A Crazy Dream To Pursue: White Fungus For The Masses

From the comparative quiet backwaters of Taichung, Taiwan, New Zealanders Ron and Mark Hanson fought a valiant rearguard action to keep their art and culture magazine, 'White Fungus', in bloom. Stian Overdahl discovers how it's all finally paying off.

[caption id="attachment_8531" align="aligncenter" width="500"] White Fungus: Ron and Mark Hanson (L-R) photographed in Taichung City by Vivy Hsieh.[/caption]

As mainstream culture hurtles towards a state of constant distraction, with popularity gauged by Youtube hits, half-watched videos and likes and follows, the need for alternatives and antidotes grows stronger than ever. Enter White Fungus, a phenomenon that grew through the cracks - the magazine that either demands your total immersion or settles for your total ignorance.

Published from Taichung City in Taiwan by expat New Zealanders Ron and Mark Hanson, and now in its tenth year, White Fungus exists on the borderlands of publishing; indefinable, whether featuring an avant-garde composer, an essay on the origins of the dairy industry in New Zealand, or artists’ works in lush, full page spreads. Straddling multiple cultures – Taiwan, New Zealand, with an eye on art scenes further afield – the brothers have become practitioners of an alternate globalisation, linking art and music by aesthetic and political concerns, and identifying “localism in its most resistant forms”.

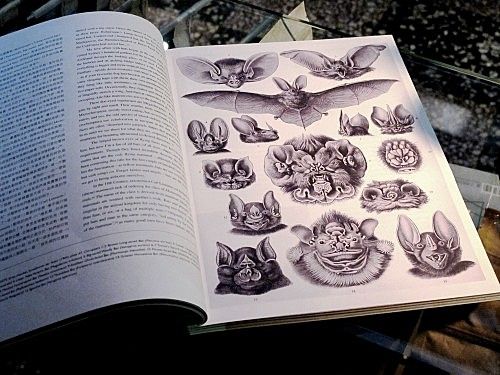

What does this mean in practice, if you’re one of the lucky ones who have been paying attention so far? The latest issue opens with ‘The First Woman on Mars’, an essay by American sci-fi writer Ron Drummond advocating the establishment of a base on Mars, populated initially by a single woman. The second piece is by Auckland art writer Tessa Laird, on her fascination with bats and plotting a redemption for the maligned mammals (its title: ‘In Praise of Bats, Our Exquisite Winged-Kin’). Both features are entertaining, look glorious, and at first blush don’t appear to have a great deal in common.

But since its inception, White Fungus has lived a double life overall. It exists on the periphery and ‘underground’, struggling for recognition in New Zealand, while simultaneously featuring interviews with major international artists, curating shows around the world – Auckland, Taipei, San Francisco and New York – and gaining the attention of major galleries and institutions. It is held in library collections and institutions including The Southbank Centre in London, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, the National Library of Australia and Te Papa.

That double life is now all but over – the magazine has signed a major distribution deal with circulation company WhiteCirc, which works with titles that include Dazed and Confused, Document and Lulu. It will see White Fungus distributed in more than 90 countries, in magazine retailers as well as in the niche art bookstores where it has traditionally been found. It’s a major result for Ron and Mark, and a win too for readers. The current 13th edition is being reprinted for a global launch, and an event in Berlin in February featuring performance artists from Taiwan will herald the new issue.

But what does it mean for a magazine that is resolutely anti-corporate, published almost advertisement-free for the last two issues, to suddenly bust on into the mainstream? Will the magazine need to be ‘watered down’ to be palatable - will it be sellling out? Long-time readers of the magazine can guess it’s an unlikely result, given its trenchant positions on politics and economics, its careful investigations of art and music. The brothers themselves say that it’s not their intention to undermine 10 years of hard work “just to sell a few pages of ads”, but both see it as a chance to reach a wider audience - to open up a new beachhead in the modern conflict being fought between corporate interests and individuals, between profit and integrity. “We want to re-contextualise some things going on in the mainstream, while bringing the underground to the surface,” explains Ron.

