The Whole Sorry Lot

Joe Nunweek on regret, contrition and what we expect out of our leaders.

The 9th Floor (first an RNZ podcast, now a book) is a seminal effort in documenting NZ political leadership. Joe Nunweek admires the form, but is left shaken by the substance.

At her party’s AGM on 16 July 2017, Metiria Turei conceded to both her party faithful and the wide and cruel New Zealand heartland alike that she’d told a lie, circa 23, to keep her life under control and her daughter fed. She wrote to the Ministry of Social Development the following day confirming a confession of fraud, offering co-operation and the willingness to pay the money back. When the story compounded a fortnight later, because she’d registered to vote for a joke party from another address, she acknowledged she had to be accountable for her actions, and that she’d give up her long-stated aim to be a future Minister of Social Development as penance. When she stepped down, it was in the face of the most moral indignation and opprobrium a significant parliamentary figure has received in a generation. As Giovanni Tiso wrote on this site last week, "there is no public life, let alone a political life, that can withstand that kind of interrogation and still lay claims to honesty and truthfulness".

Deeply weird and elongated tone poems to political savvy have prescribed what she should have done differently, but the price Turei paid for her disclosure seems pretty considerable. Nevertheless, pundits and rivals remain furious. “There is still no contrition,” howled Mike Hosking/John Armstrong interchangeably, about an individual who voluntarily went to government investigators without legal advice. “When you are a lawmaker, you have to be very clear about when what you’ve done in the past has been right or it’s been wrong”, explained likely future PM Jacinda Ardern. “Her revelation wasn’t a mea culpa,” warned Damian Grant (all these commentators like their smattering of schoolboy Latin a lot).

Whether your reading of Turei was that she was contrite or defiant (and honestly, she walked a considered path between the two - people like us heard the version they wanted), the message is clear - we really, really want our leaders to wallow in penitence for their mistakes. Except for when they become deified enough. Then we don’t.

The 9th Floor (released earlier this year as a podcast series by Radio New Zealand; set to come out through Bridget Williams Books transcribed and expanded in early September) is a mammoth achievement on its face value – a series of interviews with five living New Zealand Prime Ministers that are both well-wrangled and well-edited. In a climate that’s weirdly ahistorical at the best of times, it partially traces the arc of how we got here just in time for election season and throws our current campaign and its priorities into context.

It’s also full of dozens of infuriating and tone-deaf moments on the part of its subjects. Although interviewer Guyon Espiner is at pains not to seem like some gibbering fanboy, offering some gentle push-back at times, the decision has been made to let Geoffrey Palmer, Mike Moore, Jim Bolger, Jenny Shipley, and Helen Clark speak for themselves.

Accountability and empathy aren’t always easy bedfollows, but how and when politicians exhibit either is worth scrutinising ahead of an election. Blame, regret, shame and how you live with consequences aren’t fun processes to experience or tease out, but they’re meaningful, particularly where people have sat at the extreme end of power, control and influence.

All five reigned over difficult times, when executive decisions led to even more difficult times for many communities, families, and individuals. Indeed, the experience of those Turei spoke for on the then-Domestic Purposes Benefit can be reflected on through their governments’ actions and their statements. It was a harsh environment in which Palmer and Moore’s mob set the scene for welfare reform, Bolger and Shipley’s enacted cuts, and Clark’s rationalised them.

Can you use The 9th Floor to reflect on Turei’s plight as a public servant called on to acknowledge and atone for the past? Not so much. Accountability and empathy aren’t always easy bedfollows, but how and when politicians exhibit either is worth scrutinising ahead of an election. Blame, regret, shame and how you live with consequences aren’t fun processes to experience or tease out, but they’re meaningful, particularly where people have sat at the extreme end of power, control and influence. But those who expect to divine them from the statespersonlike murmurs of these semi-retired dignitaries will come away disappointed, if not radicalised.

