Representing the Knowledge of Many; Carrying on Qualities of Spirit

We are all a part of the water’s legacy. Ashleigh Taupaki responds to Te Au: Liquid Constituencies at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery.

Harcourt Richard Aubrey – a British surveyor working under Frederic Carrington, aka the ‘Father of New Plymouth’ – arrived in Ngāmotu in 1840 aboard the ship London, coinciding with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi that same year. The following year, alongside Carrington, he played a part in determining the site for the New Plymouth settlement. In 1854, he met Mere Moerangi Mirimata Whanganui Taura, of Taranaki Te Ātiawa descent, and married her. Several decades later, my great-nan Marie Aubrey was born, who later married my great-grandad Matiu Taupaki.

While walking the New Plymouth Coastal Walkway – skirting Te Tai-o-Rēhua and her offshore islands to the west, along the quietly bustling township inland, with all the industrial necessities like an electronics waste mound, metal refineries, and fish processing facilities in the east – I wondered about the ancestors that connect me to this place. The stark contrasts between east and west reflect the cultural disparities of my tīpuna, who both called Ngāmotu home. They would have undoubtedly had their differences. As I walked and climbed to the top of Paritutu, in seeing the snow-capped, clouded spire of Taranaki, I pondered the implications of these differences. When they looked up at the maunga together, did they see an ancestor or a conquest? Were the freshwater streams and rivers seen as life-fulfilling veins in the landscape, or a resource to be made into profit? And were these islands and vast oceans viewed as a phenomenal bump in the colonial road, or a highway of linguistic and cultural exchange?

The stark contrasts between east and west reflect the cultural disparities of my tīpuna, who both called Ngāmotu home

Te Au: Liquid Constituencies at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery highlights a boundless and fluid network comprising nodes (cultural relations, trades and island settlements) and links (watery connections such as rivers, oceans and migratory routes used by seafaring ancestors) that bind our Oceanic people together. Through a diverse collection of works – by a group of predominantly female artists, artist collectives and community groups – water is explored as legacy, as us, and as the flowing relational space (or vā) of which we are all constituents. Each artist draws from a specific body of water in response to the kaupapa of the show; explored through mediums such as video, natural textiles, paper, found netting, concrete, maps, educational resources and oyster shells. We are invited to admire the intimate relations between people and water, and recognise the significance of these places for the individual artists, their communities and environments. Te Au, meaning both water currents and the self in te reo, is reminiscent of two texts that I find myself returning to time and time again. The first being the whakataukī:

“Ko wai ko au, ko au ko wai / I am water, water is me.”

Water, the body, cultural survival and life itself are inherent within Māori beliefs and traditions. This ideology is reflected in the recent development of rivers being granted legal personhood in Aotearoa; the creation of legislation that aims to implement co-governance with Māori and create frameworks to address issues relating to marine and freshwater management; and the persisting grassroots community projects to restore the waterways.

The second text is a passage in Our Sea of Islands, written by Tongan Fijian writer Epeli Hau‘ofa, in which he states:

“Oceania is vast, Oceania is expanding, Oceania is hospitable and generous, Oceania is humanity rising from the depths of brine and fire deeper still, Oceania is us. We are the sea, we are the ocean, we must wake up to this ancient truth.”

This converging and holistic system of te au, waters, peoples and cultures in Hau‘ofa’s description of our beloved ocean, and that notion of connectivity, stands as the cornerstone of Te Au.