The opportunity to turn White Fungus and its off-shoots into a full time project is now tantalisingly close. That a magazine which started life as an art stunt protesting a road being built through central Wellingon could morph into a major concern ready to be consumed by the mainstream – while maintaining its critical outlook – is an unlikely chain of events. It’s been, says Ron, “a crazy dream to pursue”. And now, the brothers are chasing it.

I met with Ron and Mark in their home town of Taichung, a city of 2.6 million people in central Taiwan, where they work, teaching English to Taiwanese children and producing White Fungus. Some two and a half hours drive from the capital Taipei (or 50 minutes on the new high speed railway), Taichung is a city built from humble beginnings, with a recent history of rough gangs, poorly-lit streets and drunken moped drivers. Referred to as ‘cowboy country’ by expats for its lawlessness, the city has mellowed in recent years, benefitting from Taiwan’s economic modernisation and the links that have opened to mainland China. Property developers have done their work transforming the city, and the buildings along the brightly-lit main streets have the kitsch sparkle of new money, apartment towers with names like ‘Rich 19’ and ‘New York New York’. On the outskirts of the city are the sprawling industrial zones, responsible for the city’s prosperity, where vivid paddies of rice are dotted between the grey factories and warehouses.

It was late September and there was a definite sense that things were coming together. After a well-received 13th edition a deal for global distribution of the magazine had crystallised, from a London-based company; the European launch for the latest White Fungus had been finalised, with several Taiwanese artists to travel to Berlin in February 2014 for performances at NK Projekt. In Taichung, low pressure from a recent typhoon signalled the end of the summer’s oppressive heat, and Ron was counting down the days until he was out of his body brace, an exoskeleton wrapped around his upper body after a motorcycle accident earlier in the year (“Having a motorcycle accident is being prepared for death”, he commented later).

Both were in a mood to reflect on what has been a roller coaster ride for the magazine the past few years. The magazine was in hiatus in 2011, as they retooled and rested. There was a feeling that it couldn’t simply continue on – it needed either to break out, or to sink with dignity. They describe their 12th issue in the vernacular of American football as a Hail Mary pass, (the brothers have an American father), a giant throw into the opposition territory, hoping to connect with the wide receiver. It was a desperation measure when the clock was running out and there was a single play remaining. The result was a ‘dream issue’, with a new, larger sized format, that included a lengthy interview with artist Carolee Schneemann.

“Things kind of blew up for us in March 2012”, says Ron. That month, White Fungus was selected for the exhibition Millennium Magazines, a survey of artist publishing since 2000 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and also featured in UK magazine The Wire. “It was a double whammy that got things moving.”

Their profile has been boosted by shows and side projects, with a raucous launch event at P·P·O·W Gallery in New York for Issue 11, and Issue 13 launched in San Francisco at the Kadist Art Foundation. 2012 saw two new magazines, commissioned by galleries in New Zealand. The Subconscious Restaurant was commissioned by the Physics Room to accompany a series of noise and light performances in New Zealand by Taiwanese performance artist Wang Fujui, the tour itself organised by White Fungus.

Meanwhile, The Consumers of the Future, for Adam Art Gallery in Wellington, included a poster competition to accompany exhibitions of the Wellington Media Collective and Martha Rosler. With an artist’s statement beginning, “The contemporary era, we believe, can best be described as a state of full-blown publicity,” the large format magazine examined the ‘publicity culture’ of Wellington and the mayoralty of Kerry Prendergast, reaching back to the construction of an inner city motorway link in 2004-6. In doing so, it effectively reached back to the combative origins of White Fungus.

