A Brief History of Silo Theatre

Silo Theatre is renowned for it's slick, sexy, contemporary shows, but this wasn't always the case. We take a look back at the thirteen years Shane Bosher spent building the company from ground up.

Last week we kicked off our new video series with an oral history of The Mint Chicks. This week, we mark Shane Bosher’s retirement as artistic director at Silo Theatre by looking back at his time there and how, over the past thirteen years, he’s successfully built the company it now is from scratch.

A Brief History of Silo Theatre

Documentary

Curtis Vowell and Gareth Williams

Written Feature

Rosabel Tan

How to Not Fuck Up a Play: A Brief History of Silo Theatre

When Shane Bosher was offered the role of artistic director at Silo Theatre thirteen years ago, there was very little fanfare. It was a January morning and he was standing in the carpark of what is now the Basement – what was then the Silo – with a member of its trust board, Frances McCahon. She handed him the keys, looked at the venue, and gave him a single piece of advice: “Don’t fuck it up.”

And he hasn’t. “Well,” he laughs. “I don’t know.” It’s an early evening in February and we’re in a high-school gymnasium in Parnell, the makeshift rehearsal space for Angels in America. The two-part seven-hour epic will be Shane’s last production before he steps down, and it’s his most ambitious work yet. “We’ve had some really great days,” he says, “and we’ve had some really dark days. But that’s just the reality of dealing with the ebbs and flows of running an arts organisation in this country.”

He inherited the company during one of its lowest ebbs. Many people who were working in the industry then refer to it politely as ‘the dark ages’: After Sharyn Duncan launched Silo in 1998 – underneath what was then a porn theatre, what is now the Classic – she moved on to work at Bats in Wellington. It was 1999. The company fell into a period of sketchy management and the theatre landscape became dominated by a single figure, Auckland Theatre Company.

When Shane came on board he seized the opportunity to invest in an audience that wasn’t being catered to. “At the time, there was a lot of really great, edgy international work coming out that New Zealanders, for the most part, weren’t getting the opportunity to see.” He also knew there were hordes of ferociously talented actors coming out of drama school, and he wanted to give them a voice and a place onstage.

His early years saw him programming a lot of in-yer-face theatre, the movement of invigorating, brutal and unapologetic theatre that came out of the UK in the mid 90s. Aucklanders were exposed to the darkest human depravities and weaknesses: Mark Ravenhill’s Shopping and Fucking, Patrick Marber’s Closer and Sarah Kane’s Blasted. “We developed our name by eating dead babies to stay alive and raping people with kitchen forks.” Shane was young, 24, and had ideas about the kinds of risks he wanted to take.

Boys in the Band

Over those first few years, Silo established itself as a place where you could go to see slick contemporary works that would challenge, delight and disturb. Reflecting on those formative days, Shane notes that “while I thought I knew what I was doing when I started, I don’t necessarily think that I did.” He worked primarily on hunches back then, and they were proven right more often than not. “Luckily,” he adds, but it was luck grounded in an innate passion for what he was doing and an understanding of the industry. Before Silo had entered his vocabulary, he’d worked as an actor, a producer, a publicist and a barman (“Not a very good one,” he warns, “but there you go.”).

Still, he took risks back then that he knows he’d never take now. “I don’t think I’d necessarily consider doing Take Me Out,” he says. They staged the Tony Award-winning Richard Greenberg play – which chronicled the coming out of a popular baseball star – in 2006, with the full cast of eleven and an incredible locker-room set that included a row of working showers. It was a show that threatened to cripple the company. “I know far too much now about the financial implications and the scale of doing a piece of work like that. Whereas then, it was a cool play that I knew Craig Hall and Fasitua Amosa were going to be amazing in. So we had to programme it.”

To try and keep the company afloat, they programmed Roger Hall’s Glide Time. It was meant to be a kind of safety net, woven from the pockets of a more conservative, older generation. Devastatingly – though perhaps tellingly – Glide Time lost money, one of the only Roger Hall productions to have done so in the history of New Zealand theatre, while Take Me Out ended up turning a profit.

It’s experiences like these that has allowed for bolder, more calculated risks. Staging both parts of Angels in America is a testament to this and runs parallel with his own development as an artist and a practitioner. His tastes have changed. So have the kinds of risks he takes.

“I don’t think we’ve had a dead baby in a play for about thirteen years,” he laughs. “Certainly when I first started, I didn’t think I’d be framing a year’s season around the work of Caryl Churchill, Jaques Brel and Noel Coward. That certainly wasn’t how we first started. But I feel like it’s a maturing of myself as an artist, and of the audience, and of the company.”

