EXTREMELY COOL PARTY DIVA: Freya Daly Sadgrove chats to Hera Lindsay Bird

The funniest poet in New Zealand in conversation with the *other* funniest poet in New Zealand about TMI, jokes, sincerity and being a true sweetie pie.

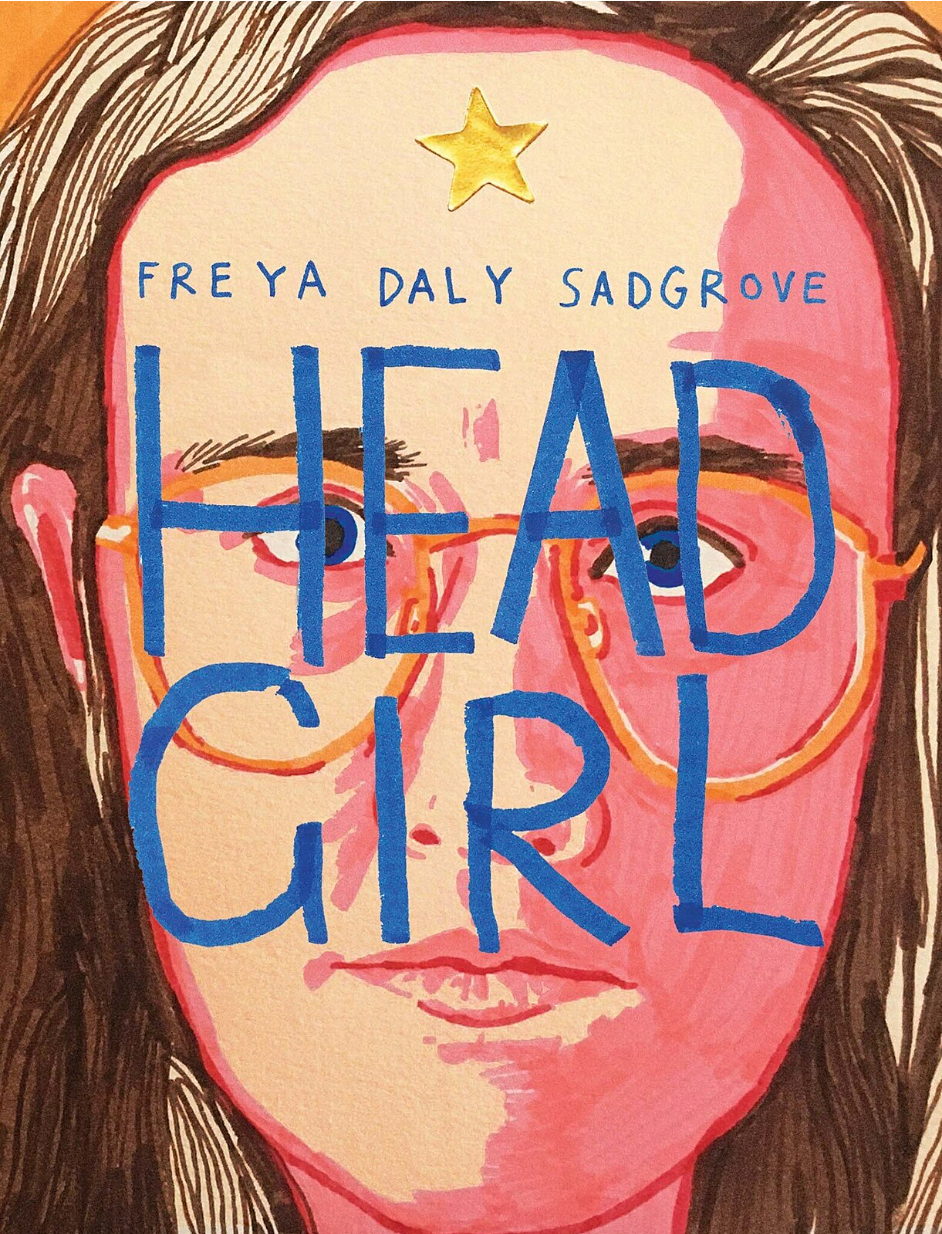

Freya Daly Sadgrove, the funniest poet in New Zealand, has just released her debut poetry book Head Girl. Hera Lindsay Bird, the other funniest poet in New Zealand, talks with Freya about TMI, jokes, sincerity and being a true sweetie pie.

