Faith and Feeling in A Boy Called Piano

Tulia Thompson goes behind the scenes of Nina Nawalowalo's directorial debut in film, 'A Boy Called Piano: The Story of Fa’amoana John Luafutu',

and the mana and trust necessary when working with stories of trauma.

Tiny bubbles of air rush and flow, eddying against the darkness. Slowly, a young Pacific boy appears. He is submerged underwater, smiling peacefully. I think of my own homeland, Fiji, but also the womb. Slow piano music plays.

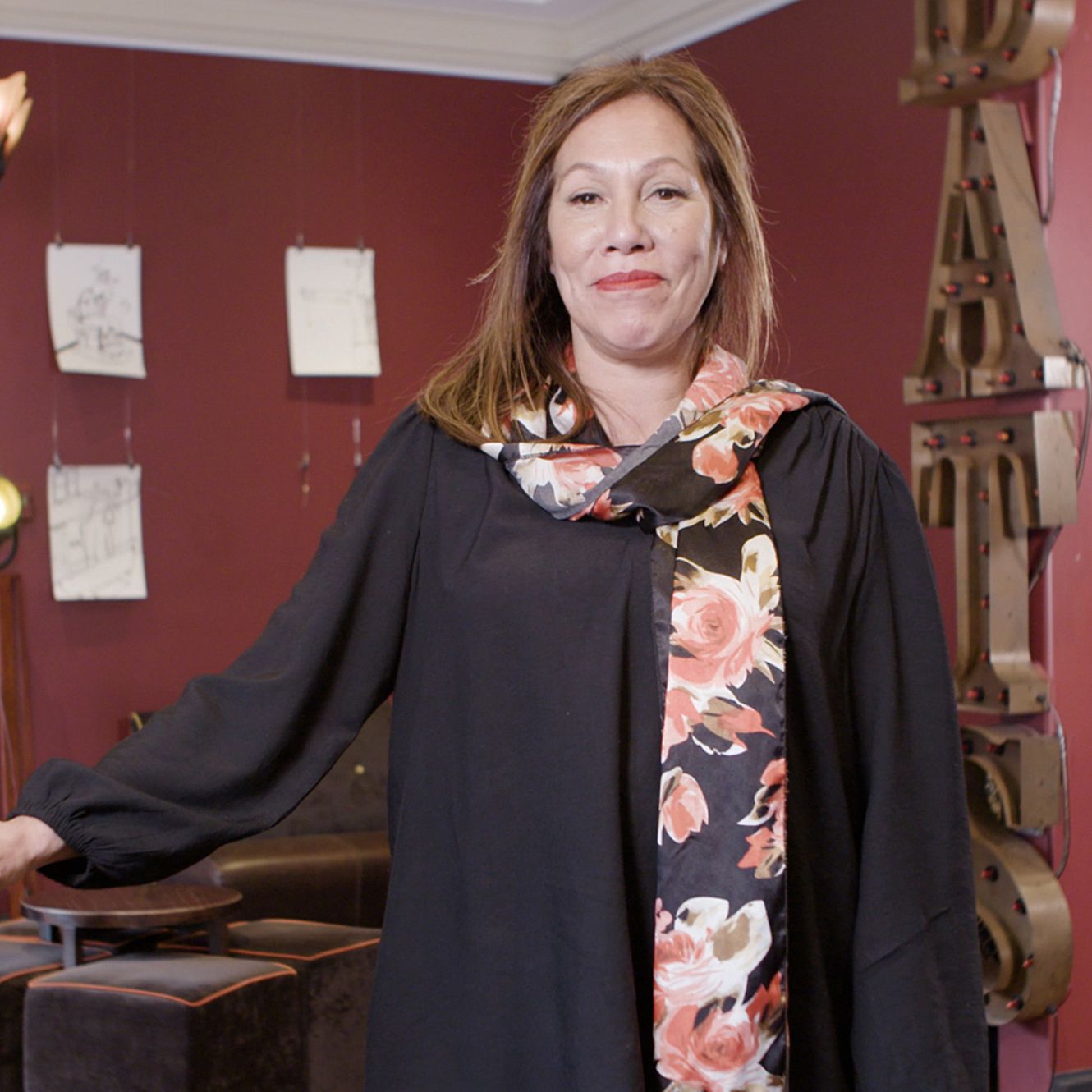

“I wanted to capture things that trigger memory,” says first-time director Nina Nawalowalo, a theatre-making stalwart whose directorial debut A Boy Called Piano – The Story of Fa‘amoana John Luafutu premieres at the New Zealand International Film Festival this August. The feature documentary tells the story of Luafutu’s abuse in state care in the 1960s, first at Ōwairaka Boys’ Home in Auckland, then at Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre in Levin. It draws on the play Luafutu co-wrote with theatre-maker Tom McCrory, A Boy Called Piano, alongside interviews with Luafutu and his aiga, and footage from the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in State Care. Luafutu’s son, actor Matthias Luafutu, appears prominently.

