century criticism. We want it to give literature and art the in-depth engagement it deserves, but the places where you get the tools to engage have a long history of excluding the people that should be writing about cultural expression, that have the most to say about the past and the present right now. And if they’re out of the picture, where does that leave the legitimacy of modern criticism to be about more than just “good books”, to cast its net wider?

In his chapter on Arnold, Ley quotes Trilling from his otherwise fond study of Arnold – “(his) criticism retires before the brutal questions of power”. And Ley notes that Trilling didn’t fare much better. “We talk of “culture” as if it’s meant to have this ameliorative property which may or may not be the case, but he never gets round to talking about what to do when confronted with a serious, tangible social issue.”

“With the critic, as with anyone else, it comes down to practice, rather than any justification. It comes down to whether you do so well enough, or make it intelligently enough. “ He pauses, stirs his drink a little pensively.

When the ALR went under, its outgoing editor explained their failed mission. They had wanted to create a much broader social, political and economic publication using the full intellectual resources of its writers, to move away from a pure engagement with the literary work. I can imagine what James Wood would say to that. And I think I know that William Hazlitt would say something different. With so many constraints but so many options, the Sydney Review could up being many things to many people.

“Maybe criticism is a good exercise for preparing for those bigger questions. “

James Ley's The Critic In The Modern World: Public Criticism from Samuel Johnson to James Wood is available from Bloomsbury Publishing now.