FUN LOVING, FRIENDLY AND FEARLESS

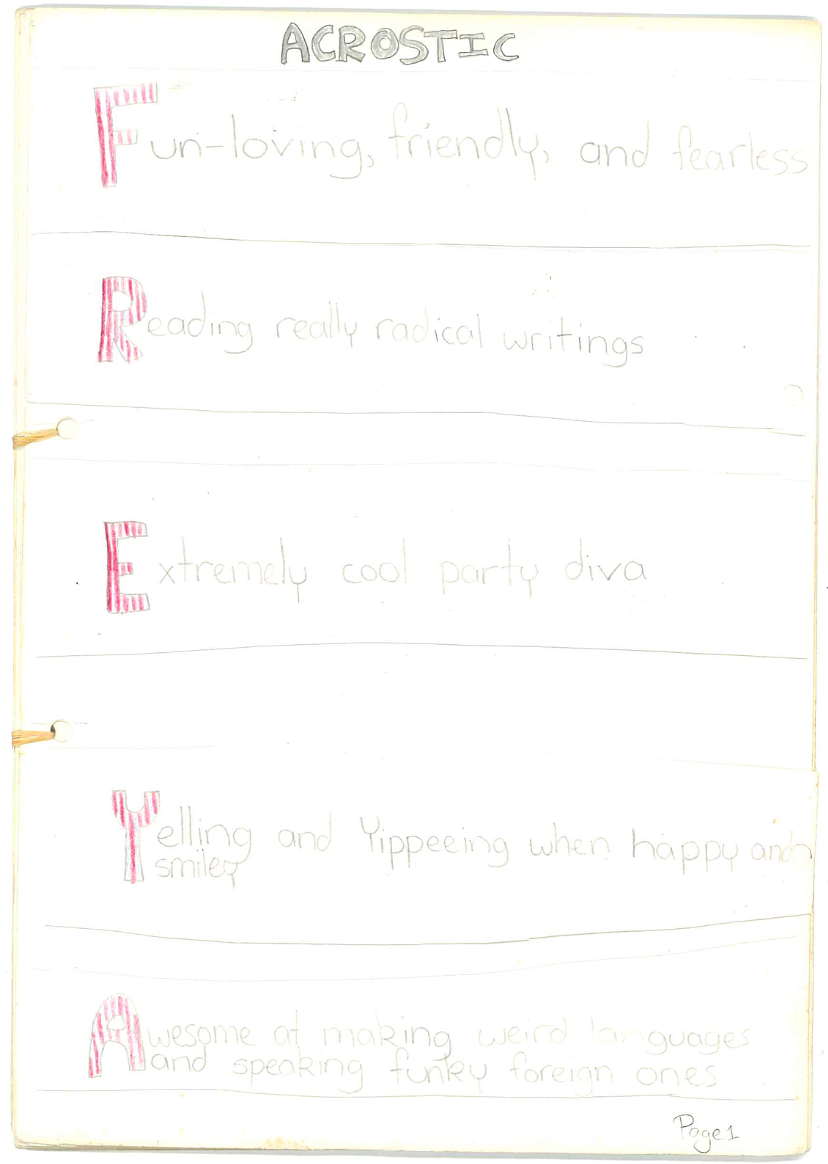

I first met Freya when she applied for a place in a summer writing workshop I was running. I was at a crossroads in my life, and had decided to go full Dead Poets Society. The workshop was called ‘TMI’ – which, for the village elders in the room, is short for Too Much Information, a joke that has come back to bite me deservedly in the ass. When Freya showed up to the workshop, I loved her instantly. She is, as the opening line of her childhood acrostic poem (reproduced below) suggests, Fun Loving, Friendly and Fearless (not to mention an Extremely Cool Party Diva AND Yelling and Yippeeing When Happy and Smiling).