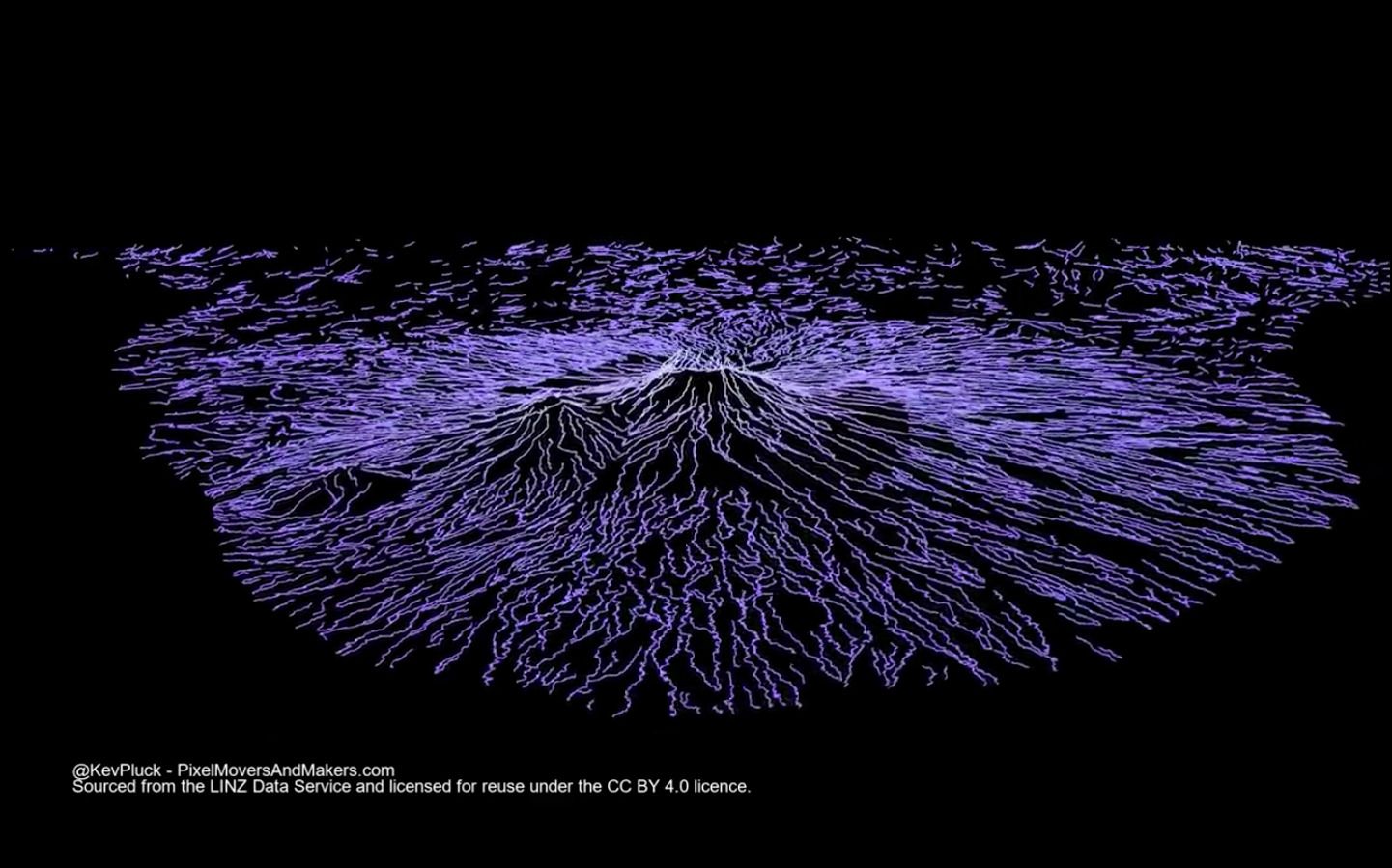

Te wai o Taranaki Maunga / The streams and rivers of Mt Taranaki, NZ data visualisation by Kevin Pluck.

