‘I am a Pākehā because I live in a Māori country’: Pākehā Identity and the North Island Myth

Michael Grimshaw asks what it means to be a Pākehā New Zealander, and calls for Pākehā to demythologize and refute the toxic myths of Pākehā indigeneity.

Following on from his essay 'The South Island Myth revisited,' Michael Grimshaw asks what it means to be a Pākehā New Zealander, and calls for Pākehā to demythologize and refute the toxic myths of Pākehā indigeneity.

The question of what it means to be a Pākehā New Zealander is centrally linked to the question of how identity arises from living in a new landscape. One aspect of Pākehā identity that arose in response to that question are the damaging myths that Pākehā can be a new indigenous population, an idea that this essay will refute. I deliberately use the term ‘damaging’ because these myths are a political and cultural act that seek, implicitly and explicitly, to sideline and supplant the existing indigenous population.

Such myths arise when a colonial population variously proclaim that they are now, that they have become – or even are in the act of becoming – indigenous. We need to be clear in our understanding that for settlers to proclaim an indigeneity is a political gesture and statement of the wilful dispossession of those who are indigenous. Not content with taking their land, the settler now determines to take over the indigenous identify and supplant with their own. Such claims of a new indigeneity therefore continue colonization into the present day.

These myths began early in our nation’s history, as suggested in this lament from writer ARD Fairburn, writing from Wiltshire, England in 1932, such identity involve appropriation:

I’m in a foreign country, among foreign people and foreign trees and foreign hills and I feel out of touch with the sources of life. So maybe I’ll go back and disinter the Polynesian in me and let him out on the rant-tan.[1]

In New Zealand arts and letters it is traditionally the South Island landscape with its supposedly empty interior that provided for the articulation of an identity for Pākehā settlers. Settlers articulated this identity due to the rise of a particular form of cultural nationalism that manifested in unrelenting romanticised tourist images of unpeopled mountains and lakes in the 1930s and 1940s. The movement’s three main exponents were the poet and later editor of the journal Landfall, Charles Brasch, the poet and critic Allen Curnow, and the essayist M.H. Holcroft. All three were South Island born and their creative undertaking - derived from the pathetic fallacy, but infused with the ethos of cultural nationalism - was to respond to the inland hills, mountains, waterways and plains as a place for Pākehā settlers to both derive and inscribe upon their identity.

To create this identity, the South Island had to be conceived of and wilfully experienced as a providential empty land. For instance, poet and essayist D’Arcy Cresswell called the South Island a ‘barely inhabited’[2] land. Creswell also mythologised the island when he said, ‘there was never to my knowledge, so large and so fair a land to be had for the taking.’[3] Seeing the South Island in this way enabled a form of settlement and identity to be developed that was different to that of the North. While the North Island was a site of conflict with Māori, in contrast the South Island was the site of conflict with an indifferent nature. Instead, it was an empty landscape and environment perceived to be without history or landmarks, and therefore ripe for landmarks created for the new people of that land, the Pākehā settlers.

A central task for these new New Zealanders was to create meaning from their environment, or as Charles Brasch declared in ‘The Silent Land’:

The plains are nameless and the cities cry for meaning

The unproved heart still speaks a vein of speech[4]

Such meaning creation became known as the South Island myth.[5] Precisely because the land was seen as empty and uncontested, it was taken as a blank slate on which to inscribe a cultural nationalism. While the act was a wilful blindness and a deliberate excising of Ngāi Tahu, more than that, the turn to the interior was analogous to an interiority of the settler self. In short, settlers believed that the environment of the South Island mirrored the depths and magisterial possibility of new New Zealanders, and a southern identity and claim of a settler indigeneity arose from this romanticised sense of self in the ‘empty’ island.

While poet and critic John Newton has dismissed the South Island myth as the vestiges of landscape Romanticism and the pathetic fallacy, a more nuanced understanding is required. In a 1940 essay in his local newspaper the Christchurch Press, Alan Curnow wrote on ‘the prophetic accent of our late contemporary English poets,’[6] concluding:

The real prophets of our time are those whose sensitive minds can grasp what adaptation means in emotional and personal terms, and express in their writings the vital struggle of man with his environment.[7]

As Curnow notes, the South Island myth was a spiritual undertaking by Pākehā settlers attempting to inscribe a meaning on to and out of the ‘empty’ land. As I have argued elsewhere[8], we have been too quick to dismiss the spiritual journey because we have read the South Island myth in literary rather than religious terms.