In the TMI workshop, I’d intended to keep a bit of professional distance, as I didn’t want to go full Robin Williams on anyone, but within a week I was drinking wine out the back of a church while Freya played little songs on the organ. I mention this not as a way of acknowledging my own subjectivity, but simply because I want to begin by saying, I love Freya, she’s my friend.

RIGHT NOW

Right now it’s Wednesday afternoon, and Freya is on Twitter saying “swallowed my meds with olive brine just now despite being sick in an uber yesterday from drinking too much olive brine.”

Right now it’s Thursday, and I’m watching a video of Freya as a child, dressed as Santa, riding a washing basket to victory. Every year she’d write and direct a movie starring all the kids on her street, which would be screened at a the annual cul-de-sac BBQ party. In the video, she’s subconsciously mouthing everyone else’s lines.

Right now it’s Friday morning, the night after Freya and Eamonn’s book launch. I’ve come to meet Freya at her bedsit in Island Bay, which she refers to as ‘The Stables’. Her bedroom is full of juice and toys. It’s a hot day, and we sit on her roof. Big purple flowers abound. We’re talking about the events of the previous night, specifically her launch speech. Freya says, “I kept trying to write a fucking speech, and I could not fucking write a fucking speech.” What she did write, was a list of people on the back of a McDonald’s receipt, whom she proceeded to thank in an increasingly euphoric and flustered way, before yelling “I am so happy to be alive!!!”

She’s embarrassed about the speech, but shouldn’t be. For one thing, nobody comes to a book launch wanting a TED Talk. For another, a well-rehearsed and lyrical tribute would have been antithetical to her book. I don’t mean to suggest her writing is not meticulous and intentional, only that there’s a deliberate kind of recklessness and a feeling of freedom in her writing that makes it so exhilarating. Listening to Freya read is like watching a cartoon horse galloping across the desert by moonlight, and it’s only when you pause and look at each individual frame that you can see the painstaking detail that went into making it look effortless. Besides, Freya must be one of the few people who can stand on stage without a script or plan and not make the audience cringe with secondhand embarrassment. She can stand comfortably in her own discomfort and, in doing so, allows the reader to stand there with her. I don’t know how to describe it. She has a chaotic serenity to her, like one of those ancient Zen monks who used to push people into bushes in order to facilitate their enlightenment.

EATING SPAGHETTI WITH YOUR BARE HANDS

I don’t want to get into the baggage of the term TMI. We’re all familiar with the discourse. Leaving aside the question of who gets to decide what amount of information constitutes too much, and why, TMI has become a kind of shorthand accusation for literary narcissism: the compulsion to reveal things about the self in a way that gratifies the writer’s ego without consideration for the reader. As Freya says in her poem ‘If I had your baby in my uterus I would probably kill it with abortion’, “mirrors facing each other are only interesting because they’re facing each other.” But TMI also invokes the idea of the listener’s discomfort. There are certainly many moments of intentional discomfort in Head Girl, but within that discomfort lie pearls of generosity. In Freya’s work, there is no such amount of information as ‘too much’, because whatever is disclosed is always disclosed in service of the poem, not the poet. As a reader, there’s nothing I love more than encountering something I’ve always felt but didn’t know I felt until I heard someone else say it first, and Freya’s book is full of these moments.

Freya and I often talk about something I saw on the internet once. It was a Reddit thread where someone asked the question, “What’s the weirdest thing you do when you’re completely alone in the house?” Most of the answers were fairly pedestrian, but there was this one guy who said when he was alone he liked to eat all his food, including spaghetti bolognese, with his bare hands. “I honestly think about it all the time,” says Freya. “It appeals to me so much.”

There’s something I want to say about the spaghetti guy, his fists stuffed with noodles and sauce that recalls Freya’s writing to me – but I don’t know what.