It was the threat of a planned motorway bypass that catalysed the Hanson brothers in 2004. The new road would run through an area of the central city rich with heritage buildings and populated by galleries and artists. As the council was preparing to rip the heart out of Cuba St with heavy machinery, its publicity apparatus was busily championing Wellington as the ‘creative capital’ of New Zealand, a jarring disjunct for the would-be creative capital being evicted. Attacking the plans for the motorway, and accusing Mayor Prendergast of vested interests, the first issue of White Fungus was printed on a photocopier, wrapped in Christmas paper and hurled anonymously through the doors of local businesses. The bypass construction eventually went ahead, but White Fungus had connected with its first audience.

While the magazine has increased in size and expanded its focus, its formative spirit remains intact. “We have morphed, and will continue to morph, but we don’t want to do it in an eclectic way. We still have a very strong identity,” says Ron. This continuity includes the commissioned historical essays that have kicked off each issue. Topics have included the backstabbing politics of Victorian zoology and their impact on the discovery and classification of the Moa bird in New Zealand. With many written by frequent contributor Dr Tim Bollinger, who has a PhD in history, they’re the kind of article you’d be perfectly happy showing to your grandmother, while also pointing to the magazine’s interest in engaging with history, dredging out the stories and subtexts which are frequently ignored or forgotten.

As the race to find original holiday destinations reaches its endgame for the world’s population of affluent, smart-phone wielding hipsters (decayed communist-era architecture in Bulgaria? Check. Nepalese wedding? Check. River boating in Honduras? Check), it may be that ‘going off grid’ now entails visiting or sojourning in destinations where no one had thought to go before, precisely because they sound a little boring. Taiwan seems to fit this shoe – a small island near China that nobody knows much about, except that it seems to have permanent beef with its mainland neighbour.

If little is known about Taiwan globally, that may be because since 1971 the country has had few international diplomatic relations, after the international community decided to recognise the mainland PRC as the official ‘China’ and threw the island into a state of political limbo. Taiwan now exists as a quasi-nation, competing at the Olympics under the banner Chinese-Taipei, but unable to join international organisations (including the UN). In 2003, when the SARS virus was sweeping Asia, since Taiwan is not a member of the WHO, the island was refused medical information. Finally, the organisation sent a single expert advisor, who promptly fell sick with the virus, was quarantined, and then sent home. The newspapers showed photos of him walking to the plane in a protective jumpsuit.

Ron first moved to Taichung City in 2000 to teach English, and younger brother Mark soon followed. Just out of high school, Mark worked at a supermarket in Wellington to save money for an air ticket. When he arrived, his wage as a teacher was nearly ten times higher than what he had been earning at the Thorndon New World.

As outsiders, the shock of living in Taichung was fertile creative ground. “Here, there are so many materials to work with,” says Ron. “When you’re in Wellington you’re not really surprised by your environment. There may come a day when it’s like that here, but for the time being we’re still constantly discovering things.”

The everyday can turn up surprising results. It was on an early shopping expedition in his new home that Mark discovered a can of white fungus on a supermarket shelf. Common in Chinese cooking – according to a food website, “White fungus is commonly used in soups cooked for soothing purposes like nourishing their bodies, healing dry coughs and clearing heat in the lungs” – a scanned copy of the can has appeared on the cover of every magazine, with colours varied according to the theme. Alongside each other the covers make up a Warhol-esque series of coloured prints.

On the cover, the can of tremella fuciformis has a twofold existence, ordinary (in the East) and unknown (in the West), gesturing to the two worlds the magazine inhabits. It comes at a critical time, when on the front lines of art, music and architecture there is growing recognition between East and West, a greater transference of ideas, cooperation and co-working. The brothers consciously see White Fungus as a chance to help develop bonds between New Zealand and Asia, between Taiwan and Asia, and the rest of the world.

In 2003 they returned to New Zealand, launching the magazine which found a growing audience at home, and was stocked by influential art bookstores overseas. Artist Tao Wells worked as the magazine’s publicist for a period, an episode that included a successful road trip across the North Island to find new stockists.