Restoration, Indigenous Frameworks and Community Projects

The forepart and ramp of the gallery houses an assembly of works created by environmental communities on their collective experiences: some of loss, most of hope. If you drove about an hour directly south from the gallery you would arrive at Kaupokonui Beach, where 13 parāoa (whales with teeth) were stranded in the cold Autumn of 2018. The beaching remains fresh in artist Bonita Bigham’s (Ngāruahine, Te Ātiawa) memory. Speaking as part of Te Au’s opening-day programme of artists’conversations, she recalled the difficulty of managing the clean-up of whale carcasses while still honouring the relevant tikanga. With strandings being a regular occurrence for iwi from the north and east, pan-tribal collaboration and knowledge sharing was met with a newfound urgency by mana whenua, who had not dealt with a beaching of this scale in a very long time. Taranaki iwi came together to work and volunteer with experts to dispose of the remains safely. The event was momentous in terms of smell, the history of Taranaki, and the ripples it made in the cultural fabric of the iwi and hapū involved.

In Bigham’s Mātauranga Interrupted, the original nine parāoa that washed ashore are represented by nine blue-green-dyed koru cut-paper works. The placement of each koru figure corresponds to the finding of each parāoa on the beach. Offcuts from the cutting process were used to create negative-space patterns, echoing the curves of the whale–koru and reflecting the physical and spiritual aspects of the occasion. The physical being the whales themselves, the viscera and sweat of the clean-up, and, most importantly, the people. And the spiritual being Rarohenga – where the parāoa travelled upon death – modes of faith such as karakia and a multitude of hui, and the tenacious spirits of all who volunteered their time and labour. In her conversation, Bigham reminisced alongside one of her cousins, Te Aorangi Dillon, encapsulating the urgency and necessity of the challenging times:

“[We were] running off of spirit. It took unity to do this.”

Bonita Bigham, Mātauranga Interrupted, 2018, cut paper, dye. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bryan James.

