He mau mana‘o no ko Honolulu Hō‘ike‘ike Hana No‘eau o nā Lua Makahiki: Thoughts on the Honolulu Biennial

Artist, writer and curator Léuli Eshrāghi talks ecology, militourism and Moananuiākea in response to the inaugural Honolulu Biennial 2017: Middle of Now | Here

Artist, writer and curator Léuli Eshrāghi talks ecology, militourism and Moananuiākea in response to the inaugural Honolulu Biennial 2017: Middle of Now | Here

Namu‘a is a small, natural island sanctuary in the Sāmoan archipelago. In this seemingly pristine ecology, laumei, pa‘a, pe‘a and other endemic wildlife flourish. But on this ocean-facing beach I find successive piles of washed up plastic and rubber junk carried by the winds and the currents. It is this great ocean continent, that makes up a third of the planet’s surface and most of its waters, which is known, among other names, as Vasa Loloa in gagana Sāmoa, Lul in Hakö, Moananuiākea in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i.

For the last five centuries, European, American and Asian strategic and commercial desires have played out in the Moananuiākea with little regard for Indigenous peoples’ agency, relationships or perspectives. Academic, Teresia Teaiwa (Banaban, I-Tungaru, African American) defines the militourist complex in multiple contexts as when “military or paramilitary force ensures the smooth running of a tourist industry, and that same tourist industry masks the military force behind it”.[1] Realities which the inaugural Ko Honolulu Hō‘ike‘ike Hana No‘eau o nā Lua Makahiki,[2] curated by Fumio Nanjo and Ngahiraka Mason, did not shy away from.

The exhibition presents a model of centring local place, local histories and local contemporary art, to in turn reach towards and contextualise the cultural flows beyond these shores. Most of the artists – local, Indigenous, settler – exhibited work critical of extractive militourism exploring colonial capitalist tropes of tropical paradise and limitless entertainment as well as the real estate poisoning of lands, waters and bodies for Eurocentric/foreign fulfilment.

