An Umbilical Cord that was Never Cut

South Sea Island artist Jasmine Togo-Brisby reflects on growing up a descendant of ‘people-stealing boats’, the vessels that have become artistic material.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

CW: South Sea Island readers are advised that this article contains images and voices of deceased persons. Readers are warned that there may be words and descriptions that could be culturally sensitive and which might not normally be used in certain public or community contexts.

Earlier this year I took my daughter Eden on a three-hour glass-bottomed-boat tour at Te Whanganui-A-Hei (Cathedral Cove) Marine Reserve. Pathetically, I got seasick from looking down at the marine life through the glass window in the bottom of the boat. It was a particularly rough day – we had been booked to go the day before but it was cancelled due to extreme conditions. The movement of the water was relentless, pushing against the little boat as though to eject us from the sea. I sat there trying not to throw up, trying not to let Eden see that I was in absolute misery. I forced my eyes to the horizon and wished the time away.

I thought of my ancestors.

Three months

Darkness

Movement

Sickness

Stench

It’s inconceivable. The ship packed full of damaged and sick bodies, strangers from different regions, sharing in the suffering together, language muted, thrown into a melting pot in the belly of a ship. The ship is an abyss, the initial space of rupture, the bringing together of many nations and tribal groups, which would otherwise be disconnected, now into a new, shared entity. In that bondage birthed a new culture, a collision of cultures – some aspects adopted, others lost – that would ripple down the generations.

Like many other creation stories, ours started in darkness, but it’s different when your genesis is at the bottom of a ship. My mother says, “we are floating”, adrift... in both time and space. We are Australian South Sea Islanders, the Australian-born descendants of the Pacific slave trade; the movement of our people is a jarring juxtaposition to the free migration of other Pacific peoples, most of which is centred on fearless ancestors navigating sophisticated voyages across vast stretches of open sea on waka, not restrained on colonial ships.

Our South Sea identity is complex and often difficult to understand: we identify as Blak, in a part of the world where Blakness often means Indigeneity, and while we have a kinship and intermarriages with our First Nations brothers and sisters our South Sea bloodlines are not Indigenous to Australia, nor are we often regarded as Indigenous to our island homelands either. We are a Pacific slave diaspora, formed in the holds and on plantations, an identity often too alien to comprehend. Displaced and disenfranchised, for those of us in the afterlives of slavery, the journey is genesis.

'Centre Flower no. 335', 2020. Backlit film, aluminium lightbox 1250 x 1250 x 150mm. pc. Ryan McCauley.

The late Auntie Faith Bandler speaks on the stories she grew up hearing from her father about his abduction at the age of 13, in 1883:

When he was kidnapped and taken in the boat by the slavers and what it was like in the boat coming over from his island Ambrym, in the New Hebrides and how rough it was. And how they were all held in the hull and how sick they were, and those who died were thrown overboard … another world, another world.

Another world. A nonworld. The middle passage, a world of gratuitous violence, of transportation and transformation, the unimaginable and unknown. The ruptures caused by the vessels are held in our collective memory, for both those who disappeared over the horizon and those who mourned them on shores. The trauma of loss and longing reverberates through the generations.