He’s learned something with each play he’s put on. “Sometimes we’ve learned how not to fuck it up.” And how do you not fuck up a play? “The best way is to spend time choosing the right artists to engage with it. And then liberating them within the frame they exist in, but not settling as well. I think that’s one of the things that the artists we work with really love about the company – that we ask them to do the most extraordinary things. And the highest point is never high enough.” He talks to his actors about working towards the ‘look mummy, no hands!’ moment: where they’re simultaneously in control and not, driven by fearlessness and courage. “They’re doing things in the material and in the storytelling they didn’t know they could do.”

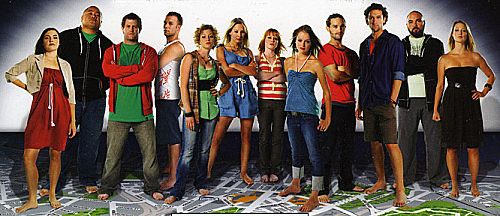

Creating a company that would support and develop actors was always one of Shane’s main intentions, and was seen most tangibly in their two iterations of the Ensemble Project in 2007 and 2009, which saw the professional debuts of 20 young actors. Working with Michael Hurst and Oliver Driver, each group devised an original show as well as working on a more classical text, and many of the actors who started here – including Morgana O’Reilly, Sophie Henderson, Sam Snedden and Dan Musgrove – have gone on to work intimately with the company.

It’s through initiatives like this that Silo has established itself as a middle-rung for emerging artists, and through vacating their old premises, they’ve allowed for an entry-level rung, Basement Theatre (so named as an homage to the original Basement, down at the Waterfront), to emerge. Together they’ve created a more cohesive – though by no means perfect – eco-system with clearer pathways to developing a career.