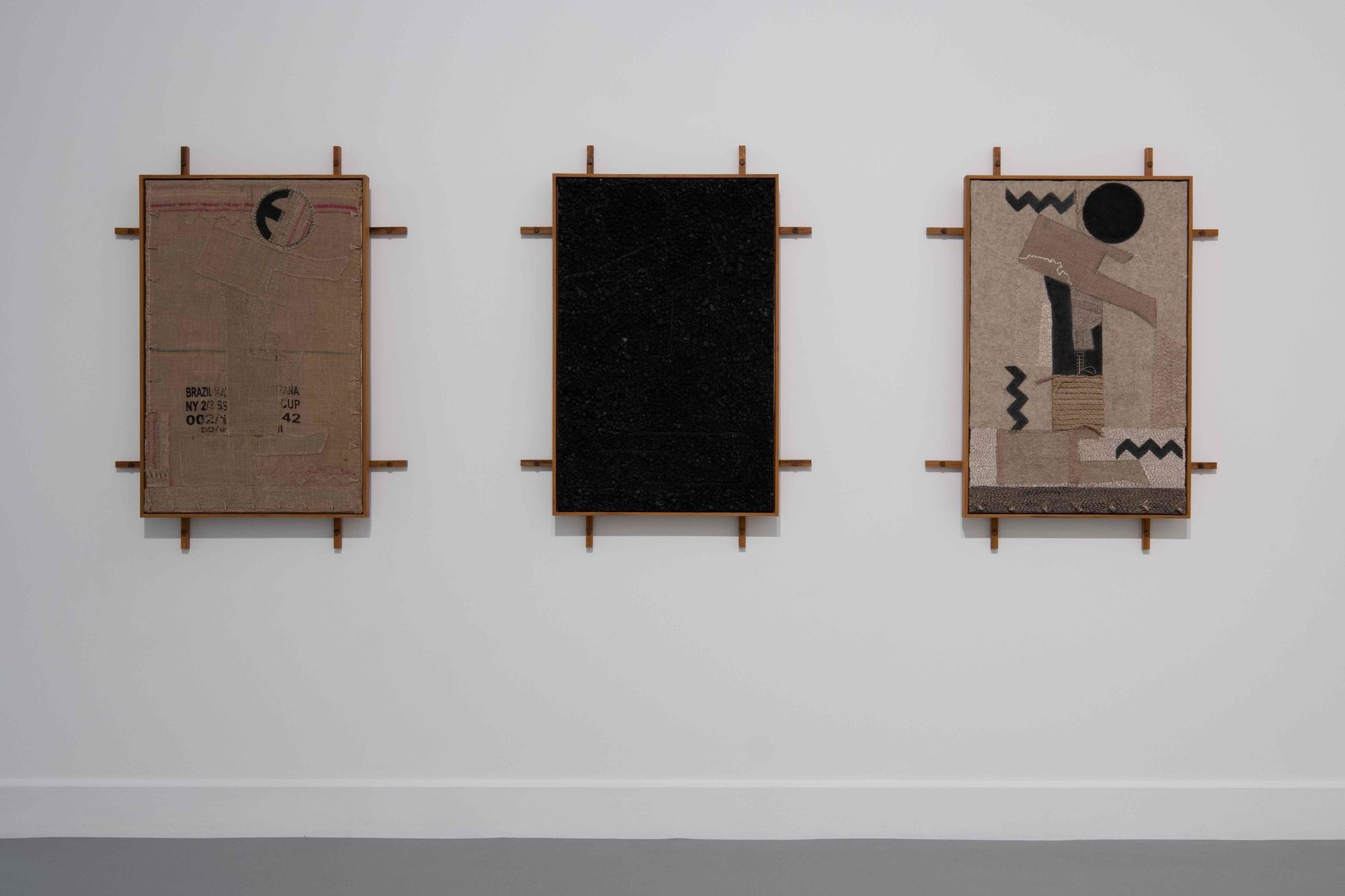

Artist-researcher group Te Waituhi ā Nuku: Drawing Ecologies undertook a series of documentative deep-dives against the backdrop of Waikōkopu Stream in the Horowhenua region. A wall of plans, drawings and experiments titled Notes for the Kuku Biochar Project depicts their trials of biochar as a potentially sustainable resource. This porous charcoal is produced by burning plant matter in a reduced-oxygen environment, which Te Waituhi ā Nuku made on the back property of fellow member Huhana Smith. Biochar has the glittery black qualities of West Coast sand. Its healing properties include the ability to improve soil quality by absorbing carbon, and the filtration of sediment in freshwater. This practice of environmental regeneration is extended through the group’s use of biochar as a drawing tool – most notably in Waewae Pakura, a hemp weed-mat with tukutuku patterns drawn into the textile with biochar, draped over the low wall of the mezzanine floor. Other works by the collective include the large biochar kiln itself, a trio of framed plans collaged with the unique materials used throughout the project, and diagrammatic frameworks for use in other freshwater contexts.

Notes for the Kuku Biochar Project: Ciaran Banks and Huhana Smith, Wero Iti | Little Stabs, 2022, coffee sacks, coffee-sack thread, jute thread, biochar paint (crushed biochar, methyl cellulose), blued tacks, black felt-tip pen, birch plywood; Waro Hou | New Black, 2022, biochar, PVA glue, black felt-tip pen, birch plywood; Kua pahemo te parakipere | Blackberry has gone, 2022, ripple plastic, hemp weed-mat, biochar paint (crushed biochar, methyl cellulose), black felt-tip pen, birch plywood. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Bryan James.

Research agency INTERPRT – consisting of designers, architects and academics – utilises data visualisation as a mapping tool to bring awareness to the environmental atrocities along the Pacific Ring of Fire in their work Unfolded Pacific. The graph key sits in front of the large acrylic map, showing sites of nuclear testing in our oceans and deep-sea mining for minerals such as silver, copper, cobalt and titanium. The group regards these actions as “some of the worst environmental crimes committed against people and nature.” INTERPRT uses data to create resources for environmental justice to mitigate the socio-political conflicts taking place in the Pacific.