For Nawalowalo, water signals freedom, “what freedom is to children.” It conveys the profound loss of the natural world, for children and young people that are incarcerated.

“One of the things that gets taken away when you’re in a cell, is nature. You can’t feel the wind, you can’t feel the ocean, you can’t feel the natural environment. For Indigenous people and Pacific people, that is our soul. And everything of who we are,” says Nawalowalo.

There’s a scene where Luafutu, originally from the villages of Satalo and Poutasi, Falelili, Sāmoa, is standing beside a turn in a river, underneath a steel bridge. He wears a black puffer jacket and black cap. He is surrounded by dark green, angular forest. You can hear the birds and insects. He explains that he was one of many young people who planted the pine forest, while he was a teenager at Kohitere. You can’t watch the scene and not be horrified to hear that teenage boys were subjected to hard, physical labour. He kneels down and flicks the flowing water over his bare, tattooed arms. You can see the multi-coloured river stones though the clear water.

Still of Tane in water, courtesy of NZIFF.

Nawalowalo is a powerful storyteller with a 35-year history in theatre, including with her leading Pacific theatre company The Conch. Her plays Vula and Masi have a distinctly Fijian lens, and were influenced by a return to Kadavu, Fiji, when her father was seriously ill. The return home was a turning point. It triggered a profound realisation that she needed to reflect who she was, and use Fijian culture and imagery in her plays. In Kadavu she fished with women in the lagoon – she would later replicate the lagoon in water that covered the stage in Vula. It was also a way of honouring her father. She says that loss continues to be woven throughout her creative works. “I think everything I do is somehow linked to loss. Or loss of memory of things.”

While shifting from directing theatre to directing a film for the first time was challenging, Nawalowalo enjoyed the collaborative process, and was supported by a strong team of creatives, including her DOP, Jess Charlton. Nawalowalo loved the delicacy of Charlton’s framing and composition. Her vision for the film was enhanced through the music by Mark Vanilau, who was Dave Dobbyn’s pianist for 16 years. “There's a spiritual element every time he puts his hands on the keys,” says Nawalowalo.

As a producer with three young children, Katherine Wyeth says it was great to work with Nawalowalo, who is similarly focused on wellbeing and family. Nawalowalo welcomed creative input, but also kept her early creative workings private. “She’s very collaborative, and the process can be quite mysterious. Little by little, her vision would be revealed, but she’s quite protective over those early stages,” says Wyeth.

While Nawalowalo was protective of her creative process, she knew through experience the importance of being true to her own vision. “I thought if nobody likes it, it doesn’t matter. At least I’ve tried to do it my way, rather than copy the way documentaries are always made.”

Image of Director Nina Nawalowalo, courtesy of NZIFF.

But how do you go about telling a story like Luafutu’s, a story of intense trauma at the hands of an indifferent state? How do you sufficiently honour the person and aiga at its heart? And how do you tell the story in a way that people come away calling for change?

Nawalowalo pauses.

“It’s deep trust always, isn’t it?”

Nawalowalo and Luafutu have worked together now for more than eight years. Nawalowalo’s husband, actor Tom McCrory, found Luafutu’s first book, A Boy Called Broke, in his pigeonhole at Toi Whakaari Drama School. It had been left there by Luafutu’s son Matthias, who was one of McCrory’s students at the time. Matthias was leaving Toi Whakaari, and left the book as a gift. Both Nawalowalo and McCrory were moved by the story, and they approached Matthias about turning it into a one-man-play that he could perform. They wanted to bring more of Matthias’s life into his dad’s story, and “it opened up into a generational story. It’s his dad’s book, but what about bringing that story into the now?” explains Nawalowalo.

The play that emerged was The White Guitar, written by Luafutu and his sons Matthias and Malo. It had sell-out seasons and an eight-city tour in 2015. After that, there was more to be told. Luafutu’s play A Boy called Piano emerged because Nawalowalo and McCrory both wanted to go deeper into Luafutu’s experience of institutional abuse. The play had a development season at BATS Theatre in 2019; however, Covid-19 lockdowns prevented a national tour. Adapting it as a feature documentary was a way of getting Luafutu’s story in front of a broader audience.