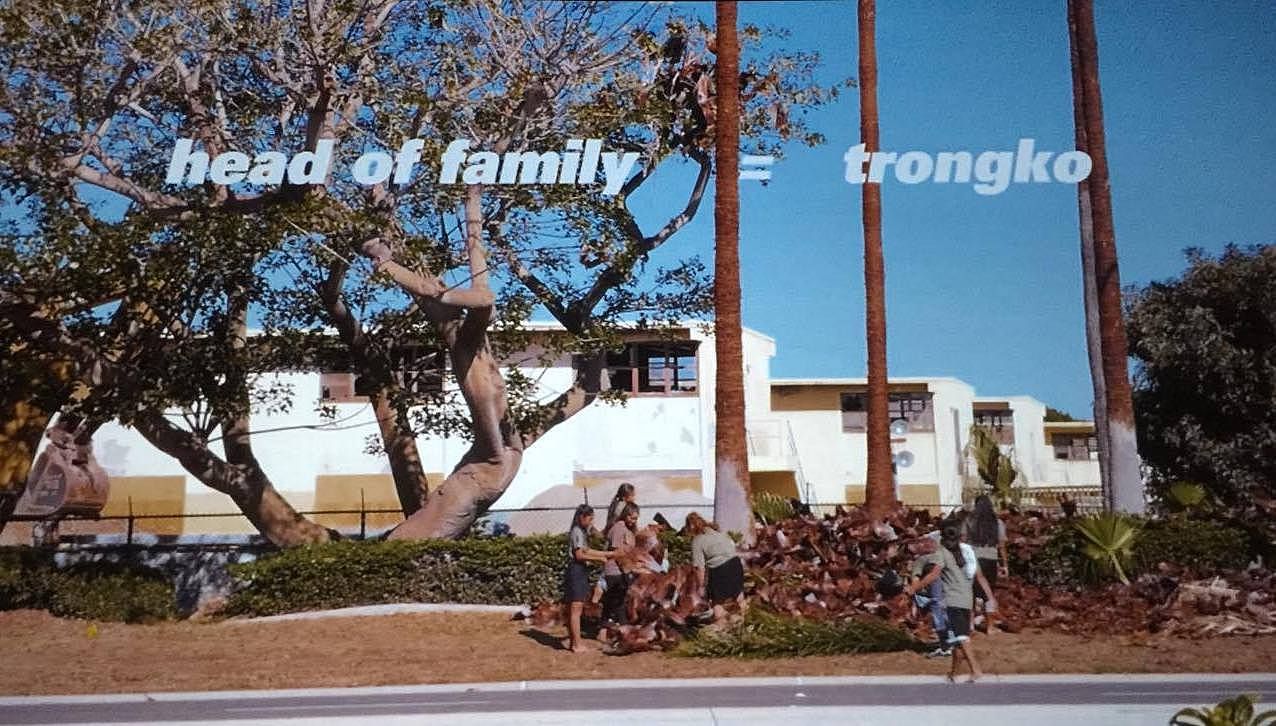

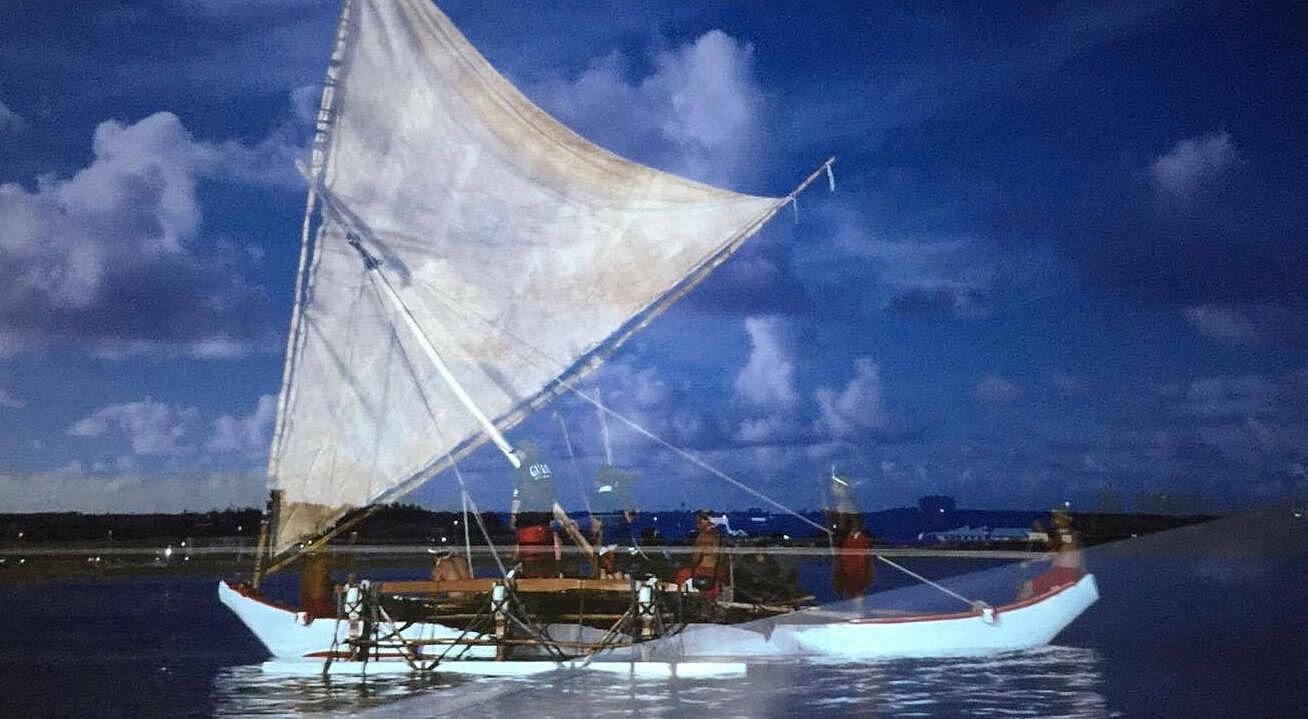

In Magellan Doesn’t Live Here (2012–2017) by Mariquita Micki Davis (Guåhan/USA), Chamorro people are able to answer back with living memory to the colonial mirage of Ferdinand Magellan’s visits in 1521. A Sakman – customary outrigger canoe – was made and launched during the 2016 Festival of Pacific Arts in Guåhan. The single-channel work highlights the anxieties around returning to ancestral homelands, and the ongoing recovery from militarised settler colonialism. Questions arise of the links between oratory and literature, revival of sacred song, dance, Sakman, maritime navigation, and Chamorro language under centuries of Spanish and currently United States colonial occupations.

The winds and currents across and through our most important ancestor, Moananuiākea, also mean the ongoing ecological, psychological and physical traumas created and continuing…do not lessen with wavering media attention.

The winds and currents across and through our most important ancestor, Moananuiākea, also mean the ongoing ecological, psychological and physical traumas created and continuing – through the nuclear tests at Bikini, Enewetok, Kirisimati, Malden, Moruroa, Fangataufa, Montebello, Emu Field, and Maralinga – do not lessen with wavering media attention. Thousands of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples from these and surrounding lands and waters continue to suffer through radiation-related illnesses and premature deaths. The impact of the radiation flowing right now from Fukushima remains to be recognised, and restorative actions are yet to be implemented.