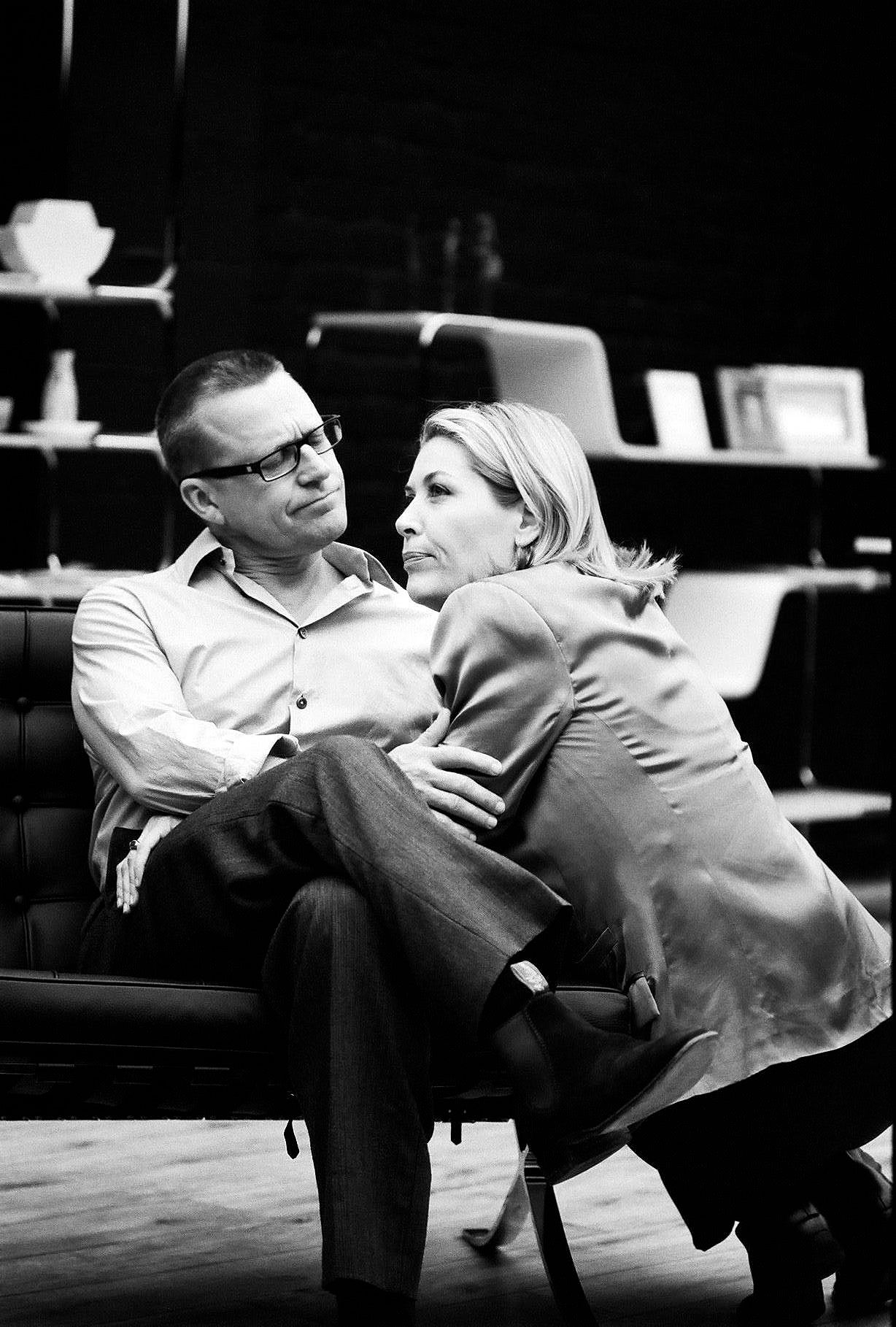

Silo hasn’t only been about developing emerging artists. In 2005 they staged The Goat or, Who is Sylvia: Notes Towards a Definition of Tragedy. It was one of the most potent productions Auckland will ever see. Directed by Oliver Driver and starring Jennifer Ward-Lealand and Michael Hurst, the play packed suffocating devastation into an under-ventilated theatre that seated only 105.

“It’s the most extraordinary experience I’ve ever had in a play,” says Hurst. “Ever. Where I was transported, as were the other actors, and as were the audience. Where at the end of it, everybody in that room had blood on their hands.”

The venue played a huge part in this. Frith Walker, the former General Manger of Silo, recalls Michael saying that the space didn’t allow you to fib. “In any other theatre,” she explains, “if you’ve lost your lines, you can get away with it.” But you couldn’t in that small space. “The audience was closer to you than you are to me right now, and there’s no lying to be done here.” It pushed him, and every actor who worked in that venue, to a whole new level. It pushed audiences, too.

“One night, Jennifer was wailing on the floor,” Michael recalls. The script direction asked her to howl three times: slowly, deliberately; a combination of rage and hurt. “So this particular night, she was there, howling. She did one howl, and of course I’m weeping.” He gestures to the space immediately in front of him. “The audience is this close.” He breathes in deeply, reclaiming the air around him. “The second howl, and she got to the end of that huge breath, and she went to take her breath in, and this woman leaned forward and put her hand on her,” he re-enacts it, “like that.”

“Even when I tell the story now I just start to cry because she just put her hand on her, like that. And nobody budged. Nobody even thought anything of it. And it was amazing.

Reflecting on the season, Hurst says: “It was a combination of a brilliant play, brilliant direction, all of us on our game, and the space being made available that way. It’s always tricky with theatre, because to pack that sort of punch you can’t do the numbers. You can’t do it in a 600-set venue. Well, you can, but it’s not the same punch. This was about being in a sweaty room and feeling really, really – what have we just seen?”

Even then, right at the beginning, Silo excelled at presenting a personality that was slick and sexy. “The interesting thing about the brand,” Shane says, “is that we created it through smoke and mirrors for a very long time and with very little resource.”

They relied heavily on the generosity of others: on favours from companies like Zambesi, who opened their wardrobes to them, and on talented professionals who were willing to donate their time, simply because they believed in what Silo was doing. “People like John Verryt and Rachael Walker and Elizabeth Whiting and Jeremy Fern just going: ‘Yes, we will create a world with whatever environment we’re given to realise the story, even if we’re being given $1.50.”

Professional theatre values were always core to Silo’s ethos. “Couldn’t have a wobbly set,” recites Frith. “Couldn’t have a prop that was about to fall apart. Couldn’t have a loose thread. Couldn’t have anything that looked cheap.” It was also about great work. “Plays that are brave… we’d failed if people left the theatre going, ‘Where’s the car?’ We wanted people to leave saying, ‘I hated that’, or ‘I loved it, or something but for godsake, feel something.”