Complementing the research-based practice of INTERPRT is the work of Erub Arts, an arts centre located on Darnley Island in the Torres Strait, whose marine dwellers hang from the gallery ceiling. These works are made from abandoned fishing nets recovered from the island’s reefs, which are woven into flocking birds, a turtle and her eggs, and a three-masted sailing boat. The island is explored as a home for humans and nonhumans alike, as Racy Oui-Pitt explains:

“I want to continue to make art that relates to my heritage and promotes our unique island way.”

The arts centre offers an opportunity for locals to learn skills, contribute to the economy of the island, and sustain their oceanic surroundings. This communal effort is highlighted in the accompanying video work Ghost Nets of the Ocean. In its distinct audio element, viewers hear the work of deft fingers twisting and stitching rope, plans being drawn with chalk on concrete, and the crisp sound of wire cutters snipping through plastic netting. INTERPRT and Erub Arts both use threads – networks and the fibres of a fishing net, respectively – to bring awareness to the environmental destruction within the Pacific, and the impacts on communities that rely on the moana.

Erub Arts, Kebi Neur, 2020, ghost net, rope, twine over wire frame. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Bryan James.

Moving Image, Climate Change and the Impacts of Extractive Processes

At the top of the stairs, sharing space with Erub Arts, is a three-channel video work by Angela Tiatia titled Tuvalu. A wave slowly bubbles over sand, a purple and gold sunset glows on a palm-tree beach, and household items succumb to the rising sea. Locals attend to errands and clean up trash washed inland, their vibrantly blue neighbourhoods submerged in knee-deep water. This imagery is beautiful and haunting, depicting the frightening reality of the climate crisis on the small island nation of Tuvalu. The sea creeps up and consumes the landscape, despite the deceptive charm of the seashore hiding the immediacy of the issue. It is an eye opener. Our Tuvaluan neighbours have lost their homes and livelihoods as a result of climate change. As a Pacific nation, flooding as a result of climate change is right on the doorstep of Aotearoa, and is only just becoming a more real issue due to recent weather events across the North Island. As people living in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, these shared experiences will only become more frequent, and victims of these circumstances are anxious to be heard. How do we strengthen the ties across the Pacific and extend further compassion to our neighbours displaced by the climate crisis, and how will these connections as island nations inform the way that we deal with the impending flood that rises slowly towards our doorsteps in Aotearoa?

Angela Tiatia, Tuvalu, 2016, HD digital video, three cannels, 20:32. Courtesy of the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney. Photo: Bryan James.

Oceanic linkages are also conveyed in the video work Vibrante by Chilean artist María Francisca Montes Zúñiga, who traces the path of Portuguese explorer Hernando de Magallanes, the first known European to travel the passage of water that runs between the southern tip of South America and Tierra del Fuego, connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. The passage – self-titled the Strait of Magellan – was one of the only routes connecting the two seas prior to the establishment of the Panama Canal, and was a preferred alternative to the dangers of the open sea below Cape Horn. Magallanes made this trip in 1520 with the intention of seeking the riches of faraway and fabled lands – sponsored by the country of Spain. Despite the naming of the strait after Magallanes, and his ships subsequently famed for circumnavigating the world during this course, Indigenous peoples in Chile had long travelled this body of water for their own purposes. The strait was seen as an opportune commercial route by European settlers, but had always been crucial to the survival of Indigenous seafaring communities.