Yet the South Island myth does not exist in isolation; there also exists the myth of the North Island. In 1934 Fairburn published an essay in Art in New Zealand entitled ‘Some aspects of New Zealand Art and Letters.’ I want to argue (perhaps heretically) that the South Island myth is a reaction to Fairburn’s piece (at least in part), which I term a form of North Island myth. In his article appear all of the elements that Brasch and Curnow come to argue against when creating the South Island myth, while Holcroft, somewhat paradoxically, can be seen to take the arguments as his starting point.[9]

Fairburn’s central point is what I term the ‘dislocated exile’ and his claim is as follows:

We are British seed, planted not so long ago. We have, as we are never tired of pointing out, no tradition of our own. In a word, we are Englishmen born in exile. Set down in this evergreen unchanging countryside, there is constant pain in our hearts, a nostalgia for the vast movements of the English seasons, for the honey-coloured haze that shrouds the northern landscape on even the brightest summer day, for the intoxicating beauty of springtime in England, and for the endless melancholy of autumn. These motions of the earth and air we are lacking, except as a pattern in the blood, which finds no correspondence in nature. A dynamic race in a static environment: stagnation will precede, and cloak, adaption.[10]

Fairburn carries on to note all the usual nationalist tropes: seasonal disjunction, nature-worship, the hard-light thesis of a distinctive New Zealand clarity of light and the sacred-mythological task of young New Zealand writers to ‘…by his creative energy, give life form and consciousness.’[11] As critic and historian Eric McCormick observed in 1940, Fairburn’s essay ‘might be regarded as the unofficial manifesto of the younger writers, by implication in the work of the writers themselves.’[12]

The South Island differs from the North so much as to be almost another country.

So it is against this North Island myth, the green exile, the land without seasons, that Brasch and Curnow wrote about the South Island. Holcroft occupies a place between, taking these sentiments as a starting point to locate a new mythology of New Zealand. One further influence on the North and South Island myths was the essay by T.H. Scott published in Landfall in 1950. It begins with what has become a cliché of socio-cultural and environmental determinism and identity:

When I left the North Island and came to the South to live, I felt immediately and overwhelmingly that I had come to a quite different country.[13]

Others expressed similar sentiments. Alan Mulgan wrote in 1935 that ‘the South Island differs from the North so much as to be almost another country,’[14] and that the differences were expressed ‘politically, socially and economically as well as geographically.’[15] As Scott sees it, the central difference between the North and South islands is that, in the North, he is always aware of being on an island, whereas, in the South, he is in ‘what could have been a continent.’[16] Scott further emphasizes that, for him, the North was ‘a cultivated garden between mountains’[17] where the bush had been cleared and human impact and settlement was clear and present. With these dialogues, the conceptions of the two islands and the settlers who lived there began to separate.

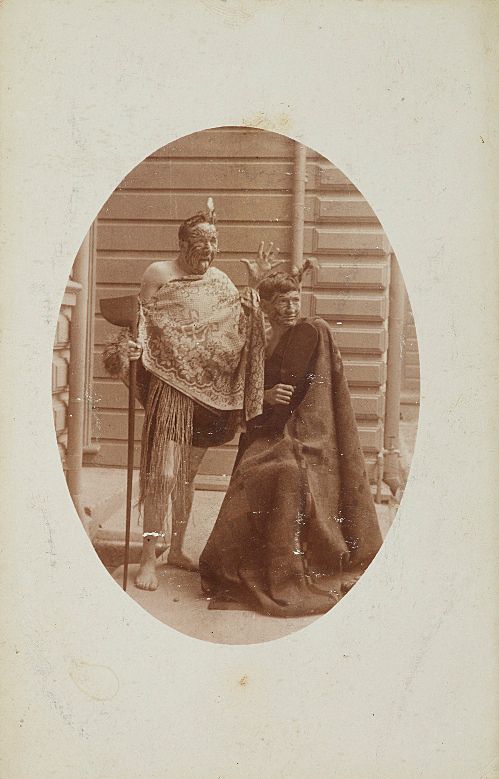

So what of the North Island, an island with a much larger Māori presence, a island of bush and coastal settlement; an island where more people settled and continued to arrive to settle? For it is true that the landscape, the ecologies, and the environment are different in the North Island. There was no possibility, as in the South, that settlers could claim an identity and indigeneity that conceptually erased Māori, primarily due to the density of Māori population. For instance, in a 1938 essay in the left-wing journal Tomorrow it was noted:

As lately as January 14 (1937) a Christchurch paper printed a paper congratulating you and me once more on there being no native problem in New Zealand. It must have been quite easy to sit in a swivel chair in Christchurch and feel sincere about writing such stuff. But in the North Island where 8% of the population are Māori, there is no Pakeha who would not pour derision on it.[18]

Yet there was (and is) a definite North Island myth that arises from the differing experience of Pākehā settlement in that island. As Alan Mulgan reminded the southern mytholgiser M.H. Holcroft in a letter in 1941:

…I think you know more about the South Island than the North, and you do not mention the influence of the sea. This influence seems to me important. The sea is in our blood, whereas to take another young British country, it is not in Australia’s. Sea and mountains; what effect will they have?[19]

Mulgan suggests that the North Island myth is primarily a coastal myth and secondarily, a myth of a struggle with the bush that, in the end, needed to be tamed and burnt. The interior was the domain of Māori and bush, and many Pākehā settlers who arose from the North Island interior tended to relocate to the coast. For instance, Frank Sargeson, whose writings advanced a view of New Zealand life contrary to the solitary man in the empty Southern wilderness noted of living in the North that he was ‘forever bound to the hilly stump farms of the King Country…which were often abandoned within a few years after the bush had been cut and burnt.’[20]

North Island myth is primarily a coastal myth and secondarily, a myth of a struggle with the bush.

A similar myth, comic in its pathos, of interior struggle and failure in the North occur in Me & Gus, the stories of Frank S. Anthony, which detail the demands of an attempt to farm amidst the bush of inland Taranaki. The stories are reminiscent of the struggles of John Mulgan’s Man Alone on the Northern volcanic plateau, and then in the Kaimanawa ranges ‘surrounded and drowned in the hills and bush, safe and alone and submerged’[21] in ‘the dark loneliness of the bush.’[22] Mulgan continues:

…real bush…deep, thick and matted, great trees going up to the sky, and beneath them a tangle of ferns and bushlawyer and undergrowth, the ground heavy with layers of rotting leaves and mould. To go forward at all was difficult, held back all the time by twining undergrowth. The air was dark and lifeless; it was rich with the sweet rotting smell of the bush, and only stray glimpses of light came through the trees above.[23]

In comparison, while in Northland Anthony’s protagonist Johnson recounts, ‘they were good days along the coast,’[24] a coast to which Johnson returns after his travails in the bush-clad, empty interior; a coast which enables him to leave.

This is the central difference of the North and South Island myths: if the South Island myth is a pathetic fallacy of interiority, of a terra nullis for a new identity to be inscribed upon, then the North Island interior allows no such attempt. Rather, the North Island myth is an identity derived from being coastal dwellers, of a people and a society that, to find meaning, does not turn inwards like the settlers of the South. Rather, North Island settlers turned to the coast, to the liminal zone of the beach, and to that meeting place where ‘the last of the golden weather’ is played out.

The North Island myth is therefore an alternative landscape to the South, and an environment where a new identity for Pākehā settlers was possible. The painter Colin McCahon noted while writing to Charles Brasch in 1953 about his relocation to Auckland from the South Island, ‘I feel at home… it’s a lovely place to me – with a warmth that Christchurch never has. Not mock English or Scottish but becoming New Zealand and possibly what one would call pacific.’[25] He further notes: ‘it’s good to feel at home and a foreigner.’[26]

North Island settlers turned to the coast...to that meeting place where ‘the last of the golden weather’ is played out.