Still of Fa'amoana John Luafutu, courtesy of NZIFF.

Creativity bursts from the same sites as despair. There’s a profound moment in the film when Luafutu and Matthias are standing outside the razor-wire fence that surrounds Pāremoremo prison. Matthias reflects on the times he would visit his dad there, eventually ending up there himself. Acting has been the healing journey away from that life. His own son, Tane, has followed his path into acting.

“They’re a family and we’re a family as well,” says Nawalowalo. “Opening up and exploring one’s personal stories means there must be a lot of trust across all parties. It was important for Fa‘amoana to feel that we could represent and tell the story in the right way.”

This meant both making sure that Luafutu and his aiga were comfortable with what material was told and collaborating closely about content. Nawalowalo would come up with ideas – often expressed as images rather than text – and ask him what he thought and felt about it. The talanoa was significant, as was learning not to make assumptions.

“It’s delicate. Everything is built on trust. You have to be selective, with how you tell a story or what you reveal, because nobody in this world is perfect, and no family is perfect.”

As a child, Luafutu was subjected to ongoing abuse by people in positions of power who should have protected him. It is remarkable that he has been able to trust anyone, let alone a director to tell his story. He explains that Nawalowalo has a “patient, loving, careful style of working, that brings out the best in everyone.” His trust in her was not just about their long-spanning relationship, but also about the Pacific lens that she brought to the story. “To me it is like the fāgogo, Sāmoan stories, my great grandmother told to me as a child in Sāmoa.”

He loves her use of beautiful imagery, and insight into the role of the women in the aiga. “In a story about men, she highlights the importance of the women; the mothers holding families together,” he says.

In terms of men, Nawalowalo was conscious of the history of racism in Aotearoa, and how Pacific men have been represented in film and media. She was aware of how people speak about gangs without real knowledge or insight into the driving forces that put Pacific men into them. In the case of Luafutu and his friends who were gang connected, it was their deep friendships that helped them survive. “All of these things are great strengths that bonded children together, because they went through these very dark times inside a state system, and those unbreakable bonds are amazing things, actually, but they can be represented in different ways,” she says.

It was important to Nawalowalo that the film-making process be mana enhancing rather than diminishing.

Think of racist representations of Pacific men, such as in Police 10/7. The point of difference with this representation is that it involves a survivor taking control of his narrative. “Fa‘amoana speaking from his own truth, directly to people, is very unique. And it's unfiltered,” she says.

Nawalowalo extended her desire for mana-enhancing representation into the look and feel of the film, layering in the visual aesthetics that are important to her within theatre-making, and keeping the feel and sensual experience of her theatre pieces within film.

