The Sea is My Mother

What poet David Eggleton wanted to know was, what was New Zealand culture anyway? Now Poet Laureate, David reflects on his legacy, and writing anti-poetry.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Noa‘ia ‘e mauri. The sea is my mother. I was born in a double-hulled canoe during a storm. From her, the sea, I received my life source. Now the seaweed grows in her floating hair. Alalum. Fa‘iakse‘ea. On my mother's side, I come from an ocean people. My Rotuman grandfather, my ma‘piag fa, Tonu Sitiveni, was a canoe maker, a carpenter, a boat builder from the village of Motusa. My grandmother, Usenia, my kui fefine, was from Ma‘ufanga, near Nuku‘alofa in Tonga. She swam and dived and sailed between the islands of Tonga and Rotuma and Fiji. Eventually she went to live in Levuka on Ovalau, Fiji, overlooking the sea. Usenia had twelve children, and my mother was her youngest. My father was an airman, orphaned young, who fell from the sky at Lauthala Bay on Viti Levu and was nursed back to good health by my mother.

When I dig down into my early sense of identity, I find colonial relics made of fine white mats, braided sennit, tapa cloth, starched khaki uniforms and brass buttons. Fiji in my childhood was a fantastical place, a British Crown colony in the years before it gained independence from Britain in 1970. It truly was a melting-pot culture: Fijians (the iTaukei, people of the land), Rotumans, Tongans, Indians – Hindu, Sikh, Muslim – Chinese, as well as Europeans and part-Europeans. (Rotuman people are of Polynesian ethnicity; the remote island of Rotuma was ceded to the British to become part of the Fiji Islands in 1881.)

Even as a child I was aware there was a strong sense of the carnivalesque about everyday life: a tropical hubbub culminating in the annual Suva Hibiscus Festival. I still have vivid memories, too, of the wailing and chanting and the relentless day and night drumming from a nearby Hindu temple during religious festivals, when they practiced fire-walking, self-flagellation, piercing and other forms of holy torture.

The kailoma are the ones of mixed heritage, descended from the Indigenous people and foreigners – Europeans and others.

Likewise, I recall the thudding of the lali, the big hollow log drum, calling Fijian worshippers to Christian prayer on Sundays. I remember going to church with my mother, and the glorious singing of the congregation. That gave me an enduring interest in the transcendental, in the sound of the human voice lifted in praise-song. Suva in those days was alive with rhythms. Besides the throbbing of drums – for example, the Cabin Bread biscuit tins played by buskers in the market place – there were the rhythmic handclaps of the kava-drinking schools and what seemed like spontaneous singalongs in villages with strummed guitars and ukuleles always on hand.

Almost as primal was the swishing rhythm of the ubiquitous machete, used for everything from trimming sugarcane stalks, to cutting open coconuts, to slicing up taro, to slashing down bush to make plantation gardens, to chopping up tree branches for open fires.

As a child I absorbed this hubbub instinctively. There was a babble of languages all around, but the default tongue was a kind of dialect pidgin English that included Fijian and Hindi words. ‘Kailoma’ is a Fijian word meaning ‘in-between’. The kailoma are the ones of mixed heritage, descended from the Indigenous people and foreigners – Europeans and others. My brothers and sister and I were kailoma. Although my mother and her extended family spoke Fijian, Rotuman and Tongan, as well as English, we were encouraged to concentrate on learning ‘Pālangi’ English. And in the end, I clung to English as if to a life raft on a stormy ocean. For in that late colonial era, although Fiji was a melting pot it also simmered with ethnic tensions and socioeconomic resentments that sometimes erupted into riots and violence. A few years later would come the civil disturbances of the coup culture that led straight to today’s militaristic authoritarian government.

although Fiji was a melting pot it also simmered with ethnic tensions and socioeconomic resentments

New Zealand was my parents’ adopted land. My father, who grew up in an orphanage, came out from Britain on the toss of coin to join the Royal New Zealand Air Force as a humble recruit, and was posted to Fiji, where he met and married my mother in the teeth of fierce opposition from the RNZAF hierarchy and its covert policy of racial discrimination. He was promptly posted back to Hobsonville air base in Auckland as a punishment. But, as they were legally married, my mother was able to accompany him. So I was born in Tāmaki Makaurau. This was followed by some intricate toing and froing between New Zealand and Fiji before we settled back in Fiji for a few years.