Ten issues were produced in New Zealand, but by the end the financial situation became dire. In 2009 they returned to Taichung, where they could earn a decent wage teaching English, vital if they were to continue to publish. Aside from the money, teaching overseas would be challenging and creative in a way that has no direct equivalent in the West. As we sat in the early evening talking about White Fungus, their lives as teachers percolated into our conversation – the problem students, the satisfaction of breakthrough moments, and the pressure from overbearing helicopter parents.

While the instinct for many would be to live in the larger, more cosmopolitan Taipei, they chose Taichung again. The weekends are spent in Taipei where there is a flourishing scene for experimental music and sound art, but an empty social calendar leaves them free during the week to concentrate on teaching and White Fungus. Isolation can be an excellent catalyst for productivity.

Still, Taichung is not without its attractions, including Z-Space, an artist-run exhibition space in an old indoor market, neighboured by a feminist bookstore and a brightly painted rest room as a permanent art installation. The city boasts numerous restaurants, night markets and the ubiquitous KTV. Sitting with Ron and Mark at a café in the indoor market near Z-Space, there’s certainly a sense of being far from the pitched intensity of a major city in the West. The café is named ‘Free Coffee’, apt since it had free coffee for several months after it first opened – no one seemed in a race to turn a profit. A nearby store sells reconditioned furniture, while another sells only board games. It’s a pace of life in which everything seems to almost float.

The prospects are for them to stay long term in Taiwan; the country is possessed by an energetic feeling, that now it is Taiwan’s turn, a sentiment boosted by a buoyant economy as the money flows in from China. Taipei is fast becoming a hotspot in Asia for experimental music and sound art.

“Ultimately I think the world is pretty fucked long-term, but I think we can have a bit of a run here,” says Ron. “No lessons learnt, but it’s Asia’s time to dominate capitalism.”

Perhaps the story of White Fungus offers an opportunity to reflect on ‘how far globalisation has come,’ the notion of a magazine that thrives on connectedness being produced in a city that isn’t far from being a cultural backwater. Or perhaps it’s merely the reality for the independent creative industries: increasingly located on the fringe, living and working where rent is cheap and there are less demands on time, broken up by occasional forays into the centres to network, visit shows and sell work. It’s not a bad guess, and oddly congruent with the birth of White Fungus, prompted by the brothers being turfed out of their studio in central Wellington to make way for progress.

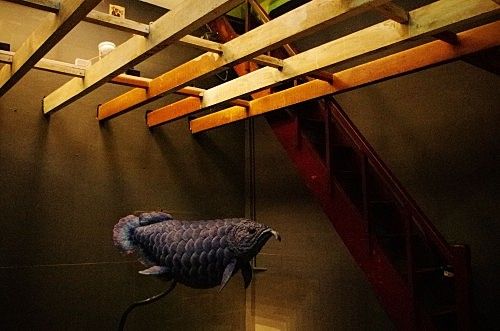

[caption id="attachment_8533" align="aligncenter" width="500"] A still from Chen Chieh–jen’s 2003 video work 'Factory'.[/caption]

In its adopted home, White Fungus has been active interviewing and writing about local artists, organising performances in Taipei, and curating events for Taiwanese artists overseas. A notable feature of the arts community is the availability of funding - money that makes it possible for artists to travel overseas, and contributes to White Fungus’s optimism they can continue to play a role in broadening links between artists in Taiwan and the rest of the world.

At a time when arts funding is harder to come by in the West, Taiwan’s largesse for the arts is a form of alternate diplomacy, a way to increase the country’s profile, while the usual channels stay blocked. My suggestion that the source of funding might influence the art being made is shot down by Mark, who says that since there is simply so little recognition for the country internationally, any artist will receive funding if their work gains traction overseas, irrespective of its ‘message’.

“It’s very different from New Zealand,” adds Ron, “Where the big artists tend to be ensconsed in the establishment. They’re pretty subservient to power. Whereas in our view the best visual artists here, like Chen Chieh–jen and Yao Jui-chung, are very political, and they challenge authority.”

