Humour and Discomfort: Talking to Yvonne Todd

Charlotte Doyle discovers that no one can talk about Yvonne Todd's work as well as the artist herself.

Charlotte Doyle discovers that no one can talk about Yvonne Todd’s work as well as the artist herself.

Yvonne Todd doesn’t really care if you don’t “get” her photographs. She doesn’t want to educate. Nor is she interested in overt associations. There’ll be no self-indulgent navel gazing, and answers are not guaranteed. She doesn’t want to make “decorative fluff”. What she does want is to entertain.

The renowned photographer confesses to a constant desire for entertainment during a conversation with me at the Peter McLeavey Gallery, above Cuba Street in Wellington. Before our meeting, I overhear her speaking to a group of high school students and write in my notebook that Todd is funny. Hers is a frank, slightly sarcastic humour – “I’ve discovered I’m not a very good employee.”

For a bad employee, she’s had considerable success. In 2002, she won the prestigious Walters Prize with her final works for art school. 2014 saw a major exhibition of her work, Creamy Psychology, mounted at City Gallery Wellington, with over 150 photographs filling the exhibition spaces across the institution’s two floors.

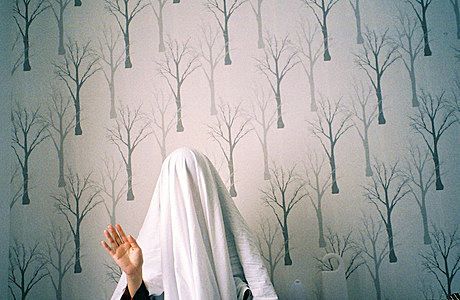

Todd’s work may be intended to have entertainment value, but it doesn’t lack depth. For over 10 years, she’s returned to favourite tropes, producing intimate images of anorexic women, cosmeticians, divas, vegans, and crippled people, often in stiff poses and with extra glossy skin. Wearing unfashionable gowns, unfitting wigs, and unhappy expressions, her awkward, and usually female, characters are surprisingly familiar. They have a disconcerting resonance with our personal lives. Todd tells me that discomfort is as important to her as humour.

I’ve met with the artist to talk about her most recent show, Vermillion, at the Peter McLeavey Gallery. Three portraits of intricately dressed women dominate the walls, but something is different here. Todd’s photographs have never lacked other-worldliness or mystery, yet in this series the fantasy is more explicit. Enskë is inspired by Alice in Wonderland. Morka wears an alien, almost Teletubby-like, purple halo. Maudie is swathed in a bright green cape and sports a bowl cut.

Shown in life size, these women are different to those previously presented by Todd. They are beautiful, with smooth but not waxy skin. Their gazes are strong and composed, not distant or withdrawn. There is a sense that the characters have powerful stories and serious accomplishments. The gallery director, Olivia McLeavey, and I speculate as to whether the shift from pitied to almost pitying women is due to Todd having a baby – surely an ultimate demonstration of female strength.

I talk with the artist about Maudie, whose name literally means “mighty in battle”. I think she looks like a retro Cleopatra. Todd says she thinks of the “dingo got my baby” woman. A green ribbon wrapped around the model’s hand looks almost like boxing tape. Or is there some symbolic ritual of holding ribbons that I’m not aware of? Todd explains that it’s just there because the hands looked awkward. We talk about Australia’s Next Top Model and the judges’ constant feedback on the models’ hands in photographs.

Todd reveals that she likes the “middle” and is drawn to suburbia. She goes to the park with her son and other mums, likes shopping malls. Still living in Takapuna, where she was born and raised, she continues to frequent the local shopping mall that’s nearly the same age as she is. Her work e-Stephanie shows a lamp at the mall, a relic that has survived a number of refurbishments. As a kid, Todd thought the golden lamp was full of orange juice.

Photographing it as an adult with a large film camera, Todd stood surrounded by traffic cones, which protected her as she disappeared under a black cloth. Her methods are entirely analogue. In the past, she sometimes used Photoshop, but the process would drag out and she’d lose interest, so she converted herself into something of a purist. As a result, her “project management” has become more detailed and challenging, the work physically demanding. I ask her if that’s part of the fun. “Fun”, she echoes, in a tone that makes it clear that it’s sometimes no fun at all.

Todd tells me that she wants her photographs to present contemporary cultural landscapes and a history (she hates words like “retro” and “nostalgic”). Many of her previous series have documented social experiments. The Wall of Man from 2009 features stereotypically “prestigious” men: a sales executive, an image consultant, a company founder, a family doctor, an agrichemical spokesman, even a retired urologist (who flaunts hideous tan glasses). The models are in fact suburban men who responded to an ad in the North Shore Times. Todd recalls, “One day three men turned up to my house … Don’t know what the neighbours thought.”

The models, however, are really secondary. Costumes come first, then Todd finds someone to wear them. Like Cindy Sherman, whose famous self-portraits are aesthetically similar to Todd’s images of other people, the commentary lies in whatever she ironically mimics in her photographs. Todd tells me she doesn’t “bulldoze” into strangers so much now, relying more on “accidental netting” when sourcing models.

The final portrait in Vermillion is not a person at all but a basking sea lion. Todd has “collaborated” with her late second cousin, Gilbert Melrose, carefully placing water drops over one of his Matamata camera club photographs of zoo animals. The work sits as a whimsical antidote to Todd’s fantastical portraits, a pinnipedian version of Manet’s Olympia.

Despite the artistic and perhaps personal shift, these images remain distinctively Yvonne Todd. Like her previous photographs, they are challenging. There’s an unwavering shyness and stability that underlies them. Perhaps it’s the perfect combination to create some of New Zealand’s most intriguing imagery.

We end talking about Todd’s first foray into sculpture a number of years ago, a grim doll-sized iron lung displayed on a plinth at the Peter McLeavey Gallery. She knew Peter didn’t like it because it was the only thing he ever sent back, and without a word too. She hasn’t produced any more sculpture since. But of course she’s kept making photographs. I’m glad she has. And glad to have had the chance to talk to her. No one can discuss Todd’s work as well as she can. Anyone else would sound a bit too stuffy.

All images courtesy of the artist and the Peter McLeavey Gallery.