YOUNG AT HEART

Sometimes when I’m hanging out with Freya I feel like we’re both Tom Hanks, in the movie Big. We talk about kids’ books and eat pancakes. Sometimes we go to mini golf. Freya and I both worked as children’s booksellers and have a deep and abiding interest in children’s literature. On the roof of the stables, there’s a mug, with pictures of Freya and some 90s superhero clip art on it, that says “Bookgirl”. When I ask her about it, she says it was a Secret Santa gift, based on her job as a storyteller for the Children’s Bookshop in Kilbirnie. Bookgirl was her alter-ego. Her slogan? Bookgirl: the girl with the power to read books.

Freya’s bookshelves are filled with children’s novels. There’s a huge stack of Diana Wynne Jones on her desk, which she’s borrowing from Elizabeth Knox. She makes me read the entire first chapter of The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone by Jaclyn Moriarty while she plays Spyro the Dragon, heartily whacking moles with a virtual mallet.

Later, when we’re talking about therapy, Freya says, “I love to visit the past. It’s easy to visit the past if you keep a good record of what’s happening inside your brain during it. I always think about that bit in Howl’s Moving Castle where the Witch of the Waste’s curse is catching up with him, and part of it is “tell me where all past years are”, and he’s like “I know where all past years are, they’re right there, I could go and play bad fairy at my own christening if I wanted.” I think I could do that too. In fact I kinda wanna write a book that is slightly for children about something very much like that that happened inside my imagination during therapy, so that’s also a way that therapy has impacted my work.”

I’ve been so mean to myselves for ages.

The idea that Freya might someday write kids books seems inevitable to me, but when I ask her about it she says, “I definitely want to write for children and I always have, but I’ve never been kind enough. You have to be so kind to write for children, and part of that is being kind to yourself, to all of your selves throughout time, and I’ve been so mean to myselves for ages. I think I’m much much closer to embodying the kindness that writers for children have to have than I’ve ever been before, so hopefully that means I can start working towards that in, I don’t know, the next few years. I’m not in a huge rush. I’m also interested in the idea of writing poetry for children actually… I had this book of poems when I was a kid called Candy and Jazz – Candy was a girl and Jazz was a cat – and it was so… fuckin cool and strange. I have no idea where the fuck it came from. It was the kinda book that seemed like it coulda been thrown through from someone on the other side of the mirror to land on my bedroom floor.”