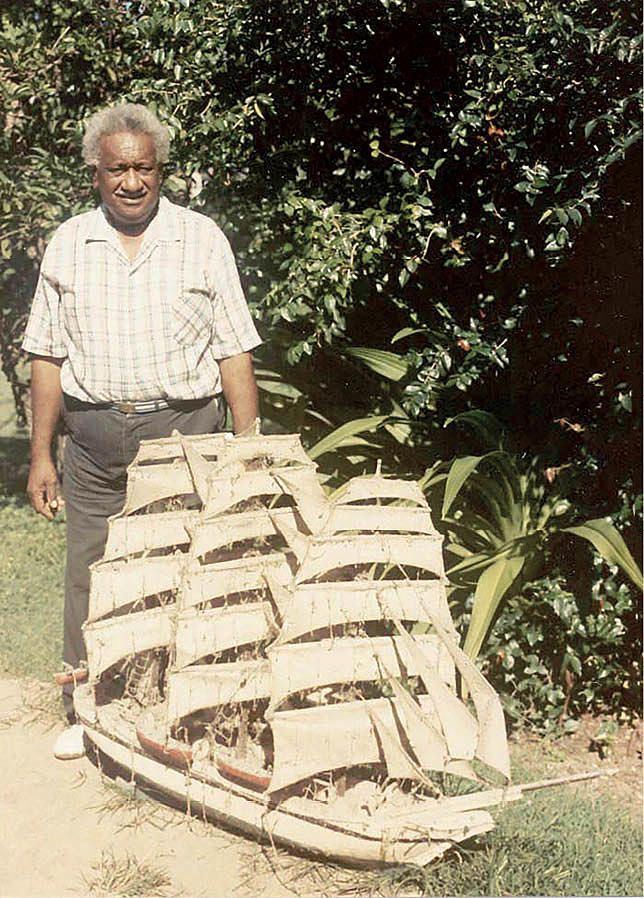

I think of Uncle Jack Marau, a South Sea man who handcrafted a model replica of the vessel that took him on the journey that he would never return from. Unfortunately, there is little to be found on his life; this image floats within a sea of numbers (our ancestors’ bodies as figures), ‘facts’ and trade routes compiled by the historian who captured the image. All I can do is imagine what this act of making was like for him. How his body was compelled to expel and release the things that cannot be or haven’t been spoken about, for which there aren’t enough words or the right words or the right language. Uncle Jack’s ship is a radical act of reclamation and resistance – in a time when Australia was trying to eradicate our people through mass deportations (the largest in Australian history), Uncle Jack made the intangible visible.

Christie Fatnowna with a model ship made by Jack Marau, 1988. Jack Marau lived with Norman and Hazel Fatnowna in his old age; they inherited the model ship when he passed away. Source: Clive Moore Collection

The act of reclaiming the vessel can also be seen in our cemeteries; the Mackay, Queensland, cemetery in particular holds a headstone that takes shape as the hull of a large vessel. It is adorned with sugarcane and complete with a large anchor, said to be an original from the ship that transported them to Australia. In their departure from this world, they proudly insist on being seen.

With many of our people not buried in cemeteries, but in unmarked graves amongst the cane, I respectfully see this headstone as more than an individual memorial. Its size and symbolism represent monument and memorial for many. It reflects the Wantok (one talk) phrase “yu me two fella one scoon”, meaning both people shared the journey on the same schooner to Australia, and used as an expression of union beyond kinship.

Unmarked Australian South Sea Islander graves at the Mackay cemetery (ABC: Sophie Kesteven).

When I was growing up, the village elders would talk about the sailing boats. They would call them ‘people stealing boats’ or ‘steal ships

I look to our islands, where the representations of the vessel can also be found in the kustom of repatriating South Sea families to our ancestral homelands. The South Sea family is wrapped between palm fronds, which create the shape of a ship; they then walk with the ship draped around them back into their village, where they are welcomed with singing and celebrations of their return. Both the tombstone and the ceremony can be viewed as modes of return, a hope that perhaps if we retrace our steps and reboard the vessel we may attempt recovery – to reclaim what was lost/stolen, either in this life or the afterlife, to make our way home to the motherland.

On my ancestral homelands of Vanuatu, in the wake of the ships, the people of Tanna continue to fear the ocean, and are often not allowed at the beach by themselves for fear of abduction. On Vila, commemorative re-enactments of blackbirding abductions take place: a big truck is dressed in the appearance of a ship, it drives slowly through the main street and locals onboard play the role of slavers, grabbing young men and children off the street and pulling them onto the vessel, parents run after the ship screaming and crying for their abducted children. Ni Vanuatu political figure and poet, the late Grace Molisa, writes, “When I was growing up, the village elders would talk about the sailing boats. They would call them ‘people stealing boats’ or ‘steal ships’.” The memory and trauma of the slave trade is passed down through stories and songs on the impacted islands. The women of Pentecost perform a dance and song that laments the theft of our people. As part of the ritual the women hold wooden rods with miniature schooners on the ends, they dance and push the schooners in the air, chanting:

the ships stole our people

and we don’t know where they have gone

the ships stole our people

and they've disappeared

The image of a ship invokes fear and is used a warning sign, as an act of remembrance, yearning for those who were taken; it is a practice of care, a plea to not forget a past that has not yet passed.

The Don Juan was the first vessel, taking 67 of our people from Vanuatu to Queensland in 1863. While there are records of South Sea Islanders coming to Australia as early as 1847, the Don Juan triggered the influx of South Sea Islanders – the more than 62,000 labourers ‘contracted’ to work in Australia – that would continue until 1904. For South Sea Islanders, the Don Juan is the marker of our time in Australia, of our ancestors’ journeys and struggles, of our endurance, it is something we celebrate and commemorate.