Both Chen and Yao have featured extensively in White Fungus. Older and more established, their criticality is partly a result of engaging with Taiwan’s present situation in the context of its recent history, both having grown up and having been educated during the period of martial law. (Beginning in 1949 and ending in 1987, Taiwan’s period of martial law remains the longest in the planet’s history.)

Yao, who represented the country at the 1997 Venice Biennale, was part of a cohort who were taught at school that they needed to be prepared to retake mainland China. This was taken to a parodic extreme in 1997, when he visited the mainland to create the photo series Recovering Mainland China. He posed resplendent in full Taiwanese military regalia in front of a series of Chinese historical sites, a one-man army ready to carry out the national duty.

Meanwhile, Chen’s works often locate individuals facing obdurate and even perverse systems. His 2003 video work Factory documented the aftermath of major shifts by Taiwan’s economic machine. While once home to a flourishing factory-economy producing consumer goods, in the 1980 and ’90s most factories were closed as their owners moved production to mainland China in search of cheaper labour. In an abandoned garment factory Chen filmed a number of women returning to work seven years after the factory closed, encountering a world of dust and abandoned objects of the production line. The women, who were still unemployed and still owed unpaid pensions, were filmed working their old factory, the camera revealing a mix of stoicism and muted anger. The footage was interplayed with propaganda documentary film produced by the government in the 1960s when the industry was booming.

Taiwan now seems to be solidly in the grips of an international-style consumerism; Taipei boasts Little Tokyo, where teenagers can be found buying the latest Japanese fashions or beatboxing on street corners. This fasincation with newness has forced Yao to question whether the younger generation of artists can still use history to elucidate the present day situation.

“As for Taiwanese contemporary art under the sway of the internet and globalisation, I would agree that the young generation is indeed placing no effort to expand our knowledge of aesthetic and perceptual experience, and in doing so, is casting off the 'exalted' constructions of the previous generation. While most of this work is clever, ethereal and speaks of personal experience, this is not enough. If they cannot construct their pastiche of fragments on a fully elaborated genealogy of knowledge, then the superficiality of their project is likely to cause it to collapse.”

It’s a view that echoes with the focus of White Fungus, which, says Ron, chooses to interview or connect with artists whose work has distinct historical or political concerns.

“We look for work that is visually striking and concentrated but generally stay away from artists who have strictly aesthetic concerns,” explains Ron. “We believe research is the basis for strong work. There are so many institutionalized artists these days, which I compare to being like domesticated pets. It’s the artists who have taken a unique path that have the most interesting perspectives and stories to tell.”

While on paper Ron is editor and Mark art director, it’s largely a titular convention, glossing over the realities of a tight working relationship. “Generally speaking those have been the hats that we wear, but our working relationship has always been a very collaborative process,” says Mark. “It’s fluid”, adds Ron. “It comes out of conversation, and the whole point of White Fungus is that we discuss things, and it develops.” Later, when working on the interview transcript, it becomes hard to discern at times which of them is talking, the two melding into a single voice.

While any creative working relationship is going to produce friction, being brothers was also good training, if only because they’re less likely to take criticism personally. “I can say something and Mark will shoot it down and I don’t care,” says Ron. While in their younger years there was little connection between the two, as they grew older and the age difference diminished in importance, they found they had a lot in common. Mark says that a lack of ego has also been a big part of their successful working relationship. “If you have the same goal, every problem should be reconcilable. If you’re serving your own ego, and the other person is serving their own ego, then at some point it’s inevitable that you’re going to come to disagreement.” It’s a view that hasn’t always been shared by those they’ve tried to collaborate with, leading to problems.

For Ron, criticism is part of any conversation, a stance which he believes wasn’t well accepted in New Zealand while the magazine was based there. “In New Zealand we were really critical and went against the power structure, and that became difficult for us. If you go to Europe it’s acceptable to be really critical, to offer a frank assessment of things. But when you’re on a small island as New Zealand is, you just don’t say anything critical about anyone.”