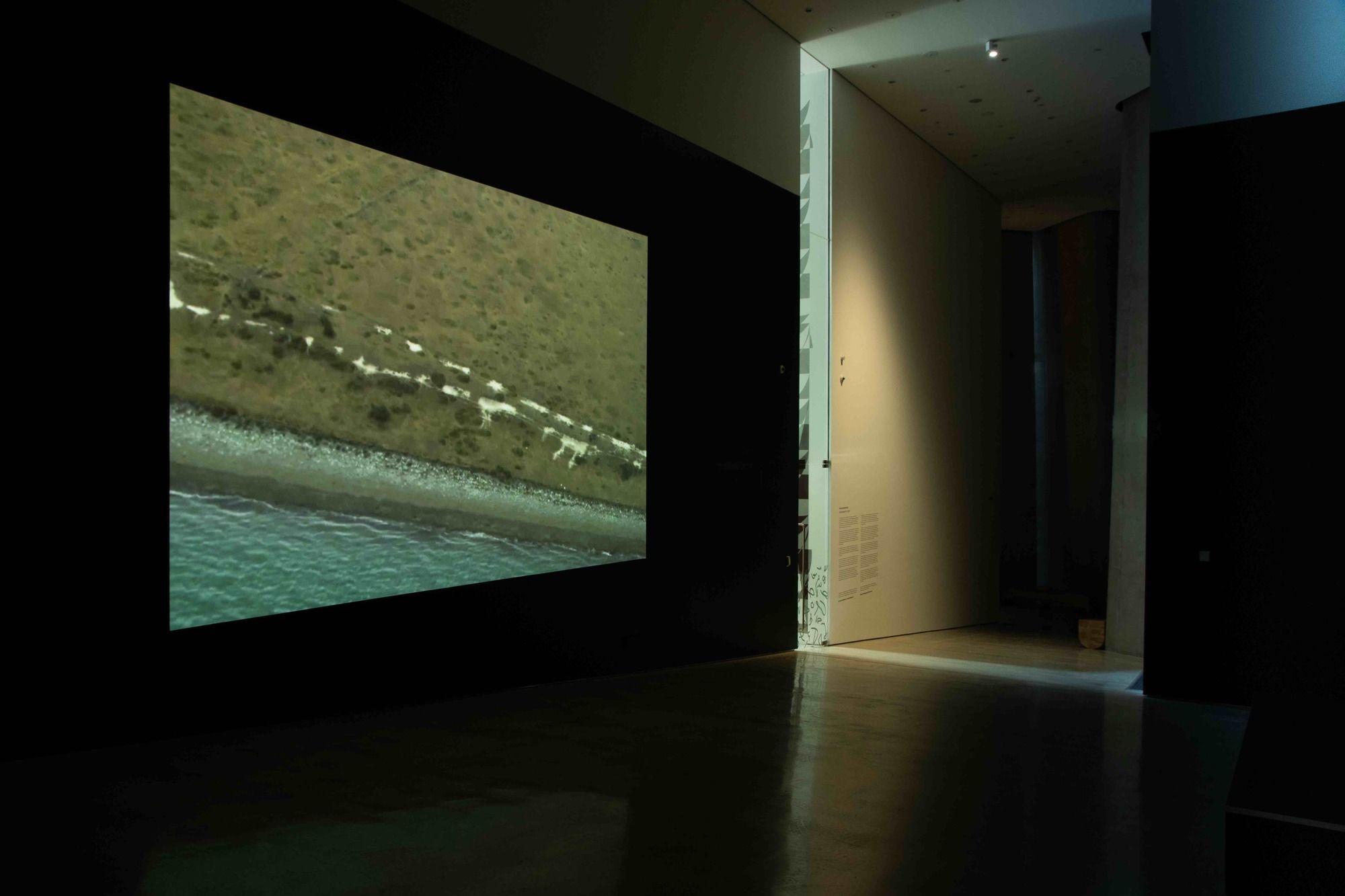

The aerial footage of Vibrante is shaky, as sea is merged with land. Lines converge and the landscape abstracts into a blue trance for over two hours. The work is a symphony of sea and land, colours meshing into one another as the camera operator works overhead. This journey is perilous and long, reflected in the length of the film along a seemingly never-ending coast.

We see the shoreline and base our understanding of statehood, territory and boundaries on those perimeters, ultimately compartmentalising land and sea. And this is perhaps how Magallanes and those who came after him saw the region: a corridor for foreign export and trade; a shortcut for others to circumnavigate the globe and make a name for themselves; and a place to set up strongholds on either side of the passage towards the possession of land and resource, regardless of inhabitants who knew the region before it became the Strait of Magellan.