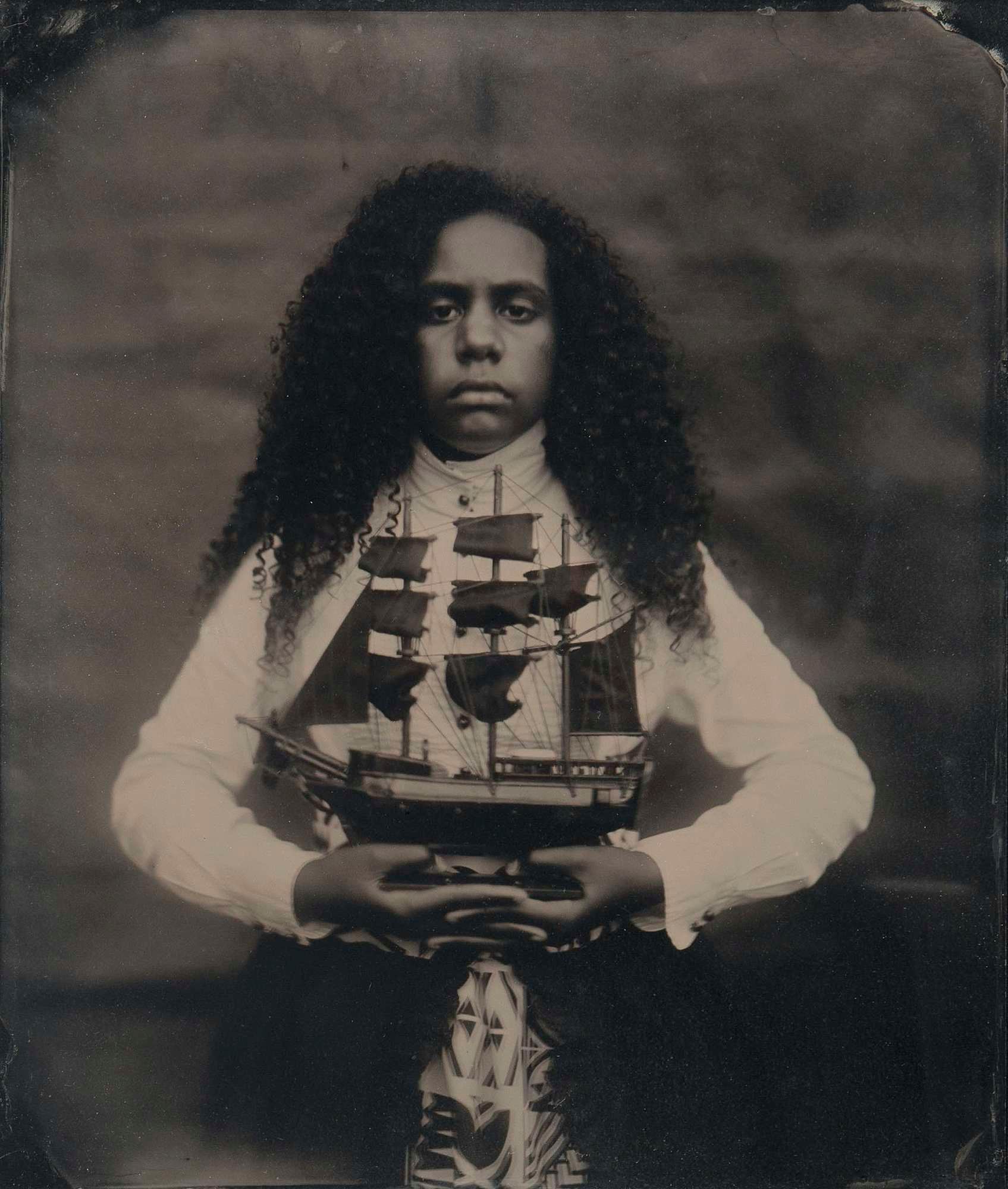

Inheritance, 2019. Collodion on glass 258 x 305mm.

I had never given much thought to what happened to the ships that once carried our ancestors; in my subconscious I assumed they had all disappeared, sunk to the bottom of the ocean, burned, you know, things that happen in movies from a time that I have never lived. So to discover that the Don Juan still exists on this earth was beyond shocking, and furthermore it is just a short flight from my home here in Aotearoa. It sits just below the surface of the water in a small alcove on the coast of Kōpūtai (Port Chalmers). Just metres from the road – locals drive past daily – there is no plaque or signifier, it’s seemingly deemed irrelevant.

On my first visit to the Don Juan I was (and still am) in disbelief. It is surreal, I shouldn’t be able to see it, it should be further away from me in both time and in space. I thought, “This is a crime scene! Why is there no police tape draped around it? This is evidence! Why doesn’t anyone care?” A question I don’t really want to hear the answer to. What I do know is that this is a painful site of memory for us, and something that I truly cannot find adequate words to describe.

Tidal Transitions.

I was told that the ship was once a water playground for all the children in the area and that hundreds of pairs of shackles were retrieved from its hull. The nearby Maritime Museum holds one pair and the Auckland Museum has another, but most were taken by collectors from the region. The main audience for both the shackles and the Don Juan is tourists disembarking from cruise ships. Their leisurely, free movement a paradox to the slave ship carrying stolen bodies across water.