There’s a disclaimer throughout, of course. All five subjects frame a lot of what they did and why in the wake of the years Robert Muldoon ran the country (1975-84). It’s an interesting and consistent doctrine of necessity that leaders from Key onward won’t really be able to lean on in their memoirs – in these flashbacks, the country was always on the brink (Clark compares us to Albania, a country where dissidents were routinely tortured and killed by the government. Others simply complain that you needed…an import license to import things.) Policies and reforms simply had to be enacted. Where there’s a glimmer of agency involved, all five leaders invariably did the right thing.

In a few tender moments, there’s humiliation and loneliness and grief. But there’s never a meaningful mea culpa (there we go) or recognition of the harm their decisions caused. These people are haunted, all right – by cabinet back-stabbings, or bruising election losses – but not by the consequences that hollowing out entire sectors of the economy, or cutting benefits, or the largest land grab in 160 years might have had.

Palmer, up first, makes for a convincingly reluctant Prime Minister. He was a consensus candidate in the truest sense of the word, selected to broker peace as his government set about open trench warfare amongst itself, before he was rolled at the first sign of panic. In retirement, he’s been indulged as a bit of a constitutional law bore more concerned with process than substance, a long road that crystallises here as he proudly attests to being practical rather than ideological (a summation that could also apply to Muldoon, of course).

Indeed, it’s easy to lapse into seeing Palmer as some fussy technocrat adviser rather than, you know, a Cabinet member and Prime Minister – so distasteful are those around him that went too far, so many of the whiplash changes of the 1984 Labour government the inevitable by-product of a three-year term limit. “We had to take some drastic economic action,” he insists, “and get the runs on the board.”

Faced with Espiner’s argument that his government’s first vollies – the introduction of GST, abolishing many subsidies and tariffs in one great jolt, corporatising state owned enterprises which subsequently culled tens of thousands of jobs – served as an ambush on those who voted them in, he demurs then defers. Again, “the government was between a rock and a hard place”.

Elsewhere, his statements about the Fourth Labour Government are shaky. Much is made between Palmer and successor Moore about how they never cut the benefits, a sort of hyper-literal half-truth that skates over 1990 budget changes that would have withdrawn access to the unemployment benefit for most recipients under 18, expanded the penalisation of solo mothers who couldn’t name the father of their child across multiple benefits, and introduced stricter work tests and information-sharing across the board (Labour was defeated heavily before their amendments would have taken effect).