Eventually we migrated to New Zealand and my father left the RNZAF. We ended up living in Māngere East, where I and my two brothers and sister went to Kedgley Intermediate School and then to Aorere College. I am a product of South Auckland, but of old-school South Auckland. Residing in a suburban subdivision felt a long way from the sea. Instead of the ocean there was the lingering smell of tanneries and abattoirs: offal being boiled down at the freezing works, corned beef being cooked for shipment to the Islands. My father was working for Air New Zealand at the airport and my mother got a job in the laboratory at Hellaby’s, where they checked the quality of the canned beef for export.

The standard high-school education back then was all about assimilation into a monocultural monolith, whose national narrative censored and hid social divisions behind a she’ll-be-right philosophy of conformism and mediocrity. Fitting in was everything, especially for those from working-class areas like Ōtara and Māngere.

national narrative censored and hid social divisions behind a she’ll-be-right philosophy of conformism and mediocrity.

I wasn't really into academia, but I did get a good standard New Zealand education and was encouraged by my teachers to enrol at the University of Auckland, but I promptly dropped out. I already knew I wanted to be some kind of writer or artist but I wasn't sure how to go about it – there were no creative writing courses. And I reacted badly to the university's middle-class values, obscure virtue-signaling and examination treadmill.

At school I wrote poetry and I decided to continue to experiment with self-expression while holding down a series of factory jobs. I was listening to Jimi Hendrix and blues musicians like Muddy Waters, and reading James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison and Derek Walcott, and trying to stay out of trouble. I was attempting to write street poetry, protest poetry: most of my political activism was on the page. I became an autodidact, less interested in getting the reductive meal ticket of an arts degree and all the institutional snobbery that came with it (the atmosphere of self-congratulatory Masonic handshakes) than in what I thought of as the enlightenment of self-directed learning.

I was attempting to write street poetry, protest poetry: most of my political activism was on the page.

What I wanted to know was, what was New Zealand culture anyway, and where was I supposed to fit into it? I felt caught between the scapegoat to blame, the law-maker on high, and the law-breaker trying to find an identity in a macho, masculinist society. I suppose, too, I wanted to tweak the nose of received wisdom that clashed with life as I knew it. Society then didn’t seem to want to acknowledge or embrace contradiction the way it does now; instead, complexities of identity were buried deep or painted over. My dual-carriage heritage has been about seeing double, or seeing two ways to understand everything: one my mother's P I way and the other the Pālangi way. Those were the Muldoon Years and I was writing against the grain, against the flow, against the current of the mighty mainstream. I called it anti-poetry.

At school in South Auckland it had been hammered into us not to answer back or to think outside the square. But inside myself I was listening to those drums back in Fiji, I was listening to the church choirs – the feeling of them – and to the conch trumpet, the meke, the ula, the fara and the sway of the rain.