The perceived shift to the Pacific, which is a result of climate, topography and coastal location, becomes the central determinant of what I term the North Island myth. It is a very real sense of being ‘Pacific’ that even Brasch identified by the early 1950s, after journeys to the North Island:

New Zealand, it is plain, has no future as a watered-down tasteless Britain of the South. It is as a genuinely pacific society of mixed blood, mediating between east and west, that we may hope for its emergence in time to come with gifts of its own to offer the world.[27]

Yet while Brasch’s prophecy of a harmonious ‘mixed’ society is yet to be fulfilled, the intention was supported by the Pākehā settler identity that rose from the North Island myth’s and was based on coastal location and environment. Because of the Māori presence, Pākehā settlers could not claim an indigeneity as happened in the South Island. Rather, from the 1950s, we see the beginning of claims of a transition of Pākehā settlers in the North Island into a new Pacific people. For instance, the call in the 1952 Poetry Year Book was ‘to be a pale-skinned Polynesian instead of a sun-tanned, transplanted European…’[28] arising from ‘an adjustment of English practice to meet the needs of those stranded in the South Pacific.’[29]

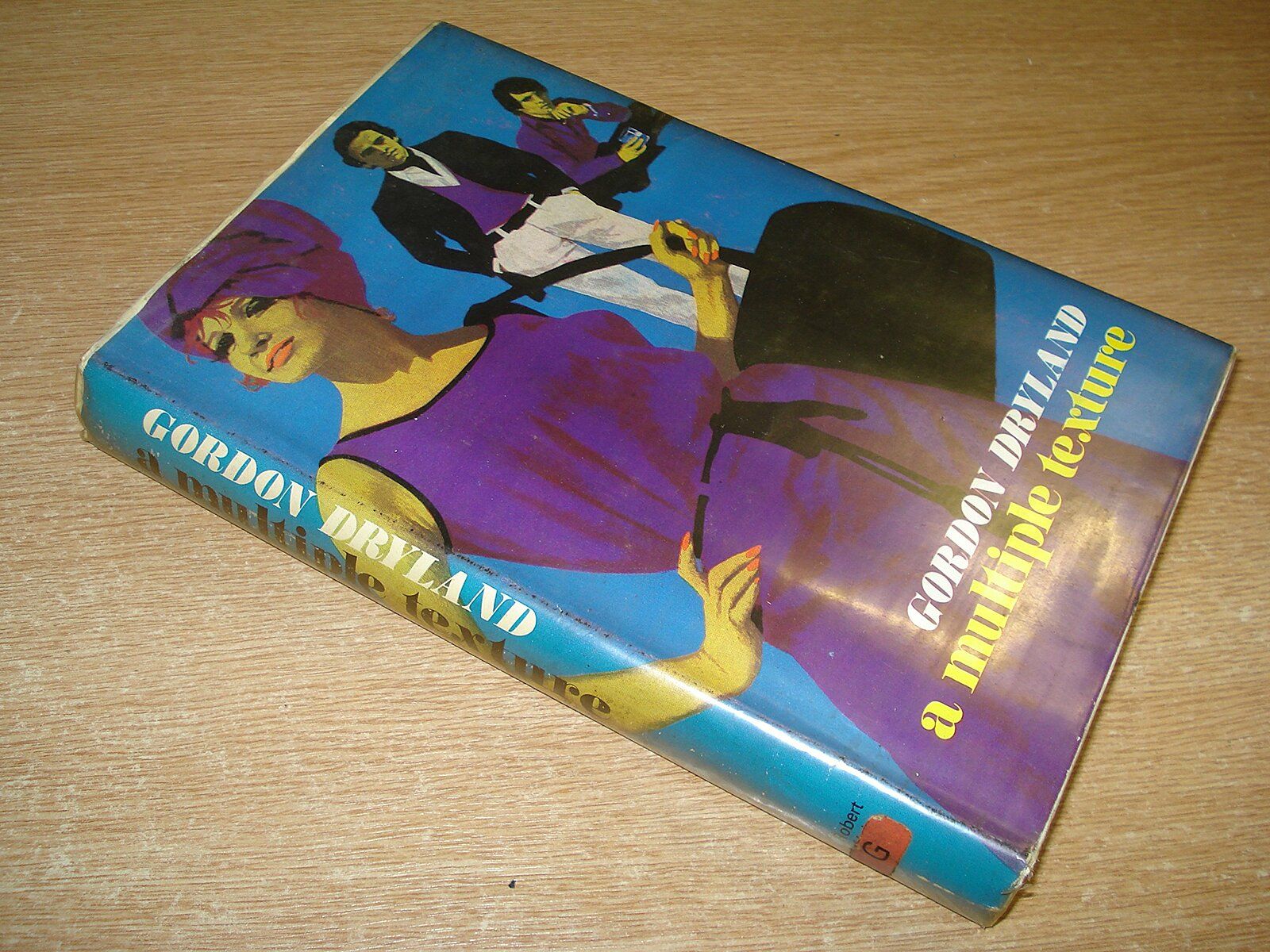

The transition from Pākehā settler to a new Pacific people is discussed by the novelist and playwright Gordon Dryland in his 1973 novel, A multiple texture. Set in 1957, Dryland described the changes occurring in the North Island Pākehā settler identity due to their environment and coastal location. A new New Zealander coastal dweller is positioned against what is termed the regional conception or ‘real New Zealander’:

a particular New Zealander who – reflects – this environment – the rivers, the bush, the mountains and all the rest of it, the whole of this uncharitable, violent, exhausting, demanding sprawl of islands. This character, is believed to be 'the real New Zealander'… the New Zealander’s idea of what a New Zealander should be.[30]

Allied to this concept was the Pākehā settler’s desire to change their environment, which was contrary to the Māori response at the time who, in general, were ‘not concerned with changing his environment. This is not at all a Polynesian characteristic. The Polynesian adapts himself rather than his surroundings.’[31]

In Dryland’s novel we see the rise of a new Polynesian-derived and imitative Pākehā settler who, like the main character Barton, is a coastal dweller and adapts themselves to their North Island environment. In one scene Barton states:

I’ve stopped being a romantic. I’ve discovered that I like to live on the coast. I like the sand and the sea, and yet the bush if I need it, is within easy motoring distance…I’ve stopped feeling the obligation to accept the challenge. I shall never again hurl myself against the elemental New Zealand. I’ve lost the desire - and New Zealand herself doesn’t give a damn.[32]

From Dryland’s characterisation, the North Island myth is that of a Pākehā settler who, like someone of Polynesian identity, adapts to living on the coast. The self-conceived ‘new Polynesian’ focuses on their new homeland, for as Dryland’s character states: ‘he hasn’t a thought of “home.” He doesn’t cast his mind back, even unconsciously, to a homeland.’[33]

The North Island myth is that of a... self-conceived ‘new Polynesian.’

As also suggested in the novel, the identity of coast dweller is environmentally determined. Dryland’s character was born in Auckland and being an Aucklander makes you this type of ‘new Polynesian.’ This is very similar to the way in 1952 the historian, poet and passionate Aucklander Keith Sinclair outlined the way New Zealander identity is constructed in a discussion of making New Zealanders out of ‘new’ New Zealanders (that is, new European migrants):

What is a New Zealander? The consensus of opinion is that he is a product not of art but of nature, and the birth and growth of children will settle the nationality of their parents, who will see their children “swallowed up in a new land.”[34]

The statement is significant because Sinclair as a poet and critic had rejected the South Island myth as the product of South Island Englishmen.[35] His rejection was outlined in ‘The Chronicle of Meola Creek,’ a poem based on his boyhood in Auckland; the poem takes its name from the creek that drains into the mangrove swamps and mudflats of the Waitematā harbour at Point Chevalier where Sinclair grew up.

Sinclair’s poem is a direct engagement of both Curnow and Scott, taking as reference points both Curnow’s famous lines of South Island and cultural nationalist hope: ‘Not I, some child, born in a marvellous year, / Will learn the trick of standing upright here,’ as well as T.H. Scott’s statement in ‘South Island Journal’ in Landfall: ‘yet many do live their lives here as natives.’

In the ‘The Chronicle of Meola Creek’ Sinclair recounts:

When we were the people our time had grown,

The poet, the artist, the prophet we meant,

We launched our youth in the flames of the men

And the mangroves, meeting along the creek,

The Towns that our eyes had known.