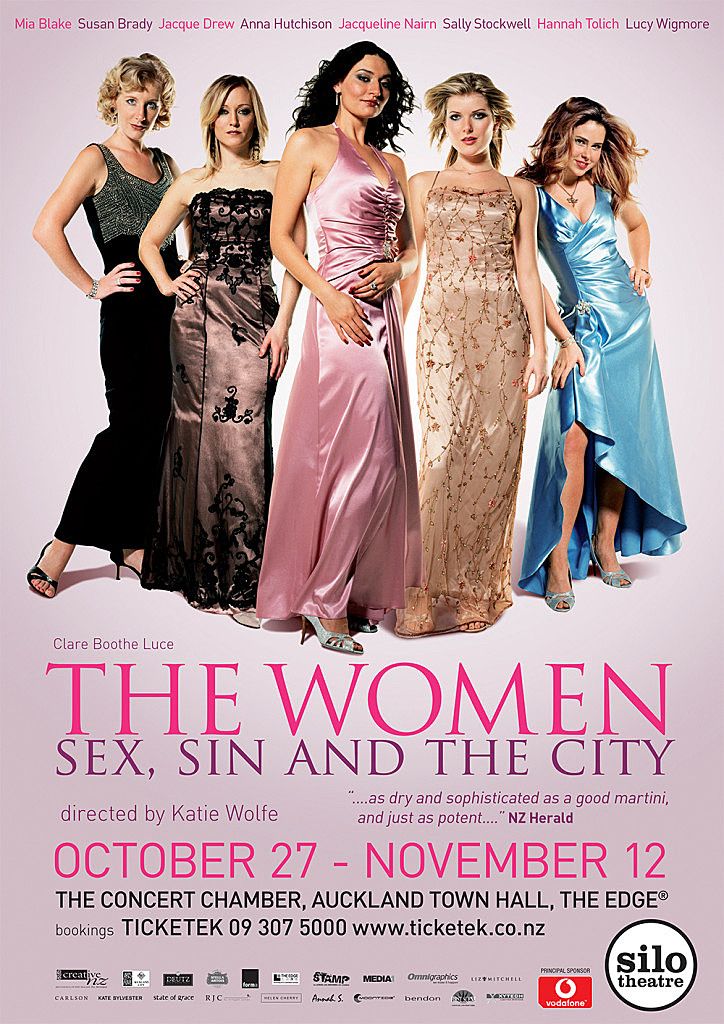

It was this drive to constantly push themselves, both in terms of performance and design elements, which made their 2004 show, The Women, a success – a significant one, that saw the company shifting gear after that. “Even with our tiny little budget,” exclaims Katie Wolfe, for whom The Women was her theatrical directing debut, “I think we had $2,000 for an eight-cast play – we were able to take those ideals and put them into a shape.”

The play’s six-week season completely sold out and had to be extended twice. Later, it toured to Downstage theatre in Wellington and back again to Auckland where it played in the Concert Chamber. “We had no idea that The Women would be the success that it was,” recalls Katie. “There we were, staple-gunning carpet to the roof the night before. I’d pulled in a favour with Sara Beale, who did the amazing costume design on it, and bang – there it went. It was there.”

“It happened very quickly,” Katie says of Silo’s brand. “It wasn’t like it developed. Shane walked in and went: this is what I believe in. Great writing. Great design meets great performance, and bang, it was there. It just worked.” She also cites Shane’s ability to attract experienced practitioners. “You had people like Michael and Jennifer coming back to the ghetto because they recognised there was really good work going on there.”

The generosity of those in the industry is something Frith mentions, too. “There were always massive giants of the theatre community shouldering it. And this young, enthusiastic energy shouldering it as well.” She feels, too, that in some ways, those budget constraints created greater freedoms. “I think sometimes having no money makes you braver. It makes you work harder. It makes you do things in a better way. Sometimes the money is a luxury that almost gets in the way of making braver choices.”

I ask Shane if he feels that theatre, and the way that Silo theatre is managed, is a sustainable model. “The creation of all art is risky,” he says finally, carefully. “I think we’ve been very lucky, in that to a certain extent we’ve been working with established product and very artistically capable artists. Certainly when you invest in new work and new activity it doesn’t always work out.” He explains that whenever he selects a portfolio of programming he always tries to balance riskier propositions with pieces of work that he knows an artist or an audience are going to respond to. That’s how they’ve remained sustainable.

“If we take a risk with an artist,” he says, “in terms of selecting a piece of work to develop them, we’re doing that very consciously and if that project loses money, that to a certain extent is okay, as long as we’ve got enough money to absorb that blow, as long as the development and the process has actually enabled that artist to learn and grow and shift and change.”

Over the years, the infrequent programming of New Zealand works has come up a number of times. It’s one of the main criticisms levied against Silo, and something that could be seen to stem from a reluctance to take a different kind of risk. Katie Wolfe suggests this wasn’t a deliberate tactic. “There were so many New Zealand projects he wanted to put on,” she argues, “but [Creative New Zealand] chose not to fund them.”

“I don’t know why some of those applications were declined,” Shane says when I ask him about it. “We tried twice to commission Toa Fraser to create a new show for us, and unfortunately that was never realised. There were other projects that didn’t work out, too. Commissions that are still in stasis, that were never completed to a standard that they were happy with.