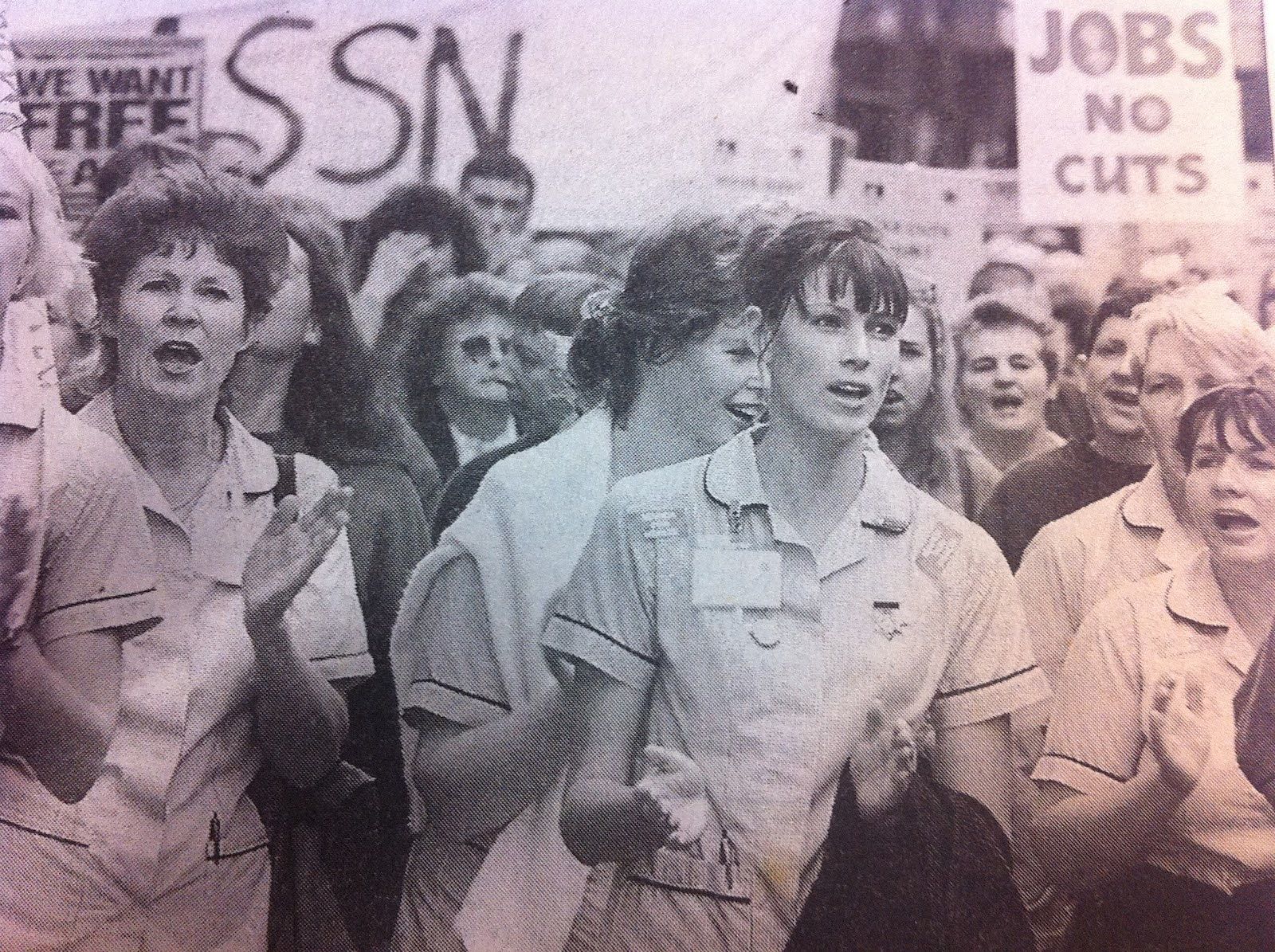

Moore, apparently in ill health, gets an indulgent hearing here, big on war stories about the late David Lange’s taste in cars and secretaries, big on talk on how the PSA and the nurses (and their majority-woman memberships) were never real unions. Elsewhere, he’s quick to even out the blame for the 4th Labour Government’ unpopularity, implying that caucus and rank-and-file alike “knew what was going on” and weren’t ambushed by its biggest reforms. He chestbeats about how his government never cut education, a statement that also aims for a kind of truthiness alongside the rapid introduction of tuition fees (which rose by an extremely nice 969% in 1990).

Echoing Palmer (but mixing metaphors lethally), he laments how “the biggest misjudgment was time…we went too fast. A lot of people lost their jobs…the roundabout wasn’t fast enough” Only to recant: “We didn’t have a huge upheaval, it’s a manufactured history.” But that’s a long and smooth view of history that doesn’t evaluate, victim by victim, the social and psychological impact of a doubling of unemployment in the three years to 1990[1], with precious little support for retraining and reskilling on the other side. It’s a diffuse sort of harm that Moore (or anyone) might struggle to truly feel. Nevertheless, it happened, and continued to happen even after his government was consigned to electoral oblivion.

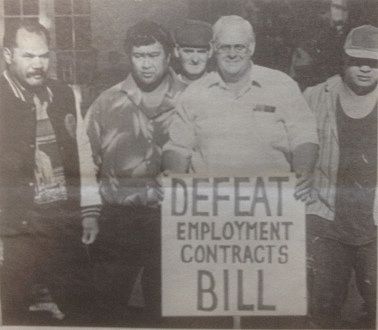

Bolger has a twinkly grandfatherly façade to his steel, and made the podcast’s biggest headlines in April when he pronounced that neoliberal policies “have failed to produce economic growth…and what growth there has been has gone to the few at the top.” In the context of the interview itself, it’s maddening. As in the hands of an angry first-year political science student, Bolger’s brand of neoliberalism is a thing…out there…being terrible. It’s absolutely discrete from the “pragmatic policy to address an issue” enacted under his aegis – the welfare cuts that slashed the after-tax income of households on the benefit to half the average wage[2], the drastic loss of job security and union density after the Employment Contracts Act, the reform and sell-off of state housing.