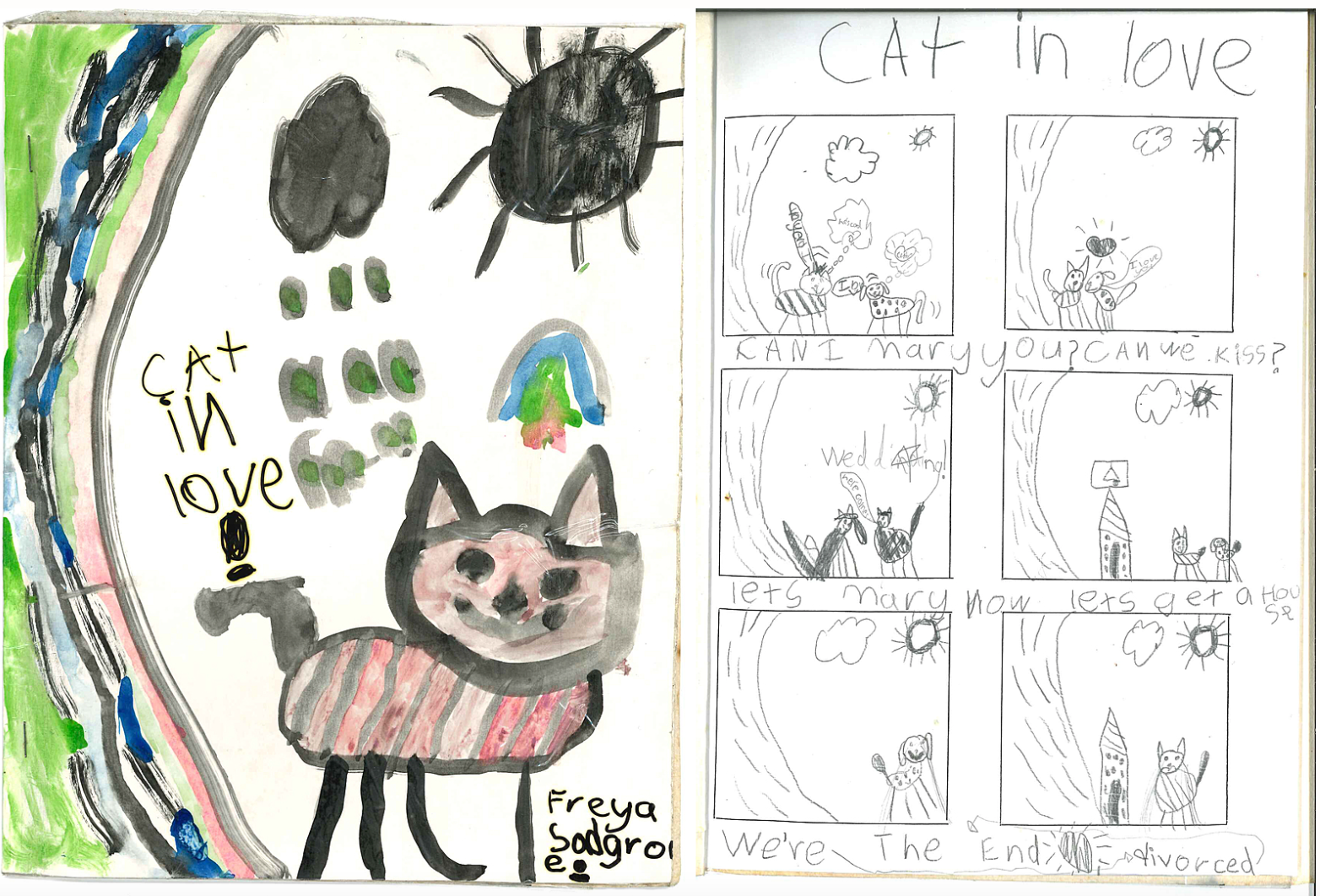

Freya shows me some of the first ‘books’ she ever wrote – a hand-stapled booklet of poetry, which she precociously titled Freya’s Mad & Thoughtful Poem Anthology. Ox, a mutual friend, says, “I bet u thought u were fucking smart calling it an anthology lmao,” which Freya fully concedes. One of her most amazing personal artefacts is a comic written after her parent’s divorce called ‘Cat in Love’ (reproduced below). It’s one of the most tragic and unintentionally satanic things I’ve ever read. Part of Freya’s motivation for writing these books was the success of Laura Ranger, a famous New Zealand child poet from the 90s, who published a book called Laura’s Poems, complete with Bill Manhire endorsement. “I was so fucking jealous,” Freya says. “I was like, ‘Who is this girl? Something’s not right here. You can’t just be a kid and publish a book.’”

It occurs to us that, like Laura Ranger, we both have portraits of ourselves on the covers of our books. There is clearly some deep-seated psychological stuff going on. Freya even considered titling Head Girl Freya’s Poems but decided it was too niche. She can still recite Laura Ranger’s most famous ‘Two Word Poem’ by heart: “The toad sat on the stool; it was a toadstool. Fucking great, Laura. Not over it. Jesus Christ.” We laugh and laugh.

ANECDOTAL

“When my parents split up when I was six, I realised that Love Ends, so I had to break up with my sweet boyfriend Harry, who had been my boyfriend for fully ages. We even kissed and stuff, disgusting. Anyway we were at after-school care and I was like, ‘Harry, come with me’ and I led him into the empty church hall next door, and I made him stand at one end of the hall and I went and stood at the other, and I was like, in ringing tones, ‘Harry, we…………….are breaking up.’ It was a beautiful ceremony. Embarrassingly, I do reference that in a poem. Man, can’t tell any of my cool anecdotes anymore cos I used them all up in my fkn book.”