The first time I took my mother to visit the Don Juan we stood on the edge of the road, looking out across the bay, in silence. We watched the surface of the water go from still, clear glass to what looked like tiny dancing ripples and swirls gliding across the bay – they danced into the shadows of the ship, where they stayed. My mum turned to me and said, “They’re talking to us.” We went back to silence, our bodies paralysed, and our eyes fixated on listening to a language that is not of this world.

These vessels are an ever-present part of our culture, we are tethered to them, and them to us, like an umbilical cord that was never cut.

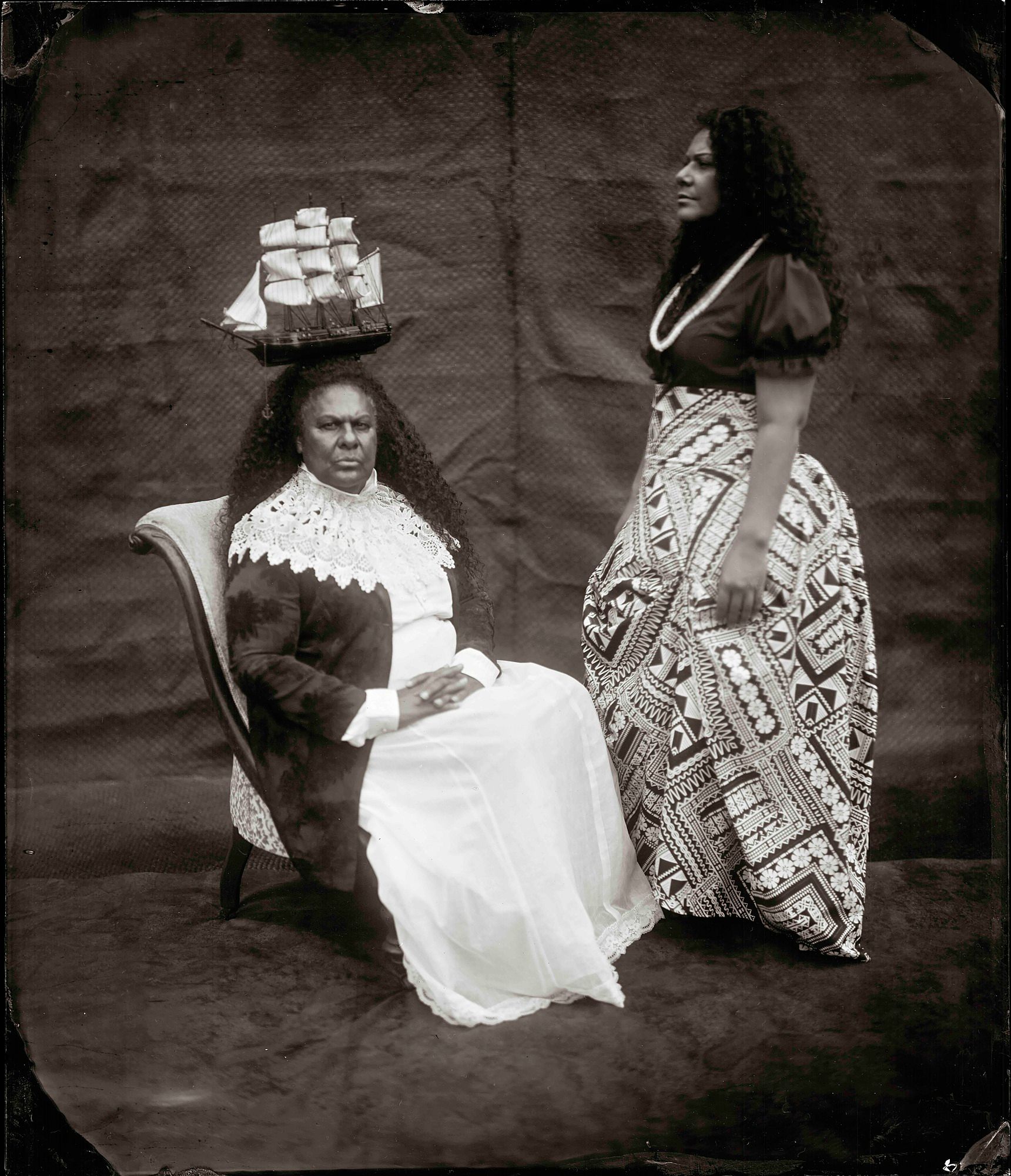

Mother Tongue, 2020.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photograph supplied by Jasmine Togo-Brisby