When asked if these have had longitudinal effects, he kicks the can. “It’s ridiculous to say that policies followed in 1990 are having an effect today…if that were so there have been another 20 years in which to rectify it.” Bolger isn’t as long-winded on leadership as his successors, but he’s adamant that “you have certain values that are important to you, otherwise you just flip-flop around the place.” But he’s powerless when he’s actually asked about the immiseration of the time, arguing that he made it as fair as he could (the exception to this is his backbone on Māori issues, where it’s clear he and Doug Graham stood firm against belligerent majority views in their caucus).[3]

Shipley is perhaps less complicated, in part because she remains a true believer in the reforms Bolger wants to hover at arms’ length from. “That’s what leaders do – take power,” she explains helpfully about her taking power. “We knew we were making a fundamental change to people’s expectations, and that’s what leadership is about.”

Ever the clear-eyed ideologue, she’s the one ex-PM here who treats the suffering as feature rather than bug, as a character-building transition to something greater rather than some adverse consequence of structural reform. “If you’ve got assets, why don’t you use those before you ask your neighbour? If you’ve got money in your pocket, use that before dipping into someone else’s.” Around the time Turei would have been putting herself through law school in the pit at the base of Eden Crescent, Shipley met a young mother out on the trail once, who thanked her. “(She) decided to go back to study. (She) took personal action that would deliver change.”

Though most of us should be so lucky to own and channel our feelings of regret – over our cruelty in relationships, our weakness under peer pressure, the times we weren’t brave, the times we had to lie or the times we stayed silent – we at least experience them, no matter how much pop-psychology clipart we’re subjected to on Facebook.

Even so, there’s a difference between supporting controversial policy and having to own it. Shipley insists her reforms in health and social services as Minister for both were part of a caucus process, an insistence that her tone on the podcast indicates borne more out of defensiveness than modesty. “It’s interesting that people attribute things to an individual. Frankly, that’s ignorant nonsense.”

Of the five subjects, Helen Clark is the only one that’s an enduring and popular political force. Until a couple of weeks ago, she marked the last time the New Zealand Labour Party had a well-liked leader, and the deceptive smoothing effect of time has made the 1990s seem harsh and the 2000s seem pretty beatific. Of any living PM, she’s probably got the most scope and goodwill to acknowledge the mistakes which taint her legacy.

She doesn’t. Clark left office with a growing rate of child poverty (which, to her credit, had temporarily reduced under her watch). Espiner questions her about how the Working For Families package her government introduced excluded what would become a growing number of unemployed and under-employed families, disproportionately from Māori and Pacific Island families, disproportionately likely to be headed by single women, and disproportionately likely to face additional health, housing and transport costs. She blathers: “It had the component of the in-work payment…the problem is that if wages are very low and the cost of transport and being at work makes it no better off, you have to make it better.”

The problems Clark describes – penury wages, transport poverty in the absence of affordable public options – have obvious solutions beyond tax-credit tinkering, and they’ve either been implemented or preserved in places like Australia and Germany. But her Labour government faced a challenging climate that involved disappointing compromise, and now would be a fine a time as any to concede those compromises. Instead, we get “there should be a greater reward for going to work.” End of story.

Giving in to incessant political pressure on her right could also be an explanation (not an excuse) for the passage of the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004. For The Spinoff, Miriama Aoake has already made the case for why virtually any Labour leader would be an improvement on Clark’s very low bar, and rightly identifies that she holds no public regrets about her decisions as leader during that saga.

Worse, Clark perpetuates the same decade-old spin on which her government intervened and legislated away the right for customary landholders to go to court and secure rights: “For me, as a Kiwi, the right to be able to walk along the sea coast is pretty precious…it would’ve been [under threat] had the whole thing played through.” Then, and now, Pākehā and overseas buyers have been able to do the same and restrict that right in piecemeal form, and crowdfunders and councils alike increasingly require huge amounts to secure any public or communal access at all. As with all of her peers, Clark has very little to lose at this stage, and finally acknowledging the weak opportunism of her arguments at the time would have gone some way at no cost.