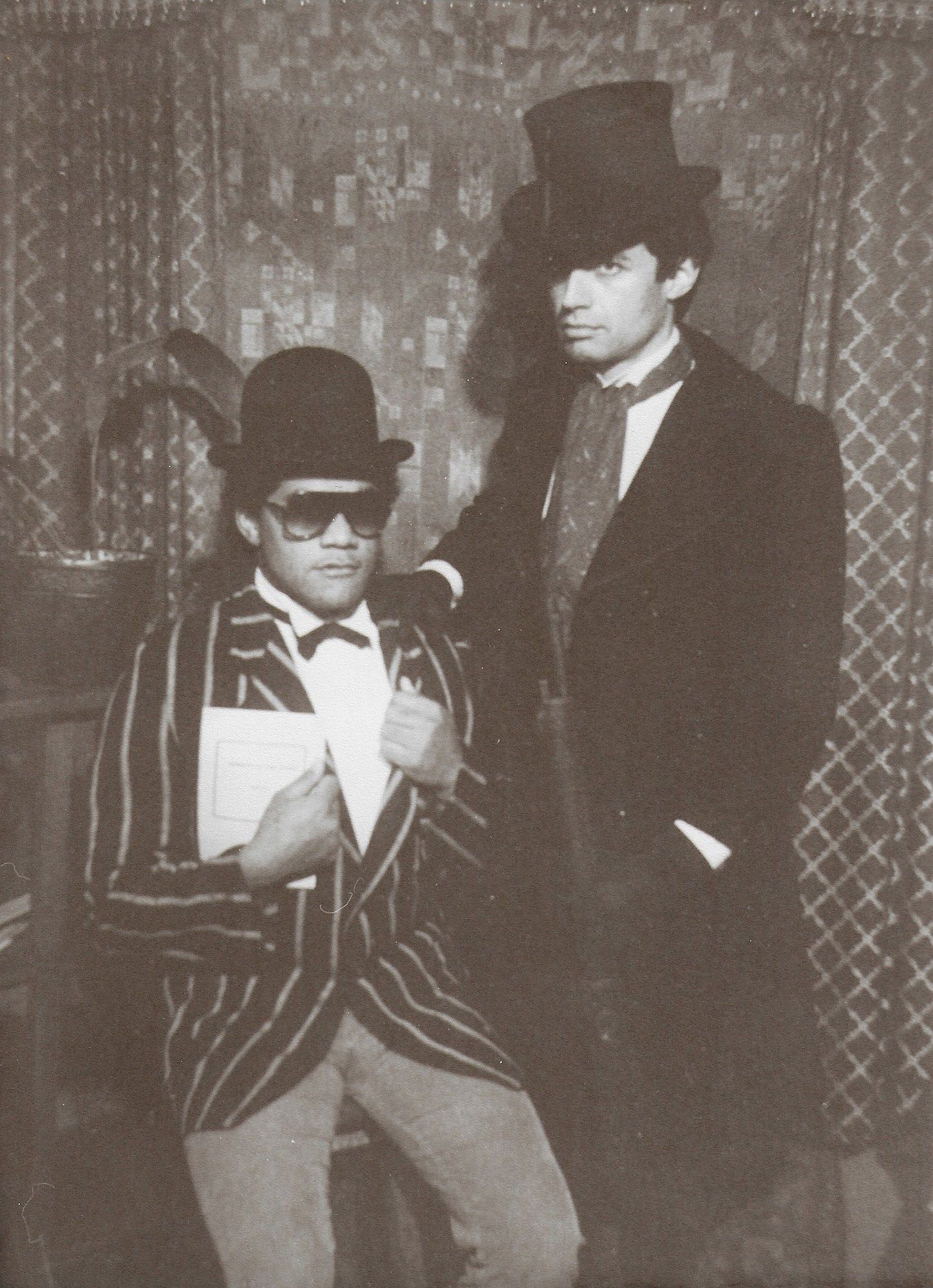

John Pule and David Eggleton on 1983

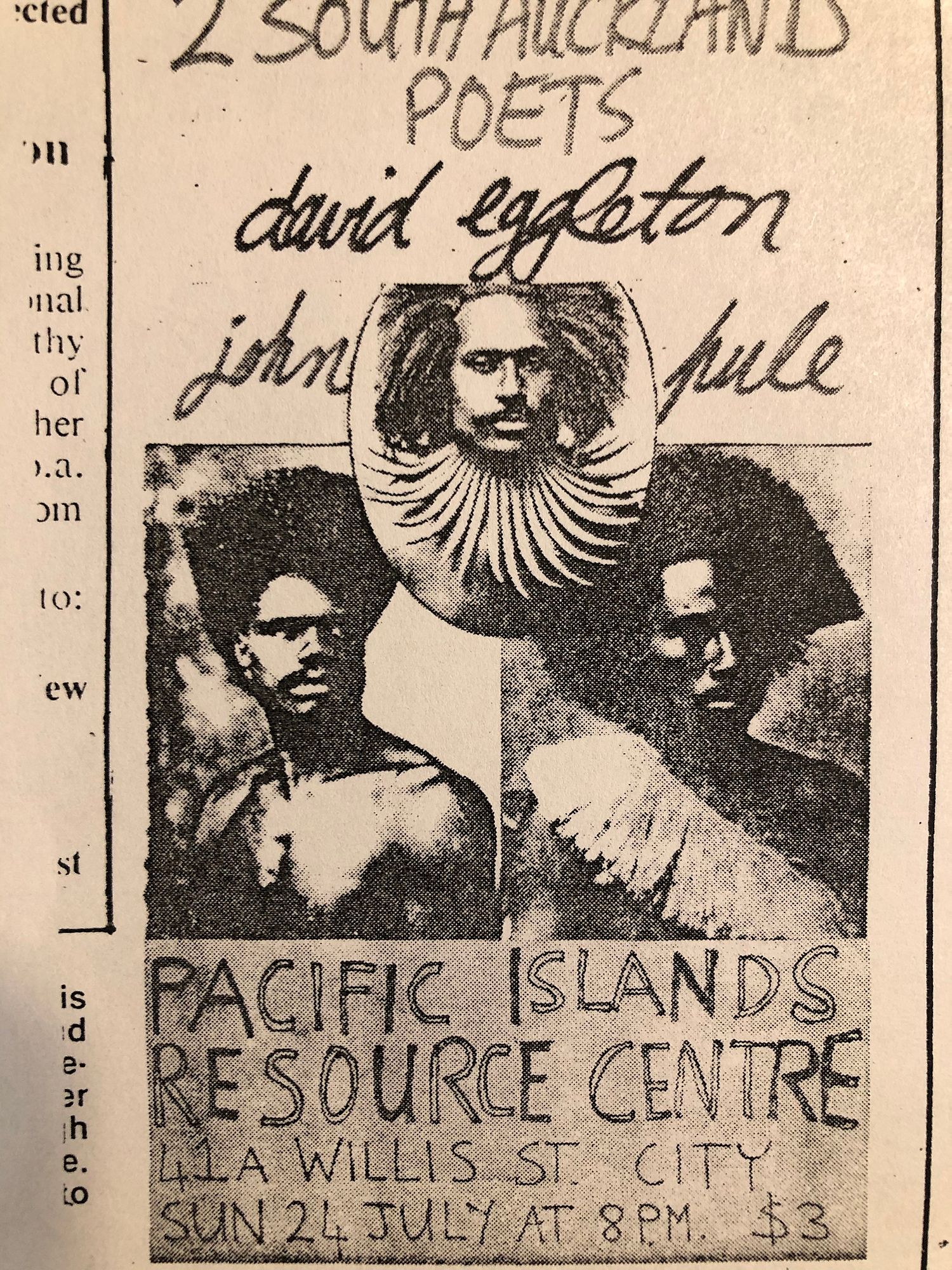

It was here in the early 1980s that I first met John Pule, a young Niuean poet from Ōtara. We clicked, and began performing together. His poetry was more lyrical and romantic than mine. My imagery derived from keeping my ear to the groundswell of popular culture. The poets I was drawn to and influenced by included Linton Kwesi Johnson, Gil Scott-Heron and the Last Poets, as well as rappers like Grandmaster Flash. John and I began busking our poems at places like the entrance to Cook Street Market. For a while we called ourselves The Flying Kamikaze Brothers. We performed at the Dole Day Afternoon concerts in late 1982 and early 1983, and then got invited to be a support act for Herbs at the Gluepot in Ponsonby, then the Windsor Castle in Parnell, and later down in Wellington.

Tour poster 1983

Ponsonby Community Centre 1983

After more performances in the South Island, in Christchurch, Timaru and Dunedin, we decided to go our separate ways. John was getting into painting, and wanted time out. The following year, 1984, the University Students Arts Council organised a national orientation tour for myself and the Māori poet Brian Potiki, which was called NgāReo Whakawhiti Political Voices. Brian founded the first Māori theatre troupe in the 1970s in Wellington, Te Ika a Maui Players, together with Jim Moriarty and Rowley Habib.

My poetry presentations were influenced by the strong oratory traditions of Pasifika culture, albeit in an informal way, but I was also drawn to the frenetic delivery of punk rock performers, and I recited my poetry at Sweetwaters and other rock festivals, and also supported a lot of New Zealand rock bands in pubs and other venues throughout the 1980s. I began corresponding with the British punk poet Attila the Stockbroker and in early 1985 he arranged for me to tour Britain, with the support of the New Zealand Arts Council. I stayed in Britain for most of 1985, featuring regularly as a poet at a wide range of events, from the Ranters’ Cup Final with the Rastafarian poet Benjamin Zephaniah, to the Brixton Poetry Festival with some Jamaican reggae dub poets. I also gave a presentation at the Commonwealth Institute in London, not long after the Patea Māori Club performed there.

I became a poetry performer on the alternative cabaret circuit and performed at the Glastonbury CND Festival on the cabaret stage in June. That summer in London I also won the Street Entertainer of the Year Award for Poetry at the Covent Garden Festival. There were also performances in Holland, Denmark and France. I made arrangements to go and visit Hone Tuwhare, who was on a Goethe Fellowship in Berlin at the time, but I didn't quite make it.