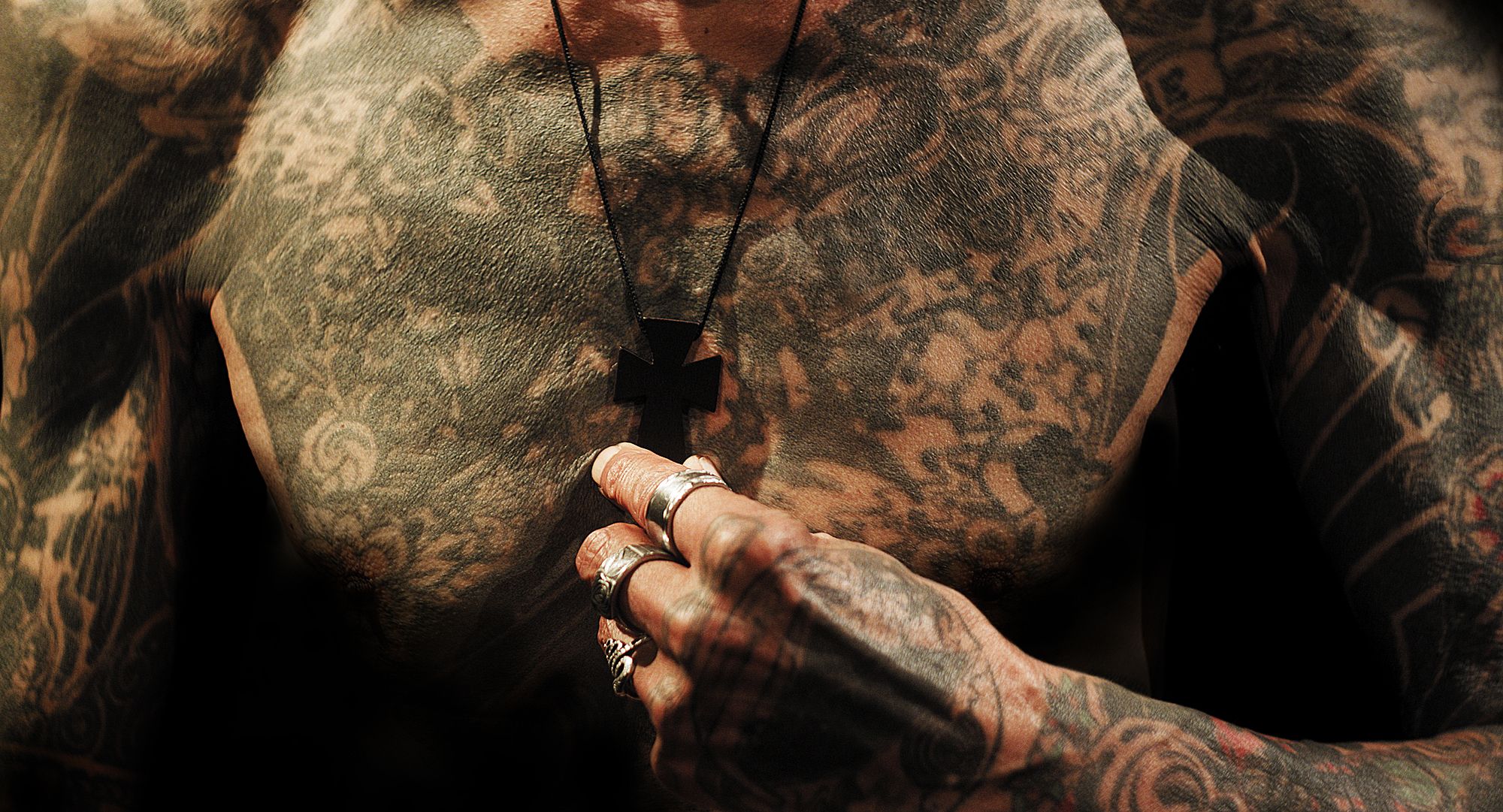

She worked with colour grader Gareth Evans to make the skin tones look beautiful, “[trying] to make the colouring really rich. You are looking at things of darkness, or that are supposed to be negative, but are actually making it look beautiful. It can disarm an audience because they can look at something like a tattoo that sometimes the media can represent as negative. Actually, it's beautiful. It's the strength and the beauty of that.”

Promotional image for 'A Boy Called Piano', courtesy of NZIFF.

When theatre company The Conch started working with Fa‘amoana John Luafutu in 2018, “There was complete denial from the New Zealand Government that the atrocities had even occurred,” says Wyeth.

Now, the Royal Commission of Inquiry has led to many survivors stepping forward. Wyeth is excited about the opportunities for survivors to see the documentary during its six NZIFF screenings throughout the country. “Fa‘amoana using the power of his amazing creative voice to tell his story has led to such massive change.”

Luafutu is clear that we as a country need to face the harm done, as:

“healing is not something just personal, this country needs to face the truth of its history to heal. To do this we’ve all got to be creative, and create solutions which bring change. I believe the truth will set us free.”

Filming A Boy Called Piano meant that Nawalowalo had to return with Luafutu to Kohitere, where he was detained 55 years earlier. “Why would I ask him to do that? Why would one ask a man to revisit some of the darkest things in their life? Because we must take control of these things. By revisiting something, you can release it, and you can say, ‘You don't have that power over me’.”

It was vital that Nawalowalo followed Luafutu’s lead. She would adjust what they filmed based on whether he felt okay. It was still a risk, however. “I don't think he even knew emotionally how he might feel,” says Nawalowalo.

For Luafutu, the gym and the security block were sites of trauma. The gym was one of the very violent places, where the screws would turn away and “the kids would battle it out”. Nawalowalo held off filming in those places until towards the end. “We knew it was a place of darkness,” she says.

The need to face that darkness is mirrored by Luafutu’s own process of writing and healing. “When people think of healing they think of easing pain, but the reality is to release it, you’ve first got to feel it,” says Luafutu. “In writing A Boy called Piano, I had to go back to experiences I’d suppressed for years. I had to go into the darkness, as Nina says, to find the light. Even if it’s just a fine pinprick, you follow that thread and it leads you out.”

A Boy Called Piano: The Story of Fa‘amoana John Luafutu

Whānau Mārama New Zealand International Film Festival

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

3 and 4 August

Ōtautahi Christchurch

7 August

Te Whanganui-a-Tara

9 and 10 August

Ōtepoti Dunedin

14 and 17 August