In New Zealand the strength of White Fungus’ connections to galleries and institutions is something of a curate’s egg. Well-connected in Wellington, where it has its roots and good relations with galleries, in Auckland it has fewer links, and has no relationship with some of the larger institutions including the Auckland Art Gallery.

“They still ignore us. It’s quite stunning,” says Ron. “There’s so little discourse around New Zealand art and culture that anyone who brings anything to the table should be welcomed, whatever their persuasion. There’s so little that New Zealand can’t afford to say, ‘Well sorry we’re going to exclude you’, but it does.”

He believes there is an unwritten rule about cultural success in New Zealand. Overseas success is required before we will celebrate a local talent, as a kind of validation.

“New Zealand seems to have a skill for not recognizing local talent until it has proven itself overseas, a rule which applies equally to something underground like White Fungus as to a commercial act like Flight of the Conchords. New Zealanders don’t have confidence in their judgment, to say a thing is good or bad, they need that to be indicated for them, typically in London or New York. I don’t think it’s unique to New Zealand, many smaller countries are like that, and former colonies, but it’s something I’d like to challenge.”

White Fungus has interviewed prominent New Zealand artists, as well as casting a net further afield: those who left at an early age, such as composer Annea Lockwood; expats such as musician David Watson, who resides in New York; and those whose motions are less easy to summarise, including writer and filmmaker Chris Kraus. It’s a more diffuse conception of New Zealanders: of their place in the world, of the act of leaving or returning, and of maintaining a connection.

“New Zealand frustrates me more than anywhere else, but it also gives me a lot of satisfaction,” says Ron. “I think there’s a new generation, and it’s a chance to do things differently.

[caption id="attachment_8534" align="aligncenter" width="500"] A billboard advertisement for plastic surgery near the White Fungus offices in Taichung. Photo by Stian Overdahl.[/caption]

With a global distribution deal signed, there comes the danger of allowing a commercial element to creep in and disrupt the balance of White Fungus. In the past, it was easier to put principle before pragmatism.

“We rejected advertisements – I don’t know many magazines that rejected advertisers if they don’t look interesting enough,” says Mark. “We knew we weren’t going to make a lot of money off advertising, so it was more important to make a magazine you could still be proud of in ten years’ time.”

With a larger circulation they hope major international brands will be attracted to the magazine. Some ‘playing of the game’ is inevitable, and necessary to move the magazine into a space where they can fulfill its wider accomplishments, though they hope magazine sales will continue to be a major driver. But something will be lost, especially since the magazine originally had such a strong connection to Cuba St in Wellington.

“The ads aren’t going to have that personal, idiosyncratic quality they had in the early days, where it was almost like a dialogue,” says Ron. “[Wellington gallerist] Peter McLeavey started it, he would do his ads by hand, and they were almost like little art works, and then other galleries started playing around and experimenting,”

WF13 was also bilingual, with Chinese translations alongside the English texts, the culmination of a long practice of including Chinese text. This will have to be abandoned for the moment due to the practicalities of printing and distribution in Europe and America, while Ron says there’s the intention of launching a Chinese edition once the magazine is more established.

Even as some doors are closing, new ones are opening, and a heightened cultural profile opens up new opportunities for interviews and collaborations. “We’ve already covered a pretty broad range of artists so in terms of the future the expansion may be in other areas,” says Ron. “Our current issue has fashion for the first time. We’d like to include philosophy or political theory, but we’re also interested in making some mainstream interventions and communicating with some of the people in the mainstream we have an interest in.”

As I leave the White Fungus offices after spending two evenings with the brothers in Taichung, it’s almost 2am. A minor disagreement breaks out about a story book popular with the children – Mark wants it for teaching the next day, but Ron is adamant he needs it after one difficult student formed a particular attachment to the book. After a short discussion Mark agrees, and Ron’s pupil will get to enjoy the story about the bears. Despite their ambitions, there’s the sudden impression that no matter how popular White Fungus becomes, it’s going to be tough for them to tear themselves away from their teaching jobs.