María Francisca Montes Zúñiga, Vibrante, 2021, HD digital video, 2:25:32. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bryan James.

Habitat is the colourful three-channel video by Taloi Havini, depicting the changing landscapes of the Crown Prince Range in Bougainville as a result of colonial extractive practices. Oxidised copper from mining operations seeps from cliff tops, creating rich-blue waterfalls. At one point, we see from the perspective of the artist rafting the streams that carry mining waste into quarries. The country shifts rapidly as the waters turn a noxious blue and bulldozers contour the earth’s surface. The land is plagued by artificial moonscapes, created by excessive digging, and rivers are rerouted to pool in places they never have before, causing drought downstream.

“20,000 people have lost their lives over 10 years due to human rights violations.”

The audio of the military helicopter abruptly filling the gallery space is a scarily familiar sound for Havini and others who have experienced the horrors of mining enterprises on both land and people. This work stands as a riveting story of loss of land, water, home and autonomy. It is unnerving to wonder at the richness of this altered landscape, knowing that it is alien and purposefully shaped into what is required by neo-colonial powers and industry.

Objects, Textiles, and Reclamation

As the daughter of a cement worker, and also a descendant of the Quandamooka people, Megan Cope makes explicit references to the Australian history of lime burning on the shores of her homeland by using oyster shells and concrete. Lime burning is the process of burning shells and coral to produce lime, which is used as a binder for cement. Middens – disposal areas for shellfish, often used as a landmark for Indigenous peoples and their cultural customs – were a convenient supply for the Queensland Cement and Lime Company to create roads and buildings. Built over tens of thousands of years and reaching heights seven storeys tall, these middens were decimated by this industry. And when the middens were depleted, corporations moved to burning live oysters. Suburbs spread rapidly and Brisbane grew into the metropolis it is now, founded on the eradication of marine life and Indigenous tradition as stated by Cope in her artist’s talk for the exhibition programme.

Cope’s work Foundations 1 consists of two lines of 17 small concrete bricks, with an oyster shell standing upright in each. The shells face towards the stairway, like navigational arrows leading visitors around the gallery. Straight lines and uniformity imply a history of mapping and subdivision, such as the gridded urban planning of the Brisbane region that necessitated the lime burning. In a nearby corner, five concrete and oyster-shell columns that were fashioned in a pipe mould. Extractions 2 repurposes the cement left in the piping used in the making of the artist’s other works. Made using the teeth of a comb, their textures look like tree bark. The works serve as core samples of the contemporary terrain in Quandamooka – a mixture of concrete and oyster shells, steamrolled and neatly gridded atop Aboriginality and relics of a lost past.

Megan Cope, Foundations I, 2016, oyster shells and cast concrete. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photo: Bryan James.

Arielle Walker’s muka and driftwood loom sits in the window space of the gallery, its tone suited to the coffee smells and chatter of the café next door. whatuwai – returning to the sea is a quaint installation of a weaver’s toolset, comprised of a basket overflowing with yarn, half-finished projects and a rock-weighted loom. Brown and green are the prominent colours in this work, mirroring the Taranaki landscape the artist’s ancestors called home. The rocks that weigh the loom were collected from Taranaki waterways, with naturally formed holes allowing them to be threaded, and stones without holes encased in muka lattice. The installation does not sit idly in its glass box. Instead, it evokes a sense of return to the places we hold dearly in our sentiments – the artist promises to return the rocks to where they came from. It reminds me of ecologist Geoff Park’s thoughts about intently knowing a place:

“Reading the landscape is like collage, interweaving the patterns of ecology and the fragments of history with footprints of the personal journey.”

Walker shows a patience towards her landscape in her collection process, and extends this understanding into her delicate practice of weaving and dyeing. By immersing herself into these familiar paths along awa and moana, a private language develops between artist and place.