DNON’T FORGET DALY, SAYS FREYA: “DAD

ACCIDENTALLY ON-PURPOSE PUT MUM’S

LAST NAME IN THE LAST-NAME BIT ON MY AND MY SISTER’S BIRTH CERTIFICATES, INSTEAD OF THE MIDDLE-NAME BIT

YOWZA!”

“And Daly is pronounced Daily. Idk! Who really cares. When I was a kid I never put Daly in, but then I became a feminist.” – Freya

SWEETIE PIE

No matter how much of your personal life you reveal in a book, the idea of poet as confessor should always be taken with a grain of salt. We talk about performative honesty, and how even if your goal is absolute personal transparency, there’s still a curatorial aspect to representing the truth. When I ask Freya about any conspicuous absences in her book, she says, “Idk, this is super interesting, in an interview with Lynn Freeman she said she felt like she knew me after reading the book, and I was like, ‘cool!’ And then later I was like, ‘wait!’ Like, I’m desperate to reveal everything, I want no truck with mystery, and writing poems about some of my more horrible thoughts and feelings has felt like what ‘revealing everything’ must be. But then at some point it’s like, maybe every choice to reveal something very personal about myself in a poem just obscures something else. Cos I suspect that writing about all the nasty things inside me probably somewhat obscures how muthafuckin cute and sweet I am. I’m like, really nice, and when I experience joy I really really experience it, you know. I felt the need to tone down my… my inner sweetie pie in Head Girl in ways that I did NOT when, for instance, I wrote my MA.”

APOLOGETIC

In my launch speech for Head Girl, I mentioned that two of the most overused reviewing buzzwords are ‘unsentimental’ and ‘unapologetic’. Freya’s work is neither of these things, and honestly thank Christ for that. Her work is dangerously sentimental and ruthlessly apologetic, even though in her poem ‘No One Will Ever Be Your Bud if You Are Not Your Own Bud’ she says, teasingly, “We’re such good feminists we keep our apologies to ourselves.”

“I was really stoked in your launch speech when you said I was ruthlessly apologetic, cos I always think about that – people fully do go on about fkn ‘confessional’ poetry or whatever being unapologetic and ‘unflinching’ and I was like someone better fuckin pick up on how much I’m flinching or I will be pissed. So thank you. I thought I would never be able to read ‘Turducken’ aloud, but now I’ve done that twice and people haven’t got too mad at me for making that particular suicide joke that’s in there. I definitely thought I wouldn’t be able to read ‘I’m So Mentally Strong It Moves Me To Tears’ aloud ever, but then there was an event at NYWF last year called ‘Can I Laugh At That?’, which was specifically for us to say our most upsetting jokes. I’ve never shaken so violently in front of an audience as I did during that event.”

DEPRESSED, BUT THRIVING

At Freya’s book launch, she told everyone that she’d just had her last therapy session that morning. Her therapist was even in attendance at the launch, which should tell you something about the kind of patient Freya must be. I asked Freya about the relationship therapy had to her work.

“Mainly the impact of therapy on my writing has been to do with how it… facilitates my thought processes. I have lots of thoughts and they can get quite loud and fast, and in therapy me and this cool lady get together to sort them all out, and it means I get to look at them all from interesting and revealing perspectives, and that’s poetry baybee. I don’t know, I need to get my therapist over here to help me know what I mean.

Some of the saddest poems in the book might have turned out joyful AF if I hadn’t felt so deeply ashamed about being in love when I wrote them.

“My depression did most of the job of dulling my enthusiasm for life for me, but I do get pretty embarrassed about some of the cuter feelings I have. Like I’m super into bumblebees and shit. Plus… I love people very very much, and I wrote a lot in the book about being in love with someone who wasn’t really prepared to accept my particular affection (i.e., too much of it), so partly I had to cover love up with snarkiness and jokes and barbs, and partly some of the horrible things I say about being in love are actually just what happens to my thoughts when I try to censor my feelings in the first place, before I even write the poem. Some of the saddest poems in the book might have turned out joyful AF if I hadn’t felt so deeply ashamed about being in love when I wrote them. Lol sad.”