Islands in a Basket (2017) by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner (Marshall Islands/USA) is a three-channel installation set amongst pandanus mats and baskets. The works speak to the experiences under German missionaries, wartime Japanese occupiers, and American colonisation, which inflicted the Marshall Islands with particularly devastating traumas from nuclear testing, physical deterioration and economic dependency. A renowned spoken word poet, Jetñil-Kijiner activates her politically and spiritually charged laments in arresting video works that crush island sunsets into demonic ancestral figures and atomised islander presences. The baskets each contain printed stories and mushroom cloud images that attest to the ongoing in/visibility of present nuclearised tragedy in this ocean continent.

Poetic abstractions of military training grounds imposed on sacred islands appear in Brett Graham’s (Aotearoa New Zealand) Target Island series. The fibreglass reinforced concrete shapes are positioned in a four-cornered space with a central altar. The four works – Standing Rock (2017), Guanahani (2017), Code Geronimo (2017), Target Island (2017), and Target Island 2 (2017) – pay homage to the ongoing struggles over four occupied territories. The directions of the works, “represent histories, rights, interests and subjugation of people and place,”[3] encompassing sacred territories threatened and violated by weapons testing and mineral extraction: Očeti Šakowin Oyate lands in the north, Guanahani island in the east, Apache territory in the south, and Kaho‘olawe island in the west, the latter returned to Kanaka ‘Ōiwi after decades of activism against United States military shelling of the sacred island for ‘training’ shattered its water table and ecology.

Amongst the range of works critical of military, nuclear and spiritual violence on archipelagic ecologies and the deep ocean linking them, the Biennial pivoted around communities on and off ancestral territories. Indigenous diaspora is a recurring experience due to extractive and settler colonialisms, especially in Banaba, Nauru, Kwajalein, Okinawa, Kanaky New Caledonia, Viti, Tahiti, Tuamotu, Palau, Guåhan, West Papua, Maluku, Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand and other places. In turn, whole archipelagos have already been evacuated due to rising sea levels, erratic weather patterns spoiling crops, and water tables becoming salinated amongst other impacts from external colonial impositions such as processed foods, body-shaming monotheistic religions, and individualistic capitalisms.

Ko Honolulu Hō‘ike‘ike Hana No‘eau o nā Lua Makahiki, exhibited across various sites, is presented at a time of increased visibility and exercise of Hawai‘i-based sovereignty. The unceded Hawaiian Kingdom was forcibly made part of the United States of America when American plantation owners and missionary families orchestrated the 1893 coup d’état and 1898 annexation by overthrowing the constitutional Indigenous monarchy, and the democratically expressed will of the multi-ethnic citizenry. Hawai‘i has more in common with other island contexts than continental populations fearful of difference or justice, in that complex relationships – linguistic, culinary and genealogical – bind diverse communities to each other. I look forward to future editions of the Honolulu Biennial expressed in at least three significant languages in the islands: ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, Japanese and English.

I am buoyed by the respeaking of spoken and sensual languages and knowledges banned and dehumanised by Eurocentric monolingualism and supposed Enlightenment.

Swimming in the moonlight on the eastside of O‘ahu after a dinner with local artists and curators, looking across the waters to the lights of suburbia around us, I feel beyond my own diasporic/displaced Indigenous Sāmoan body. I am buoyed by renewed relationships bypassing capitalist consumption, and the dissolving of militourist control over our bodies and worlds. I am buoyed by the respeaking of spoken and sensual languages and knowledges banned and dehumanised by Eurocentric monolingualism and supposed Enlightenment. I am buoyed by the recovery of ahupua‘a and other ways of knowing land and sea, in our relational futures and presents. We are the ancestors in becoming, the restless natives (and other islander communities with us for generations), and our sacred (is)lands are not (for militourist extraction) on the menu of late capitalism.

The 1st Honolulu Biennial, The Middle of Now / Here, is exhibited in various venues until 8 May 2017; see online dictionary Bitrevision for gagana Sāmoa translations: mike.bitrevision.com/samoan/word/letter/all; see online dictionary Nā Puke Wehewehe ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i for translations: wehewehe.org; Mahalo nui loa to Bryan Kuwada for ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i translations and guidance; the author’s travel to Honolulu was supported by the MADA Curatorial Practice program.

[1] Teresia Teaiwa, ‘Reading Paul Gauguin’s Noa Noa with Epeli Hau‘ofa’s Kisses in the Nederends: Militourism, Feminism, and the “Polynesian” Body’, in Inside Out: Literature, Cultural Politics, and Identity in the New Pacific, 1999, eds. Vilsoni Hereniko, Rob Wilson, Rowman + Littlefield Publishers, Mannahatta New York, pp. 249-251

[2] Translation into ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i by Bryan Kuwada of ‘the Honolulu Biennial’.

[3] Ngahiraka Mason, 2017, “Talk Story: Mobile Geographies,” in Honolulu Biennial 2017: Middle of Now|Here - Essays, p.6