Arielle Walker, whatuwai – returning to the sea, 2022, driftwood, stones (gathered from Herekawe, and Tongapōrutu awa, to be returned after use), clay, muka/harakeke, tī kōuka, angiangi, ribwort plantain, dandelions, onionweed, Queen Anne’s lace , wool. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bryan James.

At the top of the main gallery stairs hangs Ruha Fifita’s Lototō, a five-metre by three-metre ngatu work gently curving towards those walking up the steps. Ngatu is a Tongan textile, created by beaten, stretched mulberry bark. Pieces of ngatu can be glued together to make bigger pieces, which are then decorated with traditional motifs and storytelling. Ngatu is typically kept aside for ceremonies and is considered a taonga in Tonga. The tradition has been passed down over millennia and reflects a changing textile language as a result of time, migration and globalisation. It is a laborious process that requires many hands, and Fifita’s community’s back-breaking effort into the work is evident. Lototō is a Tongan word, which encompasses concepts of humility and generosity – as emphasised in the ngatu workshop held by Fifita and the IVI collective at the gallery to accompany the work.

My readings of the work evolved as I spent time with the collective during the workshop. The ngatu hung as a backdrop to our meeting, and its yellows and browns warmed up the room, creating ease for curious passers-by to partake in the making process. Some of us prepared the material, cutting cane, while others stitched pre-cut cane onto pre-prepared motifs to be used later as stamps; others gave massages to weary shoulders, and allocated roles for newcomers. All of this was done surrounded by the vibrational sounds of the ngatu being beaten by expert hands. In cutting cane, I learned that the motifs that run horizontally through the centre of the piece form a reversible pattern to depict humpback whales breaching and birds flocking at sea, as observed by Pacific ancestors and contemporary scientists alike. By listening to neighbouring conversations, I discovered that each pigment held a unique process, with some originating from volcanic earth, and others from the procurement of native flora.

Ruha Fifita, Lototō, 2016, earth pigments (‘umea), natural dyes (nono, koka, tongo) and candlenut soot (tuitui) on beaten mulberry bark (feta‘aki). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bryan James.

In sharing lotu (prayer), I was reminded of the power of community, which extends past the physical meeting in the gallery space and into these ancestral connections through the continuation of tradition, collaborations with the earth, and the spirituality of sharing in song and self-reflection. While in talanoa with writer Faumuina Felolini Maria Tafuna‘i, Ruha Fifita spoke of her aspirations and influences as an artist, and naturally paid tribute to her tīpuna in a statement that I have adopted as the title for this essay,

“[I am] representing the knowledge of many [and trying to find] qualities of spirit to carry on.”

On the first day in Ngāmotu, Anglican Reverend and local historian Jay Ruka led our hīkoi through the headstones at Saint Mary’s Anglican Church, Aotearoa New Zealand’s oldest stone church and a former pā site. The epitaphs keep the memory of British soldiers involved in the 19th-century Land Wars, whilst berating the “rebel maories” who fought to defend their livelihoods. This complex and violent history in Taranaki conveys the cultural disparities that have left tāngata whenua dispossessed, and have been detrimental to the welfare of the natural ecosystem in a bid to expand and control. The artists of Te Au: Liquid Constituencies recognise these cultural tensions in their own contexts, observing the impacts on their own waterways. It is a similar story across all of the artworks, despite differing intentions, backgrounds and practices. Many are solution-based, merging Western and Indigenous sciences to restore rivers and shorelines. Others bring awareness to the long-told stories around water, manifesting sentiments in the hearts of the audience to inspire action in their own lives. Each artist has their own body of water in mind, and perhaps we do too.

Te Au: Liquid Constituenciesat Govett Brewster Art Gallery

Ngāmotu

3 December 2022 - 20 March 2023

Curatorium: Zara Stanhope, Simon Gennard, Ruth McDougall, Beatriz Bustos Oyanedel, Huhana Smith and Megan Tamati-Quennell

*

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.