We see inane rhetoric about regretting nothing, not looking back, and making tough decisions virtually anywhere there’s politicians, or businesspeople. Writing for Aeon in 2013, Carina Chocano described the “disdain for regret” in US culture (and Western culture in general):

“Pop psychology books on the subject of regret offer easy-to-follow plans on how to eradicate it, like a virus or a muffin top…regret isn’t just seen as antithetical to reason, it’s spiritually transgressive as well…For the rationalist, regretting past events or actions is tantamount to admitting the terrifying possibility that failing is as easy as knocking over a glass..

And yet something about these attitudes toward regret rankles me. They strike me not just as inhumanly opposed to emotion, but also as anti-intellectual.”

Chocano's essay articulates the evaluative and therapeutic nature of regret – its power for learning and growth, not mere self-flagellation – beautifully. Though most of us should be so lucky to own and channel our feelings of regret – over our cruelty in relationships, our weakness under peer pressure, the times we weren’t brave, the times we had to lie or the times we stayed silent – we at least experience them, no matter how much pop-psychology clipart we’re subjected to on Facebook.

The argument that political leadership is some sort of life in extremis where such feelings shouldn’t apply doesn’t wash either – partly because it's an error to assume lives spent in power involve extreme circumstances, while grinding poverty somehow doesn’t.

The leaders in The 9th Floor set us a terrible example, a series of excuses and tendentious rationalisations belying their demeanour of plainspoken and secure intellect. Above all, it’s profoundly alienating to experience regret, to try and suppress it or process it every day to ones’ harm or development, only to see those at the top celebrate its lack as a strength.

The argument that political leadership is some sort of life in extremis where such feelings shouldn’t apply doesn’t wash either – partly because it's an error to assume lives spent in power involve extreme circumstances, while grinding poverty somehow doesn’t. And in terms of disassociating from the cost your small and discrete acts do to others – the stroke of a pen, the giving of an order – I think of my friend’s grandfather, who passed away a couple of years ago after a decorated career in the military and then in public service.

Near the end of the Second World War, he captained a New Zealand gunboat which opened fire on and sank an Italian counterpart with some 200 men on board. It was a context where he could go through life without comeuppances, or consequences, or opprobrium, because war is a terrible thing that sets up its own perverse moral codes for when doing harm is okay. Yet in his final years, suddenly encumbered by too much time and too much silence, the vision of the sinking ship ate at him with a renewed intensity, in fitful sleep at night and sudden and teary-eyed daytime reveries. When the veils of circumstance were lifted, he still gave the order that created dozens of Mediterranean graves, and dozens more widows and orphans.

Palmer, Moore, Bolger, Shipley and Clark never held life and death in their hands so explicitly, but the consequences of their actions carry a weight beyond whether or not you, a citizen, agree with the intentions. Indeed, it could be argued that the only acceptable reaction for many modern politicians looking back on their careers should be the same as that of a haunted, ailing old soldier. The human toll of disenfranchisement, dejection, despair, illness, early death, crime, suicide, and choices foreclosed is incalculable – and prevarication on the timing, pointing of the fingers, or Nike slogans about not regretting it are not enough. If we’re so keen as a constituency to assign shamelessness to Turei and see it fit to end her career, we could try applying the same standard to those who actually held government, then decide whether those groups who still fly their pennant today will do any better.

[1] M. Mowbray. “Distributions and Disparity: New Zealand Household Incomes”. Information and Analysis Group, Ministry of Social Policy, 2001, p.13.

[2] J. Kelsey. “Rolling Back The State: Privatisation of Power in Aotearoa/New Zealand”. Bridget Williams Books, 1993, p.331.

[3] Bolger's point could at least be conceded that there has been a long, long time in which to reverse changes and trends which commenced under his watch. Occasional claims, for example, that responsibility for the Pike River Disaster lies with deregulation and deresourcing in the 1990s seem to give the nine years of a Labour government in which the ill-fated mine was approved and developed an awful lot of credit.