Stifling Silence: A review of Bird Collector

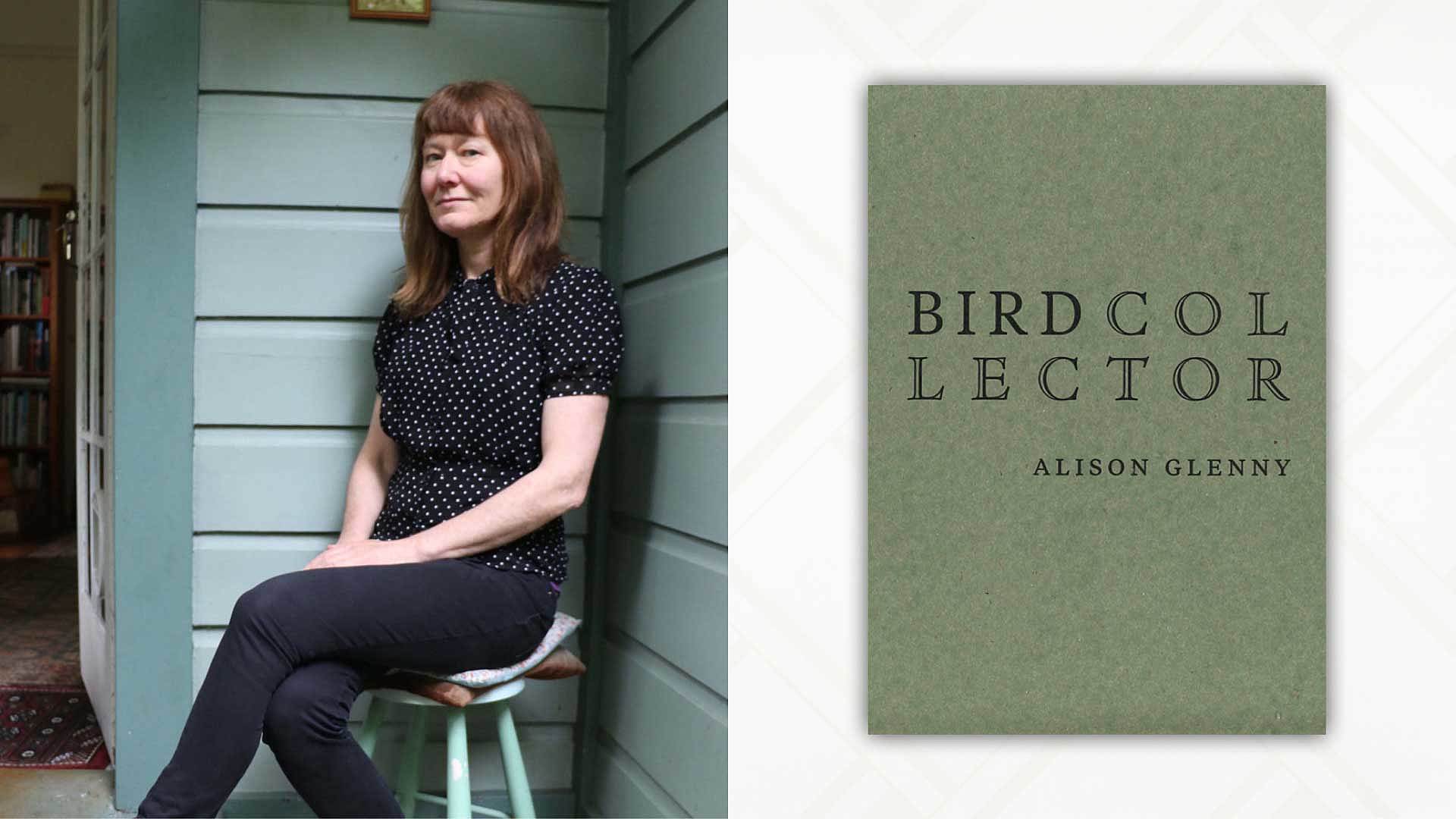

essa may ranapiri on Bird Collector, a poetry collection that liberates form and painfully evokes the silencing of Aotearoa’s forests.