GAP-TOOTHED

One of the most striking things about Head Girl is how similar Freya’s IRL voice is to her poetry. This might seem like an obvious and trite observation, but writing in your speaking voice can be an immensely difficult thing to achieve, which goes some way to explaining why most poetry is almost tonally indistinguishable. Obviously, it’s not everyone’s goal to write the way they speak. It’s not mine, but then again I’m no good at speaking, whereas Freya’s use of language, on and off the page is a constant source of delight. To me, one of the exciting things about poetic ‘voice’ is the opportunity to feel like you’re in the untranslated consciousness of another person. Freya’s ‘voice’ is apparent in her poetry, not only in her phrasings and her idiosyncratic word choices, but in the punctuation and spacing and grammar. I asked her how she achieved this.

“My poems started getting gap-toothed near the end of my MA. (Chris Price called them gap-toothed, so I always think of the lil gaps in my poems as gap teeth. I am always saying to my poems ‘I’m sorry I called you a gap-toothed bitch. It’s not your fault you’re so gap-toothed.’) I found the gaps a really useful way to essentially do comic timing on the page. I mean you do this with your ellipses, right? I love ellipses. They’re like little comedy drumrolls.

“Anyway, I don’t know, it took me a while to figure out how I wanted to do it, and I think I’ll change heaps in the future. But it’s definitely important to me to sound like myself. You know how everyone has a poetry voice for when they read their poetry aloud? Their normal voice gets a bit more high-brow and a bit sexier or something? I kinda hate that, but it’s impossible to avoid. I try to enunciate good when I read, but I also try to keep my voice from going off the deep end too much into ‘I am a poet smoochy smooch smooch,’ and therefore it is necessary to keep the writing itself from doing that. Like when you have a script, the success of a script relies heavily on how you deliver the lines…. I feel like in my poems I am trying to do the script and the delivery at the same time, and that’s a fun puzzle for me to play with.”

RACONTEUR

I ask Freya to tell me a joke:

“A two-year-old used to tell me this one and I still think about it a lot:

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Knife

Knife who?

Cut off your face with a knife!!!”

OH MY GOD, GET A SHORTER NAME ALREADY

VERY, VERY COOL GIRL

EVERYTHING MATTERS!!!!!!

Freya’s book is called Head Girl, taken from the title of one of her poems, ‘I Used To Be Head Girl of my High School and Now I am a Massive Cunt’. I’ve never met anyone outside of an Enid Blyton novel whose ambition was to be a head girl. I asked Freya why she cared, and what relationship, if any, giving rousing speeches to an auditorium full of teenage girls in blazers had to do with writing. She said:

“The impulse to stand on stage and give rousing speeches to girls in blazers is probably the exact same urge as the urge to write poetry. Like, now that you’ve said it, I absolutely can’t separate the two in my head. Gawd, I really did wanna be head girl so bad. I don’t know why it felt so important, I just clocked it as an ambition when I was in year 9, and for some reason it also felt possible. Which is kinda weird, it’s a weird goal to have, like, ‘In five years’ time I wanna do a big speech to a large group of people about how much the five years will have meant to me.’ I suppose it’s like poetry in that I just want to say everything, I just want to explain everything, I want us all to explain everything to each other, everything we think and feel, and also how we are thinking and feeling it, like, what exactly is going on in each others’ brains, how are we all going with experiencing the world as individuals, let’s have a little check-in, and then another check-in from a weirder angle so we can see it weirder, which is to see it clearer (and sometimes you can do that with jokes), and I want for it all to matter, for everything to matter, and I just want us all to take note of the fact that it all matters. And so any opportunity I can get to stand at a lectern and be like ‘Everything matters!!!!!!’ I will grab by the absolute balls. Writing poetry is just the girl in a blazer in my heart making a speech to the girl in a blazer in your heart. Everyone has a girl in a blazer in their heart and I wanna CONNECT with them all in MEANINGFUL WAYS that make SCHOOL LESS DISTRESSING TO ATTEND.”

Head Girl is published by Victoria University Press

Feature image: Freya Daly Sadgrove, photograph by the Book Council / Read NZ