It’s something that Sophie Roberts, the new artistic director of Silo Theatre, plans to address. They’ve already got a new commission in the works. “I’d really like to establish more opportunity for original new work to be made with the company over long periods of time.” When we talk, it’s a week before she steps into her new role and she seems cautious about making any promises, but speaks broadly about what she’d like to achieve: “Stuff gets made so quickly in this country. I’d really love to be able to nurture groups of artists to create really ambitious pieces of work over long periods of time.”

Sophie and Shane also share the same concerns about the future of theatre in Auckland, particularly in terms of supporting the development of theatre-makers in the city. “My biggest concern,” says Shane, “is that there’s not enough resources in place to take the high-potential artists that are emerging and really pick them up and move them into proper professional careers. There’s not enough money for everybody. And I worry that because there’s so much work, a lot of artists that are really great may fall by the wayside because they’re not noticed.”

He pauses. “There’s a lot of really great work, but there’s a lot of bullshit, too. And there’s some work that I kind of go: This. We’re better than this. A lot of work gets executed in a lo-fi frame and lo-fi can actually become an excuse for laziness. And I worry that actually we’re moving back to a time where all those different facets of theatre production which create a great piece of work are being forgotten and we’re ending up with actors – some really good – just mucking around.”

Despite these complaints, his decision to leave Silo didn’t stem from any disillusionment with the industry. The opposite, in fact: he’d started feeling like he was stagnating and was craving new opportunities. “Sometimes you gotta stab the baby.” Once he leaves, he’ll be directing Jumpy at Fortune in Dunedin, working on a couple of cabaret shows, helping take Morgana O’Reilly’s one-woman play The Height of the Eiffel Tower to the Edinburgh Fringe and working on two new shows “which are at very embryonic stages, which I’m going to spend the last couple months of the year beginning to push into life.” He feels nostalgic about leaving, but acknowledges that Silo has always been about championing the next conversation. “I feel like I’m getting a little bit long in the tooth to be able to champion some of those ideas and some of those new movements, so I think it’s a really healthy opportunity for the company to transform into the future.” He’s excited about passing the baton onto Sophie Roberts. “While we’re likeminded in certain ways, she’s very much her own artist and she’ll take the company and drag it kicking and screaming into the future. I feel that’s a great thing.”

“Companies evolve because of the fearlessness of their leaders. And she is, to me, a fearless artist. She will shift and change and develop in extraordinary ways if she continues to be fearless, and ferocious, and as talented as she is.”

http://pantograph-punch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/52134_777259308980646_2632954060672803623_o-500x333.jpg

Two weeks into the season of Angels, Shane’s back on Ponsonby Road in the Silo office, trying to pack up the last thirteen years of his life. Given he reads at least 300 plays a year (“some of those, look, let’s be honest, it’s not to the end”) there’s a lot to pack.

He seems tired, but calmer than when I saw him mid-rehearsals. “Getting the show up was possibly the most challenged I’ve ever been,” he confides. “I don’t normally lose my shit, but I had a few tanties. I had a few tears. And I had a few panic attacks and I had a whole lot of carry-on that I’m normally pretty good about pulling in line.” Part of it was the pressure of it being his last show. Part of it was the demands that naturally accompany a show like Angels, not only in terms of performance but the design elements, too. It’s an endurance event. And for the first time in years, they didn’t go through their standard process of doing a technical dress run, two dress rehearsals and a preview. Their first dress rehearsal was opening night. “But it’s gone really well,” he says, “and I’m pleased with the result.”

Sophie’s wandering around the offices too – she’s set herself up temporarily in their meeting room – and already seems at home in the space. It’s a transition that feels like it’ll almost be seamless. Different, but still grounded in a shared understanding of what Silo theatre represents. She defines it like this: “You’re seeing actors working at the absolute ceiling of their capacity. You’re seeing bold design. You’re seeing work that’s always reaching for something.” It’s theatre that asks big questions. “That always feels – no matter what the show is – like people are reaching for something bigger, and more complicated.”

Before I leave, and before he does too, I ask Shane if he’s got any last words. “I’ll probably turn to Sophie and Jess [Smith] and Tim [Blake] and Helen [Sheehan] and say: Don’t fuck it up.” He grins. “But beyond that," he says, "it’s theirs to do with as they wish.”

Correction: An earlier version of this piece stated that Sharyn Duncan went on to "launch" Bats Theatre. Bats was launched in 1989 by Simon Bennett and Simon Elson. This has now been amended to avoid confusion.