In my response to Alison Glenny’s The Farewell TouristI voiced my excitement to see where Glenny would go next in evoking the unspoken. In Bird Collector, she focuses on the unsung.

Bird Collector is a book split in two, ‘Bird Organ’ and ‘Nights with the Collector’. Each of these sections begins with a straightforward prose poem sequence and then descends into fragments of a sort that seem to reference some since disappeared texts or objects, similar to forms that Glenny utilised in her first book. I often find that conceptual containers for poetry collections allow the form of the work to be liberated; and it’s very much the case in Bird Collector. There are a multitude of forms here.

My favourite of the experiments is ‘The Nineteenth Century Novel: A Glossary Of Terms’, a list of terms with definitions for different garments of clothing which speak to some metaphysical characteristic. This poem twists language and undresses the assumptions we have about meaning;

chemise. The chemistry of an irresistible attraction; likened to

the sensation of being smothered or trussed.

corsage. The passage of desire through a sequence of objects,

viz. bodice, ribbon, gown, dance, night.

crinoline. The waxy heat of candles in a dark room. Associated

with the memory of the death of a beloved pet.

There is something haunting about this book, reflecting on a society that wears the dead. Some of the most sinister lines come from the footnoted sections of ‘Bird Organ’. On one side are prose poems that explore a character in some state of mourning, obsessed with a key, remembering a poem. On the other is a blank space with footnotes at the bottom of the page. They speak to a world around the text:

13 He gave her a feather belonging to a rare New Zealand wattlebird,

and she wore it in her hair. But was this a sign of mourning, and if

so, what had been lost?

14 The use of candles to illuminate the folios makes it necessary

to consider the field of production, also a lingering attachment to

nightingales.

15 If only the long, curved beaks of the females had not resembled

ivory, sparking an immoderate desire for brooches, adorned with

tiny chains. The last pair of laughing owls were sent as a gift to a

collector, and vanished in the darkness of the museum.

For me, this is the painful heart of the book, these footnotes that are orphaned from whatever original text was lost. How birds signify death, and in the process of becoming that aesthetic signifier, are condemned to death itself. We as tāngata whenua got our language from the birds, and we too wore our bird kin on tinana, and sang with them in song. But always a balance. Here in this colonial dream, there is no balance. The death cult of Victorian England tears through our worlds of both flora and fauna.

5 While the custom of wearing the feathers at funerals is said to have

contributed to the bird’s demise, historians note that the sanctuaries

had already been burned.

Glenny paints this image of pain so vividly. The countless lists of animals we have lost, the countless we have yet to lose when facing a diminishing timeline to respond to the climate catastrophe. It is frankly terrifying to be trapped inside the cage of this book. I can feel my ancestors crying; I can hear the birdsong go quiet. What does the bird collector do? What is their role? Do they collect to save? Is the dark of the museum a place we want our ancestors to live in? Or are we pinning our gods to walls to point at?

This book holds many questions and has no claims to answers. There is so much that has been lost. And that is spoken to in Glenny’s generous use of white space. I loved the white space in The Farewell Tourist, and I love it here, what white space does to the brain; frees us from the block of text, and ‘Fragments and Notes’ what seems to be a form of erasure, excels at this. The square brackets around nothing. The delicate lines that remain;

]

]

]

a room

of memories

measured by

[

]

tiny cogs

I can hear the clinking away of these small metal parts as they reverberate across emptiness. In the hollow clang where waiata manu once filled the ngahere there are only cold rooms full of nature put into drawers as dead objects. You can imagine the songs sung stretched across all the gaps that fill this book. The death of birds, the death of the precious taonga o Tāne. It’s this stifling silence that moves through this pukapuka. Where the white pages evoked the white surfaces of Antarctica in The Farewell Tourist, here they push on the silence that colonisation has brought upon the land.

Bird Collector is published by Compound Press.