We were brave, were mapping the coasts of mind

Where we strive to plant, in the soil of speech,

The truth that was born on a Rock, a Creek:

Our random home, grown native now,

Was the pith in life that our past assigned.[36]

Sinclair’s words point to is the way the rise of a North Island myth acted as a counter-myth to the South Island myth. Of course, the claim from settlers of indigeneity as a ‘new Polynesian’ is as problematic as that proclaimed in the South Island myth. Such claims allowed historian John Beaglehole to state in 1961 that:

…the critical fact about New Zealand since the war may be the relationship of Maori and Pakeha – not Maori and European, since the white-skinned is now as native to the country as the brown-skinned. It should have a life and inheritance in art and letters.[37]

What Beaglehole ignores is that Pākehā settlers can only claim indigeneity if they downplay, depoliticize, discredit, and diminish (take your pick) the indigeneity of Māori as Tangata Whenua, and dismiss and depoliticize the use of the terms ‘indigeneity’ and ‘indigenous’ as exclusionary and a form of resistance.

Both the South Island and North Island myths act to position a white settler indigeneity that, by claiming a new environmental essentialism and an ecological vitalism, work to make colonialism and its on-going legacy easy to dismiss. For whether South Island continental dweller or Northern coastal dweller, whether Pākehā indigeneity in the supposedly empty land, or newly indigenous pale-skinned Polynesian on the northern coastlines, a Pākehā settler claim of indigeneity is one that is impossible, and a claim that too easily, implicitly, and sometimes explicitly seeks to forget colonialism and to deny its reality into the future.

Such myths continue into the present day and are variously articulated in the name of a new nationhood, the access to wilderness and beaches, the settler ownership of farmland against foreign investors, and increasingly, and most ironically, by white settlers against the immigration of more recent, mostly Asian migrants.

But we who are Pākehā must never forget that such myths and expressions arise in attempts to depoliticise bicultural debates in the name of a settler indigeneity, and also that claims of multi-culturalism and new nationhood likewise seek to sideline Māori as first people. Both myths, whether of a new white southern indigenous people or of new northern pale-skinned coastal Polynesians are postcolonial attitudes and identities that serve only to continue the inequality and dispossession of Māori under Pākehā settlement.

Environment and ecologies are always political, as is the term 'indigenous.'

Yet perhaps there is a third option as identified by Ani Mikaere, barrister, academic and philosopher of Māori law and identity, who concluded an essay in 2004 on this question by, to my surprise and honour, stating:

Perhaps it is Mike Grimshaw who best addressed the question of Pākehā identity when earlier this year he observed: ‘I am a Pākehā because I live in a Māori country.’[38] When you think about it, there is nowhere else in the world that one can be Pākehā. Whether the term remains forever linked to the shameful role of oppressor or whether it can become a positive source of identity and pride is up to Pākehā themselves. All that is required from them is a leap of faith.[39]

Having thought about Mikaere’s comments for over a decade I want to argue that the leap of faith needed is to know our myths and to demythologize them; to be aware that we as Pākehā settlers can not claim any indigeneity whether we live in the North or South islands. For environment and ecologies are always political, as is the term ‘indigenous.’ For Pākehā settlers to claim an indigeneity not only wilfully ignores that the environment and ecology of New Zealand is Māori first and foremost, it also politically mythologizes ourselves to wilful delusion.

The references footnoted in this essay are available as a PDF.

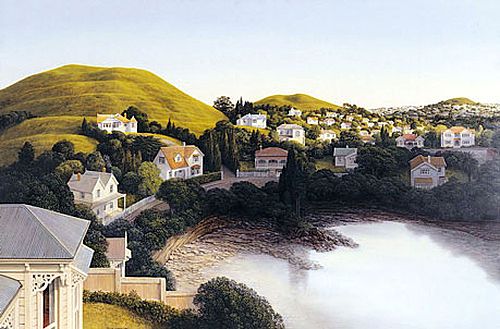

Feature image: Kororarika, Bay of Islands, New Zealand by Charles J Pharazyn, 1843. Te Papa Collections.