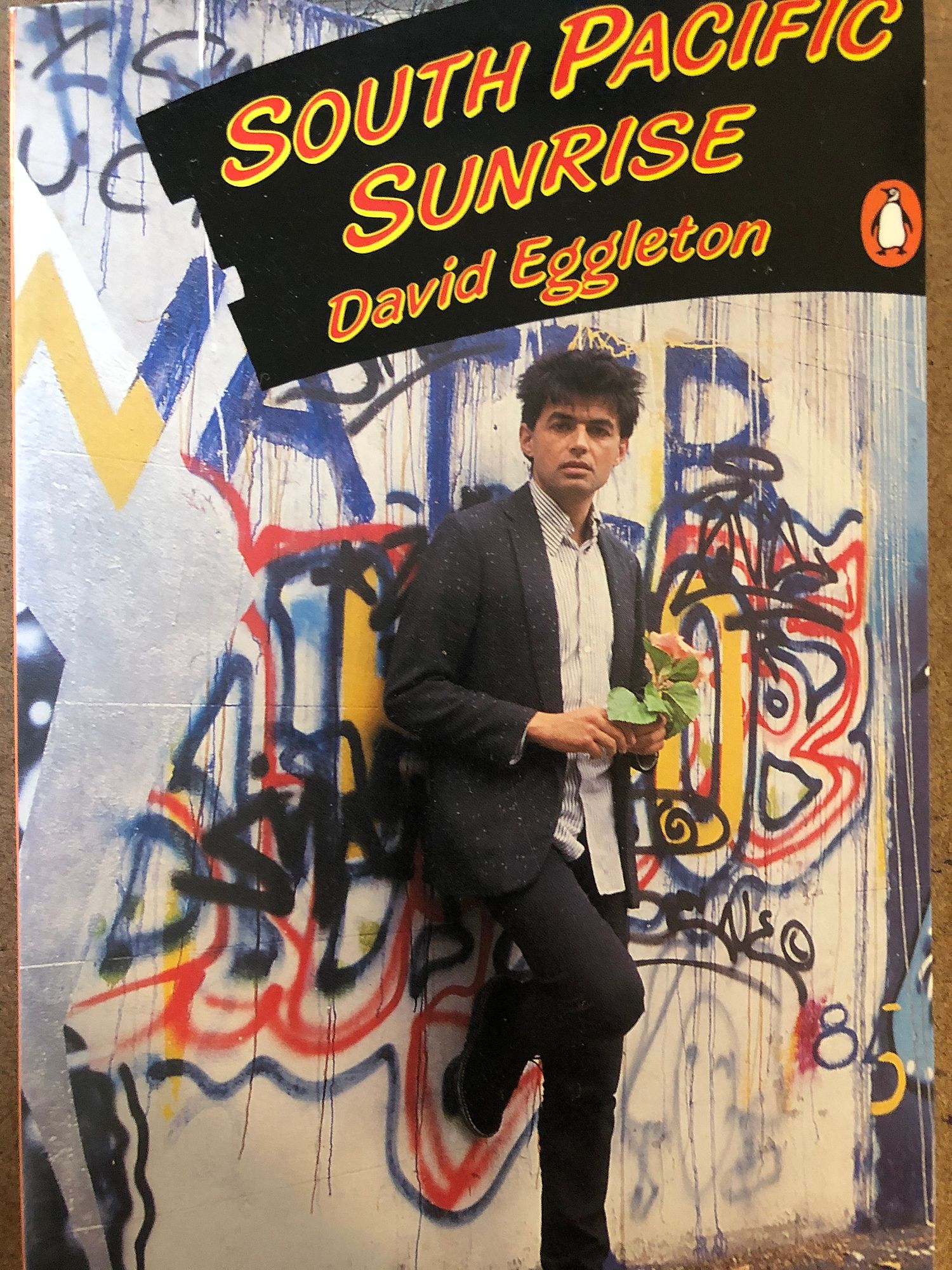

Book Cover South Sunrise 1986

By the end of 1985 I was back in New Zealand, still writing and performing, and preparing for the release of my first poetry collection through Penguin Books, entitled South Pacific Sunrise. This book was co-winner of the PEN Best First Book of Poetry in 1987. From being a poet of Pasifika background from the other side of the tracks, who had started by self-publishing his poems ten years earlier, I had finally made it, after many a twist and turn, into the New Zealand literary mainstream.

Now the Moana Nui is a sea of islands linked by boat, plane and social media. And now my cousins, my kaīnga, living across the Pacific, toast us all, me and my siblings and family, with mai tai cocktails, with mimosas, with mojitos, with Fiji Gold and Mokusiga and Vailima beers. And a gliding frigate bird rides the trade winds, the equatorial breeze between islands, as my guide to the flight path, above the phosphorescent wake of the vaka, the bioluminescent flashes deep within the ocean.

Vinaka vakalevu. Nofo lototo ‘a pea hanga ho ulu ki olunga!

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photograph Edith Amituanai